Digital & Print Membership

Yearly + Receive 8 free printed back issues

$420 Annually

Monthly + Receive 3 free printed back issues

$40 Monthly

The “Modern-Day Columbus”?

Or, What Lies Behind A Bread Culture

If you’re not Mexican, you might’ve missed one of the latest insults aimed at our country. But it hasn’t been long since a renowned British baker decided to comment on Mexico’s lack of bread culture and informed the international community (via podcast, because of course) that he planned to open the “best bakery” in Mexico City—a claim that, in a city grappling with gentrification, isn’t just arrogant; it’s political.

Richard Hart, the baker in question, is now the not-so-proud founder of Green Rhino, which opened in the widely gentrified Roma Norte neighbourhood of Mexico City back in June of last year. Hearing Hart’s entire tirade against the “ugly”, “cheap”, “completely highly processed”, and “industrially-made” bread we Mexicans eat, you might be tempted to take his expert opinion at face value and think nothing more of it. But beyond the rudeness of his commentary, there lies an insidious cultural delegitimisation that paves the way for invisibilising the produce of his host country and attempting to replace its “better” version.

In reality, what lies behind Mexico’s “non-existent” bread culture is a rich tradition that has learned and thrived from adversity—from the conquest period, when European ingredients like wheat were introduced into the land by way of a violent colonisation that killed thousands of natives and effectively disappeared a number of their customs, to this day.

