Digital & Print Membership

Yearly + Receive 8 free printed back issues

$420 Annually

Monthly + Receive 3 free printed back issues

$40 Monthly

Scholasticide in Gaza

On the Systematic Destruction of Palestinian Education

Gaza graduated its students in mid-November. In caps and gowns, students walked through the ruins, holding diplomas for an education they fought with their lives to keep alive. This is what resistance looks like when a society is being targeted for erasure.

What Israel’s assault sought to destroy, the more than 97 percent of schools damaged or destroyed and all twelve universities reduced to rubble—Palestinians are rebuilding with their hands, their voices, and their refusal to simply disappear. Human rights experts raised the alarm back in April 2024, warning that Israel’s pattern of attacks on schools, universities, teachers, and students constitutes the intentional obliteration of the Palestinian education system. The term for this deliberate destruction of educational infrastructure is scholasticide: the systematic annihilation of education, the targeting of knowledge itself, of the capacity for a people to transmit their history and culture, and hence, their future. But Gaza, with one of the highest literacy rates in the world (97.7%), is answering erasure with something Israel cannot destroy with bombs: knowledge.

The pursuit of knowledge has always been woven into the fabric of Palestinian identity, a form of resistance in itself, a way of asserting presence and possibility in the face of occupation and siege. Many Palestinians, including us in the diaspora, believe everything in life could be taken from us, all except for our education and knowledge.

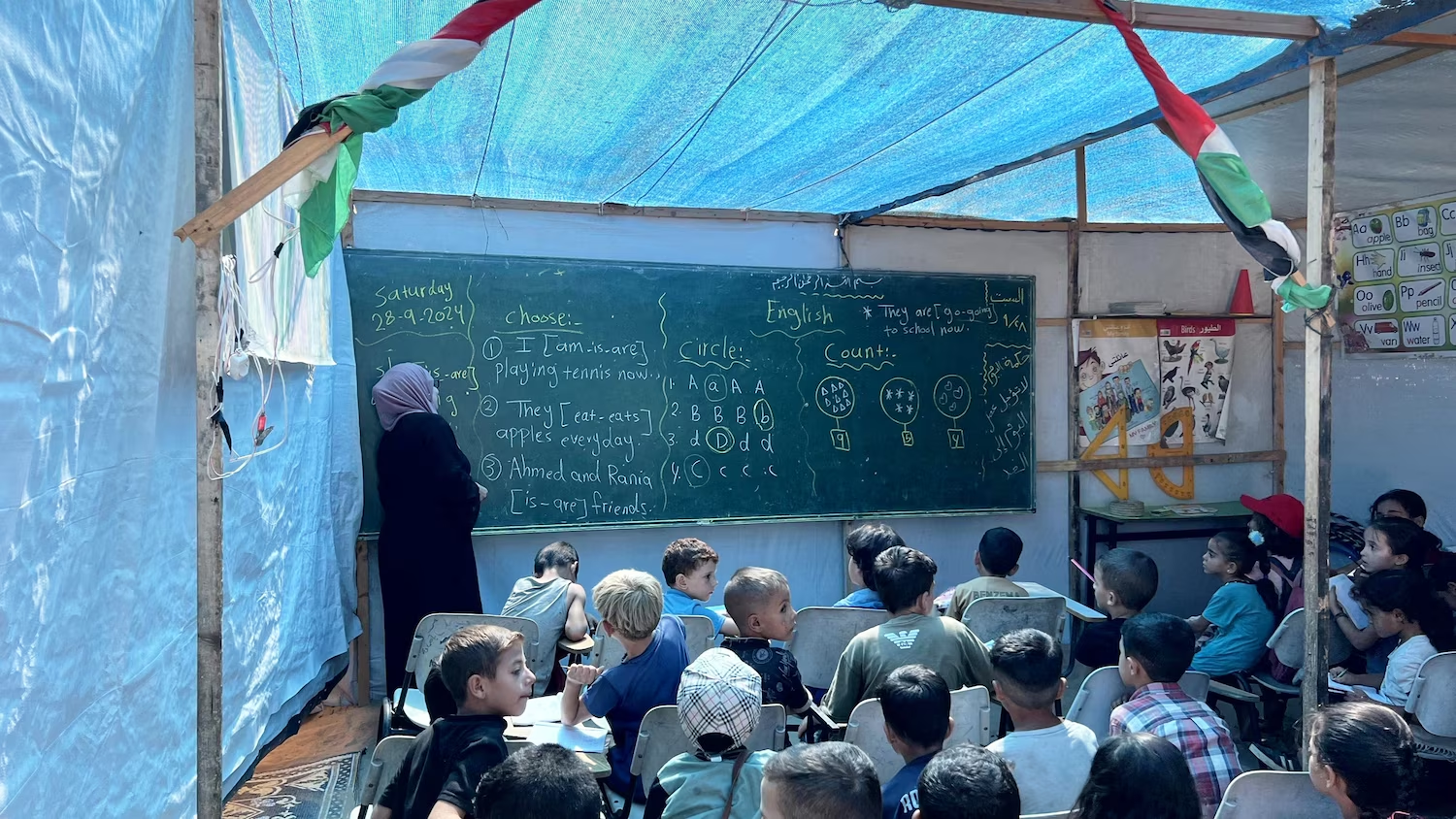

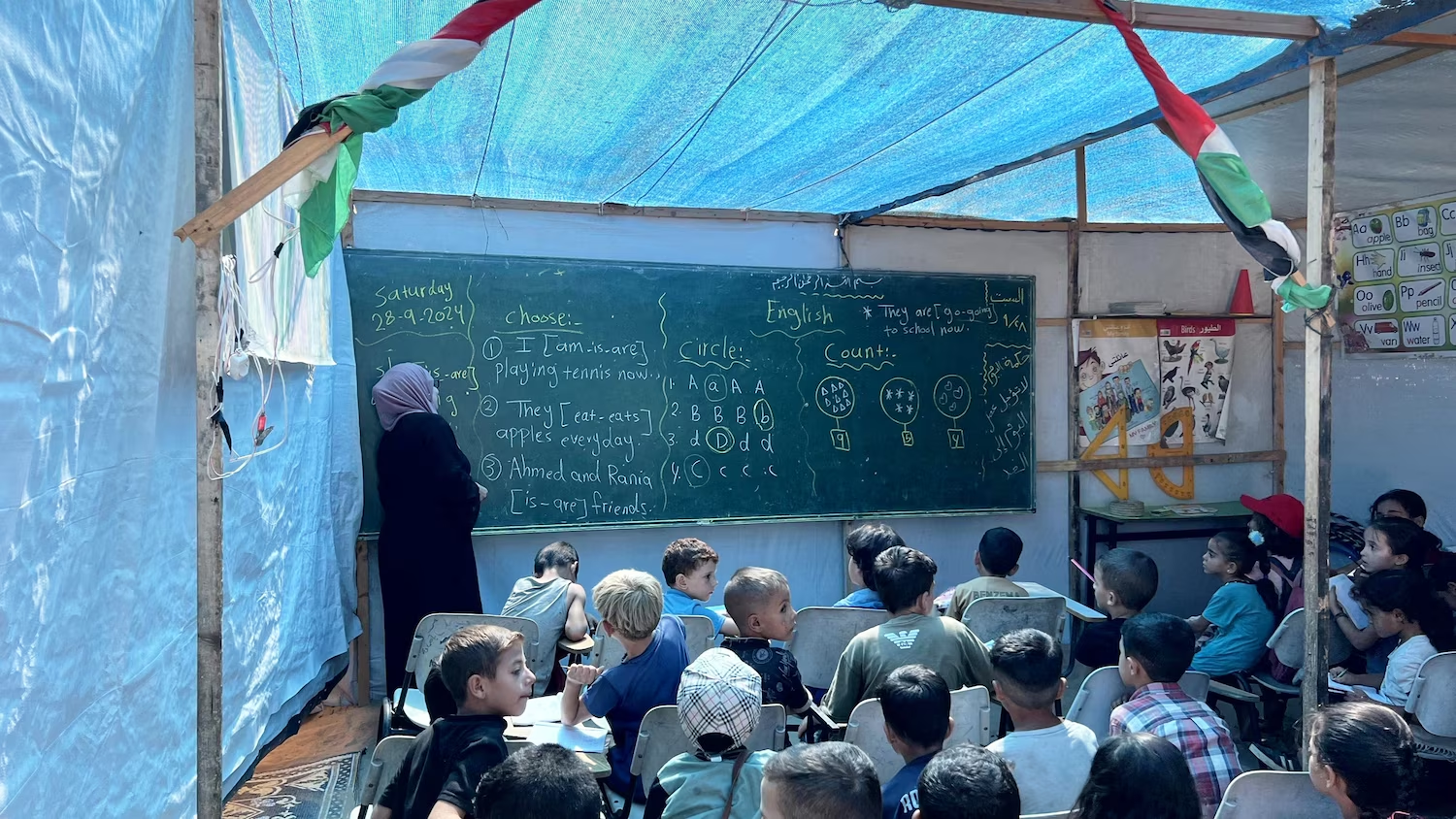

Teaching Against Erasure

Eleven-year-old Warda Radwan, who like many children and young folks in Gaza has lost two years of schooling, said simply that she was looking forward to returning to her learning routine. But what is she returning to, and how long can an education system last among ruins? Well, she is not waiting for an answer. Neither are the teachers holding classes in tents, the students organizing study circles in displacement camps, or the educators broadcasting lessons through whatever signal survives. “We built these universities from tents,” Gaza-based academics wrote in a letter last year. “And from tents, with the support of our friends, we will rebuild them once again.” This is what teaching and learning against erasure looks like, and it is happening now.

Teaching against erasure lives in the determined will of people to invent when everything familiar has been taken from them. It lives in Anwar, a university lecturer who goes tent to tent in displacement camps, gathering volunteer teachers, convincing families to offer their shelters on rotation so children have somewhere to learn. It looks like teachers showing up without salaries, printing worksheets at their own expense, because the alternative of doing nothing is unthinkable.