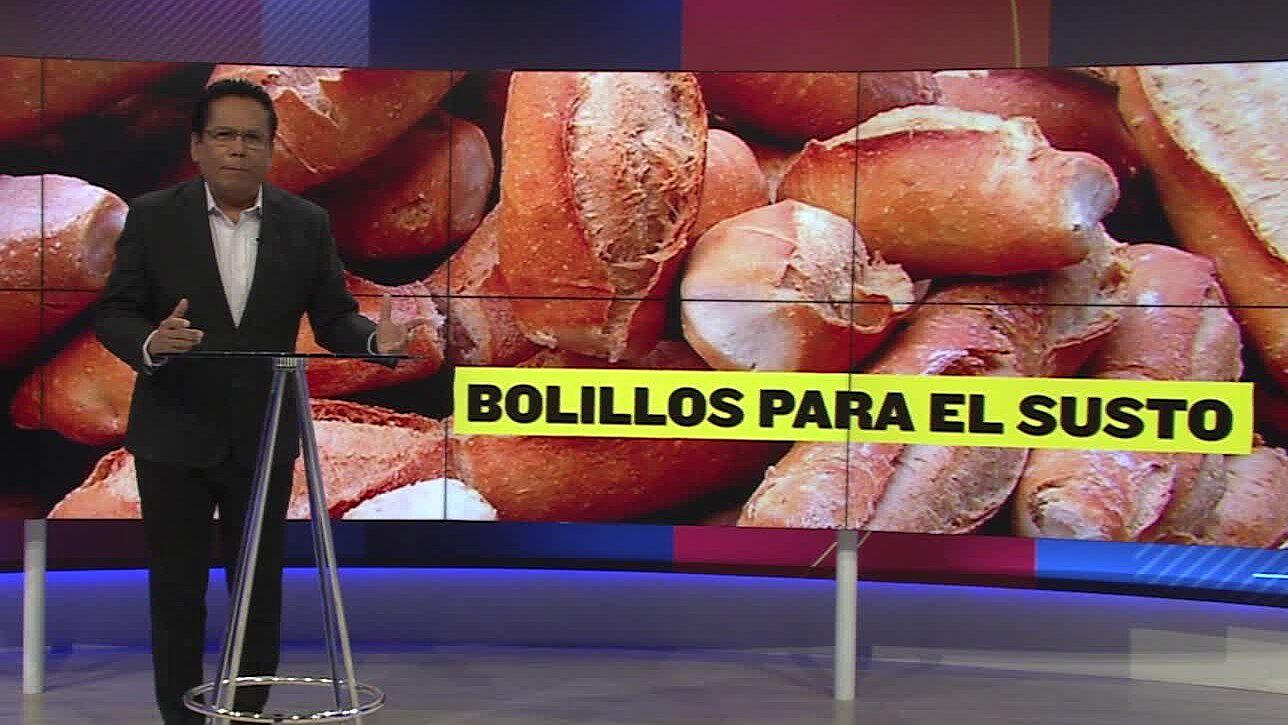

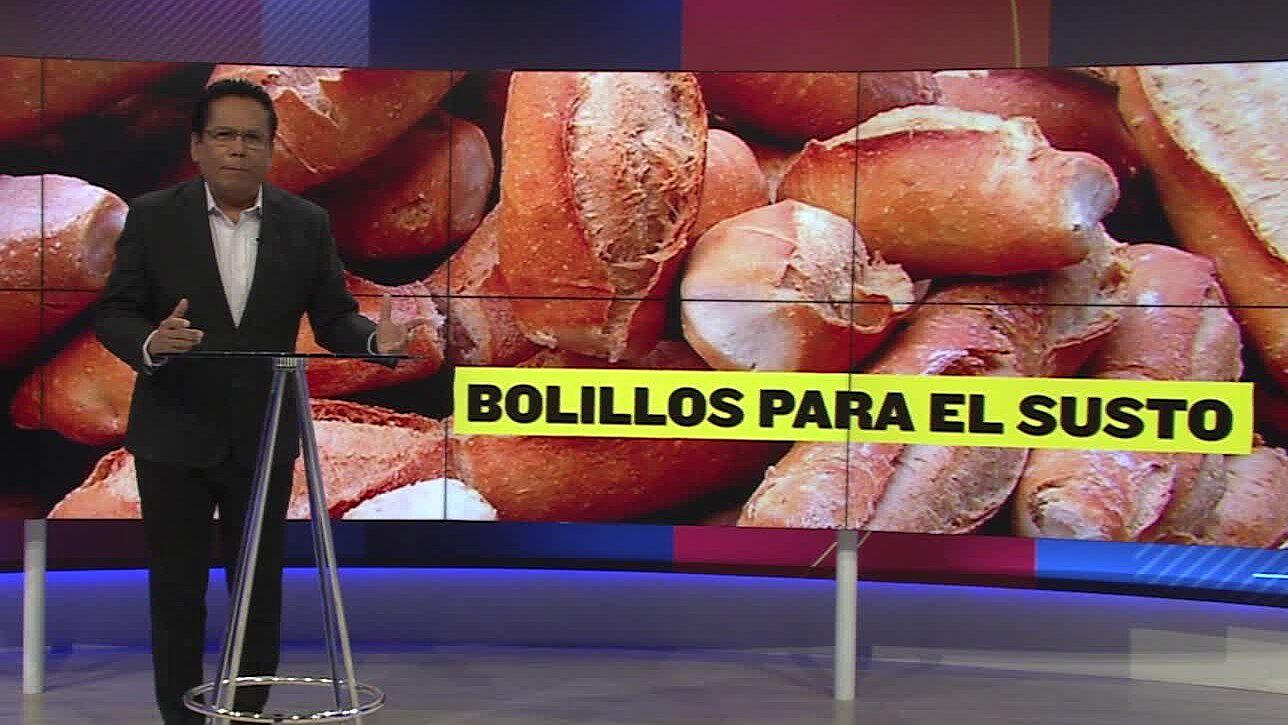

Take the bolillo, the main subject of Hart’s harsh criticism, for example. While he dismissed it as a “white ugly” roll, the bolillo has become a staple in Mexican cuisine. And it wasn’t because it was perfect according to European techniques or because its preparation relied on the highest quality ingredients, but rather quite the opposite. The bolillo was made to sustain the masses, the mostly poor, rural population that comprised most of Mexico’s inhabitants until relatively recently in the country’s history. Thus, Mexican bakers made the most of the affordable ingredients within reach to feed the population.

Today, the humble bolillo knows of no social class and is enjoyed by rich or poor alike.

It is so much a part of our culture that it is used as a home remedy for bad frights, or sustos, believed to cause a number of maladies according to popular wisdom, from paralysis to diabetes. This belief is so ingrained in Mexican thought that bolillo sales in Mexico City go up after one of its all-too-common, but no less frightening, earthquakes.

Pan de muerto (bread of the dead) is yet another example of how deeply ingrained bread is in Mexican culture. This beloved item is central to Day of the Dead celebrations, whose origin can be traced back to pre-Hispanic times. Its mere existence is a testament to the natives’ resilience in the face of genocide and religious suppression. Its elaboration, despite what Hart would have us believe, is far from being cheap or simple. There are, in fact, 12 different varieties, each differing widely in terms of ingredients and preparation. The latter is also far from being a purely industrialised process, as many families and communities still come together to make it at home the traditional way each year, despite it being readily available everywhere—from small neighbourhood bakeries to big supermarket chains.

Nowadays, with gentrification (the process in which wealthier newcomers displace the local population of cities) being a very real issue affecting Mexico’s major cities, Hart’s comments are not to be taken lightly in view of his bakery’s recent opening in the heart of Mexico City. Rather, it begs the question as to whether Mexicans should be expected to finance a foreign business built on disrespect for local tradition, all while local businesses are driven out of the up-and-coming hubs?

And what does he mean when he says his will be “the best bakery in town?

Does “the best” simply mean more European? And is this just another form, or at the very least a remnant, of colonisation?