Resilience, in this landscape, becomes something almost elemental. It looks like Ikram Talaat Ahmed, the 29-year-old English teacher who lost everything when Israeli forces bombed Bureij camp—her home, her educational center and her job. Four of her colleagues were killed. Still, she turned her family’s displacement tent into a school for 200 children. “My resistance to the occupation is through education,” she says.

Community, under genocide, looks different. Displaced families vacating their shelter rooms three times a week so children can sit and learn. Teachers writing lessons on tent walls. One teacher described turning her tent into a space of healing—using drama, storytelling, weaving humanity into the wreckage. “These are acts of resistance,” she wrote. “But for how long?”

To learn under these conditions is an act of refusal. A refusal to be erased from both history and the future, a refusal to let the occupation define what is possible.

Colonialism Against Education

Colonizers have always understood that education is dangerous. And the colonized have always found ways to keep learning anyway.

When South Africa’s Bantu Education Act sought to limit Black children to menial labor, communities organized. Parents withdrew their children from government schools in the 1955 boycott, and activists formed “cultural clubs”—informal schools that operated illegally because unregistered education was banned. Buses collected children each morning and took them to learn in open fields, on the veld, taught by volunteers. The clubs were eventually crushed, but the resistance they seeded erupted again in 1976 when Soweto students rose against the system, and again in the 1980s when the People’s Education movement built hundreds of alternative educational organizations, smuggling banned copies of Paulo Freire’s pedagogy and training teachers for a post-apartheid future they insisted on creating.

Indigenous children in North America, forced into boarding schools designed to “kill the Indian and save the man,” resisted in quieter but no less stubborn ways. Students spoke their languages in secret, giving teachers derogatory nicknames in languages the authorities couldn’t understand, mocking the system while keeping alive the very thing it sought to eradicate. They ran away, repeatedly, even when forcibly returned. They used Plains Sign Talk, a shared sign language, to communicate across tribal lines when English was the only permitted tongue. What the schools meant to sever, students wove back together. The pan-Indian solidarity movements of the twentieth century trace their roots to the intertribal communities built in those very institutions meant to destroy them.

The educated Palestinian body has never been safe. To read, to teach, even the smallest act of passing a book from hand to hand has carried severe consequences under Israeli occupation. This has always been an act of defiance in the colonizer’s eyes. Israel has known this since 1948—libraries and archives looted during the Nakba, their pages scattered like the displaced, as if knowledge itself carried contagion.

Settler colonialism has always operated through elimination of not only the people, but also of the systems that allow a people to continue. Land and learning are taken together. This is why scholasticide cannot be dismissed as collateral damage. The Genocide Convention speaks of deliberately inflicting conditions calculated to destroy a group’s existence. Leveling every university, killing hundreds of educators, and burning archives and dissertations. Attacking them is a deliberate attack on the infrastructure of erasure.

Sumud Made Material

Sumud—steadfastness—has never wavered. In late November 2025, students walked back into the Islamic University of Gaza for the first time in two years. Medical students, nursing students filing into classrooms that only survived because they cleared the debris and said, we start here. Four thousand students graduated through remote learning during the war. Now the university is enrolling new students in person, coordinating a phased return with the Ministry of Education. “Today is a historic day,” the university president, Asaad Yousef Asaad, said. “We are returning to education despite the tragedy and cruelty left behind by the genocide.”

Just weeks later, in December 2025, another ceremony unfolded in front of the destroyed facade of al-Shifa Medical Complex. 168 Palestinian doctors, calling themselves the “Humanity Cohort,” graduated and received their Palestinian Board certifications amidst the rubble of what was once Gaza’s largest hospital. These healers were trained during and inside the genocide itself, becoming doctors by treating the very destruction that sought to ensure there would be no doctors left. Israel sought to destroy Palestine’s human capital throughout its attacks on healthcare facilities and means of medical education and training. Yet, the Humanity Cohort graduating even amongst ruins demonstrated what Palestinian Sumud looks like in practice: the active refusal to let genocide determine who gets to exist, learn, or heal.

The genocide after October 2023 was not the first attack on the pillars of what makes up Palestinian society, and Palestinians have resisted scholasticide before with schools built in refugee camps, to universities that held their first lectures in tents to literacy rates that defied the 18 years of blockade and siege. Palestinians have rebuilt their schools from nothing before, and will do so again with the stubborn insistence that a future exists because they are still there, because they themselves refuse to disappear.

Topics:

Filed under:

Location:

{

"article":

{

"title" : "Scholasticide in Gaza: On the Systematic Destruction of Palestinian Education",

"author" : "Jwan Zreiq",

"category" : "essays",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/scholasticide-in-gaza",

"date" : "2026-01-07 12:24:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/gaza-children-yahya-ht-jt-241003_1727999853116_hpEmbed_16x9.jpg",