Going back to Richard Hart’s main statement, who determines what counts as bread culture or not? As we should know better by now, a culture is a culture, whether someone at the (white European) centre says it’s good or bad, cheap or not. Further yet, if we go deeper into this last point, we might discover that most world cuisines, even those considered more refined and superior, were born out of the creative utilisation of rather undesirable ingredients, as these were simply fairly accessible to a wider population and prone to more creative approaches to make them not only edible but palatable.

And far from being simple, the shortage of high-quality, and hence more expensive, flour in Mexico is a rather complex economic and political issue that can be traced back to the country’s changing agricultural policies and its commercial agreements with other foreign nations. For example, Mexico is nowadays the main importer of basic grains from the US, much to the chagrin of local producers. This comes as a direct result of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA, now replaced by the USMCA), owing to which Mexico is forced to import up to 80% of its wheat—the main ingredient in bread— from its neighbour to the north. According to experts in the field, this puts the country’s agricultural sovereignty at risk to the detriment of local producers and the national economy at large.

Notwithstanding all of the above, Mexicans have continued to thrive with what they have at hand, from the earliest years of the colonisation of the Americas to the full implementation of NAFTA. Overall, Mexico has adopted, adapted, and fully developed multiple varieties of bread throughout its relatively short existence as an independent country. Nowadays, the different types of bread are counted by the thousands. According to national studies, there were 60,000 bakeries spread across the country by 2023, 97% of which were small, mostly family-owned businesses.

Despite being marked by resilience, austerity, and scarcity for perhaps most of its history, Mexico’s bread culture is very much alive. IT exists not only in the panaderias and inside people’s home, but in songs, movies, video games, you name it. Trying to invisibilise it or flat-out deny its existence with little to no context only perpetuates a dangerous trend: that of upholding white European standards as superior, as the norm, as the ultimate goal.

{

"article":

{

"title" : "The “Modern-Day Columbus”? Or, What Lies Behind A Bread Culture",

"author" : "Paulina Odeth Flores Bañuelos",

"category" : "essays",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/the-modern-day-columbus",

"date" : "2026-01-23 08:39:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/El-Cid-Resort---mexicodesconocido.com.mx-d08814.jpg",

"excerpt" : "If you’re not Mexican, you might’ve missed one of the latest insults aimed at our country. But it hasn’t been long since a renowned British baker decided to comment on Mexico’s lack of bread culture and informed the international community (via podcast, because of course) that he planned to open the “best bakery” in Mexico City—a claim that, in a city grappling with gentrification, isn’t just arrogant; it’s political.",

"content" : "If you’re not Mexican, you might’ve missed one of the latest insults aimed at our country. But it hasn’t been long since a renowned British baker decided to comment on Mexico’s lack of bread culture and informed the international community (via podcast, because of course) that he planned to open the “best bakery” in Mexico City—a claim that, in a city grappling with gentrification, isn’t just arrogant; it’s political. Richard Hart, the baker in question, is now the not-so-proud founder of Green Rhino, which opened in the widely gentrified Roma Norte neighbourhood of Mexico City back in June of last year. Hearing Hart’s entire tirade against the “ugly”, “cheap”, “completely highly processed”, and “industrially-made” bread we Mexicans eat, you might be tempted to take his expert opinion at face value and think nothing more of it. But beyond the rudeness of his commentary, there lies an insidious cultural delegitimisation that paves the way for invisibilising the produce of his host country and attempting to replace its “better” version. In reality, what lies behind Mexico’s “non-existent” bread culture is a rich tradition that has learned and thrived from adversity—from the conquest period, when European ingredients like wheat were introduced into the land by way of a violent colonisation that killed thousands of natives and effectively disappeared a number of their customs, to this day. Take the bolillo, the main subject of Hart’s harsh criticism, for example. While he dismissed it as a “white ugly” roll, the bolillo has become a staple in Mexican cuisine. And it wasn’t because it was perfect according to European techniques or because its preparation relied on the highest quality ingredients, but rather quite the opposite. The bolillo was made to sustain the masses, the mostly poor, rural population that comprised most of Mexico’s inhabitants until relatively recently in the country’s history. Thus, Mexican bakers made the most of the affordable ingredients within reach to feed the population. Today, the humble bolillo knows of no social class and is enjoyed by rich or poor alike. It is so much a part of our culture that it is used as a home remedy for bad frights, or sustos, believed to cause a number of maladies according to popular wisdom, from paralysis to diabetes. This belief is so ingrained in Mexican thought that bolillo sales in Mexico City go up after one of its all-too-common, but no less frightening, earthquakes. Pan de muerto (bread of the dead) is yet another example of how deeply ingrained bread is in Mexican culture. This beloved item is central to Day of the Dead celebrations, whose origin can be traced back to pre-Hispanic times. Its mere existence is a testament to the natives’ resilience in the face of genocide and religious suppression. Its elaboration, despite what Hart would have us believe, is far from being cheap or simple. There are, in fact, 12 different varieties, each differing widely in terms of ingredients and preparation. The latter is also far from being a purely industrialised process, as many families and communities still come together to make it at home the traditional way each year, despite it being readily available everywhere—from small neighbourhood bakeries to big supermarket chains. Nowadays, with gentrification (the process in which wealthier newcomers displace the local population of cities) being a very real issue affecting Mexico’s major cities, Hart’s comments are not to be taken lightly in view of his bakery’s recent opening in the heart of Mexico City. Rather, it begs the question as to whether Mexicans should be expected to finance a foreign business built on disrespect for local tradition, all while local businesses are driven out of the up-and-coming hubs?And what does he mean when he says his will be “the best bakery in town? Does “the best” simply mean more European? And is this just another form, or at the very least a remnant, of colonisation?Going back to Richard Hart’s main statement, who determines what counts as bread culture or not? As we should know better by now, a culture is a culture, whether someone at the (white European) centre says it’s good or bad, cheap or not. Further yet, if we go deeper into this last point, we might discover that most world cuisines, even those considered more refined and superior, were born out of the creative utilisation of rather undesirable ingredients, as these were simply fairly accessible to a wider population and prone to more creative approaches to make them not only edible but palatable. And far from being simple, the shortage of high-quality, and hence more expensive, flour in Mexico is a rather complex economic and political issue that can be traced back to the country’s changing agricultural policies and its commercial agreements with other foreign nations. For example, Mexico is nowadays the main importer of basic grains from the US, much to the chagrin of local producers. This comes as a direct result of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA, now replaced by the USMCA), owing to which Mexico is forced to import up to 80% of its wheat—the main ingredient in bread— from its neighbour to the north. According to experts in the field, this puts the country’s agricultural sovereignty at risk to the detriment of local producers and the national economy at large. Notwithstanding all of the above, Mexicans have continued to thrive with what they have at hand, from the earliest years of the colonisation of the Americas to the full implementation of NAFTA. Overall, Mexico has adopted, adapted, and fully developed multiple varieties of bread throughout its relatively short existence as an independent country. Nowadays, the different types of bread are counted by the thousands. According to national studies, there were 60,000 bakeries spread across the country by 2023, 97% of which were small, mostly family-owned businesses. Despite being marked by resilience, austerity, and scarcity for perhaps most of its history, Mexico’s bread culture is very much alive. IT exists not only in the panaderias and inside people’s home, but in songs, movies, video games, you name it. Trying to invisibilise it or flat-out deny its existence with little to no context only perpetuates a dangerous trend: that of upholding white European standards as superior, as the norm, as the ultimate goal. "

}

,

"relatedposts": [

{

"title" : "Weaving Palestinian Heritage with Lara Salous’ Wool Woman",

"author" : "Ayesha Le Breton",

"category" : "interviews",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/lara-salous-wool-woman-palestine-heritage-interview",

"date" : "2026-03-12 12:21:00 -0400",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/Wool%20Woman%20Image%201.jpeg",