"excerpt" : "",

"content" : "Gaza graduated its students in mid-November. In caps and gowns, students walked through the ruins, holding diplomas for an education they fought with their lives to keep alive. This is what resistance looks like when a society is being targeted for erasure.What Israel’s assault sought to destroy, the more than 97 percent of schools damaged or destroyed and all twelve universities reduced to rubble—Palestinians are rebuilding with their hands, their voices, and their refusal to simply disappear. Human rights experts raised the alarm back in April 2024, warning that Israel’s pattern of attacks on schools, universities, teachers, and students constitutes the intentional obliteration of the Palestinian education system. The term for this deliberate destruction of educational infrastructure is scholasticide: the systematic annihilation of education, the targeting of knowledge itself, of the capacity for a people to transmit their history and culture, and hence, their future. But Gaza, with one of the highest literacy rates in the world (97.7%), is answering erasure with something Israel cannot destroy with bombs: knowledge.The pursuit of knowledge has always been woven into the fabric of Palestinian identity, a form of resistance in itself, a way of asserting presence and possibility in the face of occupation and siege. Many Palestinians, including us in the diaspora, believe everything in life could be taken from us, all except for our education and knowledge.Teaching Against ErasureEleven-year-old Warda Radwan, who like many children and young folks in Gaza has lost two years of schooling, said simply that she was looking forward to returning to her learning routine. But what is she returning to, and how long can an education system last among ruins? Well, she is not waiting for an answer. Neither are the teachers holding classes in tents, the students organizing study circles in displacement camps, or the educators broadcasting lessons through whatever signal survives. “We built these universities from tents,” Gaza-based academics wrote in a letter last year. “And from tents, with the support of our friends, we will rebuild them once again.” This is what teaching and learning against erasure looks like, and it is happening now.Teaching against erasure lives in the determined will of people to invent when everything familiar has been taken from them. It lives in Anwar, a university lecturer who goes tent to tent in displacement camps, gathering volunteer teachers, convincing families to offer their shelters on rotation so children have somewhere to learn. It looks like teachers showing up without salaries, printing worksheets at their own expense, because the alternative of doing nothing is unthinkable.Resilience, in this landscape, becomes something almost elemental. It looks like Ikram Talaat Ahmed, the 29-year-old English teacher who lost everything when Israeli forces bombed Bureij camp—her home, her educational center and her job. Four of her colleagues were killed. Still, she turned her family’s displacement tent into a school for 200 children. “My resistance to the occupation is through education,” she says.Community, under genocide, looks different. Displaced families vacating their shelter rooms three times a week so children can sit and learn. Teachers writing lessons on tent walls. One teacher described turning her tent into a space of healing—using drama, storytelling, weaving humanity into the wreckage. “These are acts of resistance,” she wrote. “But for how long?”To learn under these conditions is an act of refusal. A refusal to be erased from both history and the future, a refusal to let the occupation define what is possible.Colonialism Against EducationColonizers have always understood that education is dangerous. And the colonized have always found ways to keep learning anyway.When South Africa’s Bantu Education Act sought to limit Black children to menial labor, communities organized. Parents withdrew their children from government schools in the 1955 boycott, and activists formed “cultural clubs”—informal schools that operated illegally because unregistered education was banned. Buses collected children each morning and took them to learn in open fields, on the veld, taught by volunteers. The clubs were eventually crushed, but the resistance they seeded erupted again in 1976 when Soweto students rose against the system, and again in the 1980s when the People’s Education movement built hundreds of alternative educational organizations, smuggling banned copies of Paulo Freire’s pedagogy and training teachers for a post-apartheid future they insisted on creating.Indigenous children in North America, forced into boarding schools designed to “kill the Indian and save the man,” resisted in quieter but no less stubborn ways. Students spoke their languages in secret, giving teachers derogatory nicknames in languages the authorities couldn’t understand, mocking the system while keeping alive the very thing it sought to eradicate. They ran away, repeatedly, even when forcibly returned. They used Plains Sign Talk, a shared sign language, to communicate across tribal lines when English was the only permitted tongue. What the schools meant to sever, students wove back together. The pan-Indian solidarity movements of the twentieth century trace their roots to the intertribal communities built in those very institutions meant to destroy them.The educated Palestinian body has never been safe. To read, to teach, even the smallest act of passing a book from hand to hand has carried severe consequences under Israeli occupation. This has always been an act of defiance in the colonizer’s eyes. Israel has known this since 1948—libraries and archives looted during the Nakba, their pages scattered like the displaced, as if knowledge itself carried contagion.Settler colonialism has always operated through elimination of not only the people, but also of the systems that allow a people to continue. Land and learning are taken together. This is why scholasticide cannot be dismissed as collateral damage. The Genocide Convention speaks of deliberately inflicting conditions calculated to destroy a group’s existence. Leveling every university, killing hundreds of educators, and burning archives and dissertations. Attacking them is a deliberate attack on the infrastructure of erasure.Sumud Made MaterialSumud—steadfastness—has never wavered. In late November 2025, students walked back into the Islamic University of Gaza for the first time in two years. Medical students, nursing students filing into classrooms that only survived because they cleared the debris and said, we start here. Four thousand students graduated through remote learning during the war. Now the university is enrolling new students in person, coordinating a phased return with the Ministry of Education. “Today is a historic day,” the university president, Asaad Yousef Asaad, said. “We are returning to education despite the tragedy and cruelty left behind by the genocide.”Just weeks later, in December 2025, another ceremony unfolded in front of the destroyed facade of al-Shifa Medical Complex. 168 Palestinian doctors, calling themselves the “Humanity Cohort,” graduated and received their Palestinian Board certifications amidst the rubble of what was once Gaza’s largest hospital. These healers were trained during and inside the genocide itself, becoming doctors by treating the very destruction that sought to ensure there would be no doctors left. Israel sought to destroy Palestine’s human capital throughout its attacks on healthcare facilities and means of medical education and training. Yet, the Humanity Cohort graduating even amongst ruins demonstrated what Palestinian Sumud looks like in practice: the active refusal to let genocide determine who gets to exist, learn, or heal.The genocide after October 2023 was not the first attack on the pillars of what makes up Palestinian society, and Palestinians have resisted scholasticide before with schools built in refugee camps, to universities that held their first lectures in tents to literacy rates that defied the 18 years of blockade and siege. Palestinians have rebuilt their schools from nothing before, and will do so again with the stubborn insistence that a future exists because they are still there, because they themselves refuse to disappear."