"excerpt" : "",

"content" : "Lara Salous with shepherd Rajeh Al-Essa at his house in Mughayer village where he shows her how to use the Palestinian traditional drop spindle (Ghazzale)Photo Credit: Raof Haj YahyaTo Lara Salous, the disappearing art of wool weaving needs a revival. “The loom is a tool that’s now endangered in Palestine,” says the 37-year-old Palestinian artist and designer, who called me from her studio, nestled in Ramallah Al-balad, the old city, in the occupied West Bank. She’d spent the morning packing art frames, throws, and short stools that customers in Norway and Canada ordered from her home decor brand: Wool Woman. “It’s more of a network rather than a company that controls everything,” Salous explains of Wool Woman. Behind the brand is a delicate, sometimes precarious, web that connects Salous to shepherds and wool spinners in Palestine—too often at the mercy of Israel’s siege of the area. Abu Saddam Traifat, a Palestinian Bedouin shepherd who Salous sourced her wool from, for instance, spent years tending to his Indigenous flock of Awassi sheep in al-Auja, Jericho, washing his harvest of wool in the vital water spring. All his sheep are now gone, as are the majority of Palestinians in the area, because Israeli settlers, accompanied by the Israeli army and police, stole all his sheep in the middle of the night. This, Salous explains, is just one case of how Israeli control and violence affect the area. “In al-Mughayer, a village near Ramallah, I interviewed three shepherds,” she says. “When I visited them the last time, it was just after the settlers burned 30 houses, including one of the shepherd’s homes. ”Recent reports by Al Jazeera confirm that Israeli settlers have annexed the entirety of al-Auja spring, forcing out and blocking water access to Bedouin herding communities like Traifat’s, who have resided in the surrounding areas since before 1967. Throughout 2025, settler violence against Palestinians soared to record devastation across the West Bank. In October alone, there were over 260 violent attacks, leading to deaths, injuries, property damage, and stolen livestock. As Israel’s genocide on Gaza and occupied Palestine rages on, Salous’s Wool Woman feels more crucial than ever to archive and celebrate Palestinian culture and identity. Lara embroidering the Palestinian flag with wool on a woven frame. Photo Credit: Mahmoud AbdatSalous traces Wool Woman’s inspiration back to October 2020. At the time, she was teaching an architecture and design course at her alma mater, Birzeit University, near Ramallah, and participating in a workshop investigating historical, cultural, and personal ties to the making of Palestinian rugs. It was on a field trip to visit Bedouin communities in Khan al-Ahmar, whose rug industry was once integral to the area’s economic livelihood, that Salous was struck by the absence of rugs and the wool used to make them. She learned that shortly after Al Naqba, the tribe fled harassment in the hills south of Hebron, leaving their homes and belongings, including the livestock and wool. But even in their new location, Israel encroached upon the Bedouin community’s lives, limiting where they could graze and raise their sheep, eventually making wool production nearly impossible. “Something started to spark in my mind; I began questioning what was happening to this industry or to this craft,” Salous remembers. “The [Bedouin women] showed us one [rug] that they preserved in a wooden box, which is used for celebrations or weddings. ” I asked them, “Why don’t you make them anymore? They said, ‘It’s so hard to maintain a living from sheep because we are in a daily struggle with the Israeli settlers. ’”Houses in Khan al Ahmar where Lara visits the woman she purchases wool from. Photo Credit: Lara SalousWitnessing remnants of the fading practice, Salous felt a renewed sense of purpose in working with these artisans. Through word of mouth and returning to Bedouin communities in Khan al-Ahmar, Salous began interviewing, photographing, and filming the shepherds, descendants of weavers, and searching for wool spinners. “I’m collecting oral history and trying to capture images and short videos, because you can never find anything in the archives,” Salous explains. “We invited one woman to weave at the university. I then started to ask around about women who are still spinning [wool]. It took me a lot of time, to be honest. ” Years of field research and building relationships culminated in the evolving network that now makes Wool Woman possible. Using her interior design background, Salous started to integrate wool into furniture designs. Since most Bedouin weavers are either displaced or long deceased, she is mostly self-taught and dyes the material herself. Experimentation and play are at the center of her process. She conjures thoughtful motifs of Palestinian identity and liberation, including olive trees, poppies, and watermelon slices. She incorporates bold teal and maroon stripes and abstract color blocking that take shape on rocking chairs, room dividers, throws, curtains, and benches, among other pieces. “Sometimes I do some design sketches on paper, [or] I just design on the spot while mixing the colors because you can do more when you have these rich textures and tones in your hand,” explains Salous. The first products she sold were stools and chairs created with carpenters in Ramallah—the carpenters crafted the wooden structures while Salous wove the seats and backs. LEFT: Lara’s woven olive tree design on a stool inspired by the Palestinian landscape. Photo Credit: Lara SalousRIGHT: Lara finalizing a wool throw she wove on the loom. Photo Credit: Mahmoud Abdat“The kick start for me was at a gallery here called Living Cultures, but now it’s closed. People started to come, and they purchased them [the stools and chairs],” she recalls. “From there, I built on other designs. It was very interactive with the local community because people started to ask me for bigger chairs or higher stools or chairs with a big back. ”Community is core to the designer’s craft revival. “It’s something that we inherited, and we need to pass it from hand to hand,” Salous explains. Through Wool Woman and the Palestinian Centre for Architectural Conservation, Salous has developed intergenerational weaving workshops for children and their parents, and any adults who wish to participate. Together, they create natural dyes with flower petals and integrate Palestinian traditional tile design into simple weavings. Her impact on attendees extends far beyond the triannual sessions. Salous beams when she explains that some students have taken on the practice as their own. “I’m so happy that one of the students purchased a professional loom that she now has at home. Another one who was very excited; he wanted to work with me,” she says. Running Wool Woman is not without its challenges. As the shepherds and women Salous sources from remain under constant threat of theft, violence, and land siege—their livelihoods at stake—Wool Woman has encountered supply chain delays and Salous has had to pause visits to her collaborators’ communities. “It’s not safe at all,” she shares. “I keep sourcing from one shepherd, but it’s very dangerous now, especially recently, now that the Israeli settlers built another settlement on the top of their mountain [in al-Mughayer]. ” She keeps up with orders as best she can, holding onto a stock of wool that is already processed and spun, and dyeing the material herself. “To be honest, it’s exhausting,” she admits. Local demand has expectedly dwindled throughout the genocide, making it impossible for Wool Woman to afford employees and increasingly difficult to make a profit. But as Salous recounts these hardships with vulnerability, her commitment to preserving Palestinian weaving echoes. “I’m alone on the business side, but I keep supporting these women by purchasing wool from them,” she says. “[I’m] trying to take this material into other shapes and other possibilities. ”Lately, Wool Woman has found creative refuge by collaborating with fellow Palestinian artists. “With architects, interior designers, and fashion designers, these are the best projects I ever had because you feel that you are integrating more into your community,” shares Salous. Nöl Collective, the popular fashion label that celebrates weavers and embroiderers across Palestine, recently commissioned braiding from Wool Woman for a pair of trousers. And it was through their founder that Salous connected with Hussam Zaqout, one of the last surviving Gazan weavers and the inspiration for her latest art installation, If Only We Could Bury Our City. Guided by their shared purpose of preserving Palestinian heritage, Salous presents a towering traditional Majdalwi Fabric loom and intimate interviews with Zaqout, who narrates his intergenerational connection to the ancient profession. Multimedia installation of ‘If Only We Could Bury Our City,’ made from Lara’s research and interviews with Hussam Zaqout. Photo Credit: Elis HannikainenFor Zaqout, Israel’s genocidal onslaught is tangible. “Just one month before the war, I had set up a new workshop, added additional tools and equipment to expand my work. I also had parts of a weaving loom that existed in the city of al-Majdal before the occupation,” he recalls. “Unfortunately, all of this was destroyed during the airstrikes on the city. ” By March 2024, Zaqout made the difficult and expensive decision to evacuate Gaza to Cairo. Through fundraising, he and some of his family reached Cairo safely, where he has been rebuilding his weaving center. Facing profound loss and a need for hope, for Zaqout, contributing to Salous’s art felt imperative. He shares, “It was a mix of pride, gratitude, and responsibility: for my personal experience and the craft I inherited from my father, to be an inspiration for an artwork of this significance. [It] makes me feel that the voice of my family, the voice of Palestine, and the memory of my hometown, al-Majdal, are still present and not forgotten, despite all the loss and displacement we have endured. ”In the wake of destruction, clinging to and sharing memories has become a form of resistance and a means of survival. Salous delicately entwines oral histories, like Zaqout’s, and material politics into thoughtful art and design, holding a rare space for Palestinian identity, culture, and history to flourish. “One story could say a lot about [the] shared realities that Palestinians face since the Nakba. Through meeting Husam and other Palestinian weavers, I bring back memories to a wider audience,” says Salous. “Our cities are being erased, but we still hold them in our bodies and memories. ”Multimedia installation of ‘If Only We Could Bury Our City,’ made from Lara’s research and interviews with Hussam Zaqout. Photo Credit: Elis Hannikainen"