}

,

"relatedposts": [

{

"title" : "Nothing Is ”Apolitical”:: Why I Refused to Exhibit at the Venice Biennale",

"author" : "Céline Semaan",

"category" : "",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/nothing-is-apolitical",

"date" : "2026-02-24 15:51:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/Cover_EIP_Apolitical_Venice_Biennale-19ed6f.jpg",

"excerpt" : "After October 2023, the art world felt comfortable discriminating against Arab artists and dehumanizing us when Israel began carpet bombing Gaza leading to a genocide . For a few years since that moment, many Arab artists saw their work rejected, refused, or cancelled from shows, publications, and galleries. But in 2025, the propaganda against Arabs began to be debunked and the world recognized that Israel was in fact a colonial military occupation decimating Indigenous people, and curiously, we started receiving invitations to participate in the art world again.",

"content" : "After October 2023, the art world felt comfortable discriminating against Arab artists and dehumanizing us when Israel began carpet bombing Gaza leading to a genocide . For a few years since that moment, many Arab artists saw their work rejected, refused, or cancelled from shows, publications, and galleries. But in 2025, the propaganda against Arabs began to be debunked and the world recognized that Israel was in fact a colonial military occupation decimating Indigenous people, and curiously, we started receiving invitations to participate in the art world again.In the middle of last year, I was invited to exhibit my work at the Venice Biennale as part of their Personal Structures art exhibition. But unfortunately, I found myself needing to decline the invitation due to their separation between artistic practice and political reality: An expectation, stated and implied, that the work remain “apolitical.”For many artists, this is understood as an important recognition in one’s art career, a symbolic entrance into contemporary art history. Venice confers legitimacy, visibility, and, for many of us, validation from a historically extractive, colonial arts system. It also functions, like all major biennials, as an instrument of cultural diplomacy, soft power, and geopolitical storytelling. So a representation at the Venice Biennale as a Lebanese artist means a lot on a political scale.The word “apolitical” was used as part of a response that the Venice Biennale curator sent to justify their position regarding centering Israeli artists. It was an attempt to make explicit that engaging with the ongoing violence shaping the present moment, including the mass killing and destruction in Gaza, is a personal choice. That art exists without consequence, an elevated ideal that has the privilege of existing outside reality.I couldn’t tolerate pretending art was separated from politics, when Israel continues to bomb Lebanon daily, erase and sell Gaza, and murders Palestinians almost on a daily basis. Not when, just this February, Israel proposed to install a death penalty for the abducted Palestinians in Israeli jails with complete immunity. We are living through a time in which bombardment, starvation, displacement, and civilian death are documented in real time. Images circulate instantly; testimony is archived before bodies are buried. The evidence is not obscured by distance or ambiguity, but rather, is immediate, relentless, and impossible to ignore. Yet cultural institutions claim ignorance or worse, voluntary exclusion. In such a context, neutrality is not a passive stance but an alignment with injustice.Moral clarity is non-negotiable for me. It is my anchor in a time where global forces are unveiling their corruption for the world to see. In shock and despair, overwhelmed by the intensity of the crimes, many remain silent. Motionless. Like deers in the headlights. Hence, the safe label of remaining apolitical.But the myth of the apolitical artist has always depended on their proximity to power. It is a luxury position historically afforded to those whose bodies are not directly threatened by the carceral order. For many artists—particularly those shaped by colonization, occupation, exile, or racial violence—the political is not a thematic choice. It is the ground of existence itself.Arab women artists have shown me the path to moral clarity, integrity, and honor. The Palestinian American painter Samia Halaby has long argued that all art is political in its relation to society, whether acknowledged or not. For instance, Mona Hatoum’s sculptural language, often read through the lens of minimalism, is inseparable from histories of displacement and surveillance. The body remains present even when absent, reminding viewers that aesthetics do not transcend geopolitics.The Egyptian feminist writer Nawal El Saadawi warned with unmistakable clarity: “Neutrality in situations of injustice is siding with the oppressor.” Her words emerged from lived confrontation with imprisonment, censorship, and patriarchal state violence. Neutrality was never theoretical to her, it was lethal.Black feminist artists and thinkers have articulated the same truth. Audre Lorde’s assertion—“Your silence will not protect you”—dismantles the illusion that withholding speech preserves safety. Silence is participation in the maintenance of power. Lorraine O’Grady’s performances exposed how cultural institutions erase entire populations while claiming universality, revealing that visibility itself can be a political rupture. These perspectives converge on a single recognition: Art does not exist outside power structures. It either interrogates them or reinforces them.We remember artists who refused neutrality because their work altered the moral imagination of their time. Artists like Ai Weiwei, whose work centers politics and identity, go as far as putting their own bodies in danger. We remember the cultural boycott of apartheid South Africa, when artists refused lucrative opportunities rather than legitimize a racist regime. We remember Nina Simone transforming grief and rage into sonic resistance. We remember the Black Arts Movement insisting that aesthetics could not be detached from liberation.We also remember the artists who accommodated power. History is rarely generous toward them. The contemporary art world often performs political engagement while it structurally protects capital, donors, and institutional relationships behind closed doors. Calls for “complexity” or “nuance” frequently operate as ways to avoid taking positions that might threaten funding streams or geopolitical alliances. Requests for artists to remain apolitical are risk-management strategies that prioritize donors’ comfort.The insistence that artists claim they “do not know enough” to speak while mass civilian death unfolds is abdication. It mirrors political rhetoric that justifies violence through ideology, nationalism, or divine authority. Both rely on belief systems that absolve responsibility. The role of the artist is not to decorate power. It is to feel reality—to alchemize collective experiences into forms that expand perception rather than sterilize it.Art is essential precisely because we are living through rupture. But essential art is not decorative. It is not institutional ornamentation detached from consequence. It does not require erasing humanity in exchange for belonging to elite cultural circuits. Refusing the Biennale was not a heroic gesture. In fact, I had no desire to write this piece to begin with. It was just a form of moral clarity. Moral clarity some can live without, but unlike them, I refuse to become numb. I want to exist with a deep connection to my own humanity, and to feel it all.Including this moment that forces us to reckon with our own privileges and position. No exhibition, no platform, no symbolic prestige outweighs the responsibility of responding honestly to the conditions shaping our world. Participation under forced neutrality in accepting the presence of genocidal entities such as Israel would have required fragmentation — an agreement to pretend that art exists outside the systems producing suffering, including settler colonial violence and military occupation.It does not. And I cannot fake it."