}

,

{

"title" : "Forced From Home: Women Living Through Lebanon’s Evacuation Zones",

"author" : "Sarah Sinno",

"category" : "essay",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/forced-from-home",

"date" : "2026-03-12 11:56:00 -0400",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/PHOTO-2026-03-11-04-23-35.jpg",

"excerpt" : "",

"content" : "Photo Credit: Omar GabrielMalak told me they left Chaqra, a village in southern Lebanon, at four in the morning and did not reach her aunt’s house in Saida until one in the morning the next day. “We were fasting and exhausted, but we had dates,” she said. “We took them out of the car and began sharing them with the people around us. We also helped another repair a car that had broken down, and despite the fear, we got to know each other. ”The following morning, the news arrived: their house had been bombed by Israel. On March 2, residents across southern Lebanon woke to Israeli “evacuation orders. ” At first glance, the term suggests concern for civilian life, invoking the language of safety and protection. In reality, however, these orders function as a mechanism of forced uprooting, compelling entire communities to abandon their homes under the threat of bombardment. Official state reports indicate that nearly 700,000 people have been internally displaced over the past week. Many spent nearly 24 hours trapped on the roads trying to reach Beirut, a journey that normally takes less than two hours from even the farthest villages along the Lebanese–Palestinian border. Many of those forced to flee their homes had been preparing shour, the meal eaten before sunrise, ahead of the daily fast, when they left in haste, unsure when they would be able to return. Women, who often manage the household, cook, and care for the children, frequently bear the emotional burden of holding the family together in times of crisis while coping with prolonged uncertainty. For working women, displacement frequently results in losing their jobs and the financial independence they once had, pushing them into increasingly difficult conditions to sustain themselves. Photo Credit: Omar GabrielFor instance, on March 4, similar evacuation orders were issued for Dahiye, Beirut’s southern suburbs. Khadije, a resident of Hay Al-Solom, is now sheltering on the second floor of the Lebanese University in Beirut. The public campus, usually crowded with students moving between classes, is now filled with displaced families. “No one has asked about us,” she says. “I am a Lebanese citizen. I have a Lebanese ID. Where is the emergency relief?” Sitting in the corner of a classroom, she speaks with visible disappointment. As she shows me the medicines she depends on, she questions why the Lebanese government has done nothing to provide protection or assistance. It is a sentiment widely shared across a community that has long felt neglected by the state. Even international organizations, faced with shrinking budgets, have fallen short in their relief response and have not been able to act at the level of urgency required. “Several of my neighbors could not leave despite the evacuation order, because they have nowhere to go. They only leave at night and sleep by the beach in Ramlet al-Bayda to escape the constant bombing sounds. ” With no alternative, one might think that sleeping in the open air would, grimly, feel safer than staying in one’s own home. Yet even there, they remain targets of Israeli barbarism. On March 12, around two in the morning, Israel carried out a massacre against displaced people who had sought refuge by the Ramlet al-Bayda beach, killing ten of them. Witnesses describe women’s and children’s body parts scattered across the site. Nowhere is truly safe. Souad, who lives on the outskirts of Beirut, was forced to flee her home and is now sheltering in a school in Choueifat. In this area, speaking with displaced residents proved difficult, as the municipality appears to have imposed strict regulations. These measures are meant to organize the large influx of people and, I was told, prevent chaos. But they also create an uneasy atmosphere. Conversations feel monitored, almost scripted, as if everyone is careful not to say the wrong thing. The tension of this is palpable across the country, with fearmongering on the rise and some openly expressing that they do not want displaced families in their neighborhoods. As a result, many of the displaced feel targeted both by Israel and from within. There is growing concern that even minor disagreements could quickly spiral out of control. With a smile that never quite leaves her face and a frail cat sitting beside us, Souad tells me that her house was destroyed during the previous war. Now, she says, it feels as though everything is happening all over again. “When I lost my house last time, I went back to search through the rubble,” she recalls. “Luckily, I found what is most precious: a photo album of my children. ”Displacement did not begin with the most recent evacuation orders; it has been ongoing. Since 2024, several frontline villages have been razed to the ground and turned into ghost towns. Photo Credit: Omar GabrielReturn has effectively been forbidden as the Israeli occupation gradually expands its control. On March 5, it announced the seizure of additional land alongside the five positions it has held there since November 2024, further entrenching a reality in which many displaced families still have no clear path home. Wafaa, from Rab El Thalathine, a southern village directly on the border, had her home destroyed in 2024 and has not been able to return since. Displaced once again from a second house she had rented in Beirut, she now finds herself sheltering in a school in Burj Abi Haidar. When I ask her what she longs for most once the war is over, a moment of silence follows. She takes a long breath, her voice breaking, and says:“I had planted my garden in the village with all kinds of flowers: jasmine, Damask roses, gardenias, and carnations. After the last so-called ‘ceasefire,’ I was told the garden had been scorched. All I want is for my land to remain. ”As I write these lines, Israel issues new evacuation orders. It never stops. "

}

,

{

"title" : "Mark Zuckerberg Went to the Prada Show In Milan. It Wasn’t For Fashion",

"author" : "Louis Pisano",

"category" : "essay",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/mark-zuckerberg-prada-meta-glasses",

"date" : "2026-03-06 09:07:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/Pisano_Meta_glasses.jpeg",

"excerpt" : "When Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan took their seats in the front row at Prada’s Milan runway show on February 26, the photographs circulated quickly—the Meta CEO in his now-familiar uniform of expensive basics, watching models move down the runway in Miuccia Prada and Raf Simons’ latest vision of intellectual austerity.",

"content" : "When Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan took their seats in the front row at Prada’s Milan runway show on February 26, the photographs circulated quickly—the Meta CEO in his now-familiar uniform of expensive basics, watching models move down the runway in Miuccia Prada and Raf Simons’ latest vision of intellectual austerity. He was there because Meta is in active discussions with Prada to develop a line of branded AI smart glasses, a logical next step for a company whose Ray-Ban partnership has become one of the more surprising consumer electronics stories of the decade. Sales more than tripled in 2025, and on Meta’s January earnings call, Zuckerberg described them as “some of the fastest-growing consumer electronics in history. ” The Oakley deal followed. Prada, if negotiations close, would be the latest luxury house recruited to solve a stubborn distribution problem: how to get people to wear a computer on their face without making them feel like they’re wearing a computer on their face. The answer, apparently, is to put it in a frame that costs as much as a car payment. The Meta Oakley Vanguards can be yours for the low cost of $549. Zuckerberg is not executing this pivot alone. Over the past year, tech’s richest men have staged a quiet, coordinated rebrand away from the founder-in-a-hoodie archetype toward something more deliberately cultured. Jeff Bezos has become a fixture in the fashion press, his aesthetic transformation carefully managed, his public image now signaling cultural seriousness alongside the financial kind. The underlying message from both men is consistent: that they are not the problem, but rather represent the future. And that the future can be beautiful and luxurious. This is what elite legitimacy looks like in our era of late-stage capitalism. When your industry faces sustained scrutiny across antitrust proceedings, data privacy legislation, and the slow erosion of public trust, you don’t just deploy lobbyists and communications teams. You acquire taste. You sit front row at shows with a century of cultural prestige behind them. You let the associations do work that no PR campaign could. Cultural capital operates differently from paid media; it feels earned, and its effects are harder to trace. Which is why the timing of Zuckerberg’s Milan appearance is worth examining more closely. At the same time that Zuckerberg was cementing a potential partnership with one of fashion’s most storied feminist houses, his company’s flagship wearable product was generating very different press coverage. In January 2026, BBC News investigated a pattern of male content creators using Ray-Ban Meta glasses to secretly film women during staged pickup encounters on the street, then uploading the footage to TikTok and Instagram as dating advice content. Dilara, a 21-year-old from London filmed on her lunch break, found her phone number visible in footage that had accumulated 1. 3 million views, leading to a night of abusive calls and messages. Kim, a 56-year-old filmed on a beach in West Sussex, received thousands of inappropriate messages after her video reached 6. 9 million views, and was still receiving them six months later. None of the women had seen any recording indicator. The BBC separately found YouTube tutorials demonstrating how to cover or disable the small LED light that Meta claims signals when the glasses are filming. The problem has spread internationally. In early 2026, a Russian vlogger traveled through Ghana and Kenya filming covert encounters with women using smart glasses (though it has not been confirmed that they were Meta-brand glasses) and posting footage to TikTok, YouTube, and a private Telegram channel where more explicit content was available by paid subscription. Some women were filmed in intimate situations without any knowledge that they were being recorded, let alone distributed to a global audience. Ghana’s Gender Minister confirmed that some victims were receiving psychological support, noting that exposure of this kind carries severe social consequences in conservative communities. Kenya’s Gender Minister called it a serious case of gender-based violence. Meta’s response, when asked for comment, was to point to the LED indicator light and its terms of service, a response that privacy advocates have consistently noted is equivalent to putting a “do not steal” sign on an unlocked car. Hundreds of similar accounts exist across TikTok alone, and the women who appear in them have had no recourse beyond reporting content that has already been viewed millions of times. These cases sit alongside The New York Times’ recent revelation of internal Meta plans for a feature called “Name Tag,” which would allow wearers to identify strangers in real-time by pulling data from Meta’s ecosystem of Instagram and Facebook profiles. Refuge and Women’s Aid told The Independent that this capability would pose a direct and serious risk to domestic abuse survivors, women who have rebuilt their lives at new addresses, hoping that distance and anonymity might be enough. Refuge reported a 62%rise in referrals to its technology-facilitated abuse specialist team in 2025, driven in part by wearable tech being used by abusers to monitor and control partners. Real-time facial recognition running on glasses indistinguishable from any other pair does not care about restraining orders. Into this landscape walks a potential Prada co-branded version of the same device. And there is something worth sitting with in the specific choice of Prada as Meta’s luxury target. Miuccia Prada has spent decades articulating, through her collections and in her public statements, a sustained engagement with feminist thought, grappling explicitly with how women are perceived, constrained, and resist the codes that govern their visibility in public and private life. The Prada woman, as a cultural figure, has never been decorative, according to Miuccia. She is thinking—and she is often acutely aware of being watched. Whether Miuccia Prada or the Prada Group’s leadership has genuinely reckoned with what women’s safety advocates have documented about the device they are being asked to co-brand is a question the company has not yet been asked loudly enough to their consumers. A Prada-branded pair of AI glasses would not simply be a licensing deal; it would be an aesthetic endorsement of the technology inside the frame, lending the cultural authority of a house that has built its identity around the intelligence and autonomy of women to Meta’s surveillance hardware. There is a term for what happens when corporations facing public scrutiny attach themselves to respected cultural institutions, when they fund museum wings, sponsor literary prizes, or plant themselves in the front rows of fashion weeks historically associated with progressive values. The association is meant to transfer accountability and even responsibility. The institution’s credibility flows toward the brand, and the brand’s controversies recede into the background noise of cultural life. Zuckerberg’s Milan appearance fits this pattern. A Prada partnership would give Meta’s smart glasses access to a female luxury consumer demographic they have struggled to reach, while simultaneously borrowing the feminist credibility of a house that has spent decades earning it, at the exact moment when critics, charities, and regulators are arguing most loudly that the product threatens women’s safety. The front row seat was not incidental to the pitch. It was the pitch. But the women who have had their faces filmed without consent, their phone numbers exposed to millions of strangers, their locations potentially traceable by the men who mean them harm, don’t get to sit front row or get a rebrand. What they get is a company whose products have been repeatedly documented and enabled their harassment, now aligning itself with a symbol of female empowerment, hoping the association does its work before the reckoning catches up. Miuccia Prada has built her career on the argument that what we put on our bodies makes an argument about the world. If she signs off on this, the argument she’ll be making won’t be the one she intended. "

}

]

}