}

,

{

"title" : "ICE Interference Is a Food Sovereignty Issue",

"author" : "Jill Damatac",

"category" : "essay",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/ice-interference-is-a-food-sovereignty-issue",

"date" : "2026-02-24 11:26:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/ice_food_soveriegnty.jpg",

"excerpt" : "Food inequality, like the carceral state, is not a bug, but a feature.",

"content" : "Food inequality, like the carceral state, is not a bug, but a feature.California National Guard troops face off with protestors during a federal immigration raid on Glass House Farms in Camarillo, Calif. on July 10, 2025. Photo Credit: Blake Fagan via AFPIn June 2025, ICE agents walked into Glenn Valley Foods, a meat plant in Omaha, Neb. and detained roughly half the workforce. Production sagged to a fraction of normal: Producers were already strained by drought, thinned herds, and high cattle prices. On paper and in headlines, the Trump administration claimed an enforcement success; on the plant floor, workers stayed home, choosing to lose wages rather than risk returning. Beef processors warned that if raids became routine, they would buy fewer animals, and bottlenecks would pinch slaughterhouses and feedlots. The systemic shock emerged in the price of ground beef, which edged, at one point, towards seven dollars a pound. Still, raids were sold to voters as proof of control, even as they paid more for food and meals.ICE actions against food workers, already exhausted and criminally underpaid, have a demonstrable effect on sky-high food prices and our tax dollars: Raids further strain an already fragile, extractive food production and service system by not only further funding violent carceral systems, but also our fiscal ability to put food on the table. And while it’s clear that much needs to be changed when it comes to how we treat food workers–from livable wages and health insurance to legal protections and affordable housing –one thing has not been properly acknowledged. ICE interference shapes how we eat and our ability to have food sovereignty.By definition, food sovereignty is, first and foremost, a claim to power. It is the right of communities, including immigrant food workers, to decide how food is grown, who profits from it, and what it costs. True self-determination means the land and our labor serve everyone, rather than corporations or government agencies. It means the price of food stays low and steady enough that working-class households eat well, that profits are shared so that small farmers, migrant workers, and food workers can live with dignity and comfort. But this is far from the reality we face today: with grocery and restaurant bills rising and food workers one threat away from deportation, what we are left with is a food system benefiting corporate interests, flanked by a carceral force wearing a false claim to justice as a mask.Immigrant food workers carry the nation’s appetite on their shoulders: According to a 2020 study by the American Immigrant Council, over 20% of food industry workers are immigrants. Within agriculture, 40-50% of workers are undocumented on any given year, while in the restaurant industry, undocumented immigrants are 10-15% of the workforce. Their work is in our carts, fridges, and pantries, on our restaurant tables, takeout counters, and drive-throughs. Workers are keenly aware that ICE knows exactly where to detainthem to hit their arrest quota: in fruit orchards and vegetable farms, meat processing plants, egg barns, dairy plants, grocery stores, restaurant kitchens, and even the parking lots where they gather at dawn, hoping to find work for the day. With agents detaining and deporting workers regardless of immigration status or criminal record, workers are scared into staying home, giving up precious income just to live another day. Meanwhile, fields go unpicked, stores scramble to cover shifts, and kitchens stall. Crews thin out rather than risk being taken, or, as in the case of Jaime Alanís García, are killed while fleeing an ICE farm raid.These calculations between fear and courage in the face of aggression are not abstract to me; they’re personal. My father was an undocumented immigrant who worked nights stocking a cereal aisle. He was given thirty-two hours a week, just shy of full-time, so the grocery store could avoid providing health insurance. When a new manager began to ask employees for identification, my dad and other undocumented co-workers quit, leaving the store scrambling to find people willing to work for minimum wage, nearly full-time, with no healthcare. These violent acts move through the food chain under the guise of “rising prices,” a surcharge in our grocery carts and restaurant bills.The U.S. government has played with the lives of immigrant food workers many times before. Under President Herbert Hoover during the Great Depression, “Mexican repatriation” campaigns deported hundreds of thousands of Mexicans and Mexican Americans, many of them farmworkers recruited in boom years, as officials caved to white workers, who were both unwilling to cede the work to immigrants or to take on the low-paying farm jobs themselves. Filipino farmworkers, known as the Manongs, were treated similarly: in the 1920s and 30s, Filipino workers slept in crowded bunkhouses, were paid low wages, worked through illnesses such as tuberculosis, and were given no path to citizenship, even though the Philippines was then a U.S. territory. In January 1930, white mobs in Watsonville, Calif. hunted Filipino men, beat them, threw them off bridges, and shot and lynched them. Soon after, California banned marriage between Filipinos and white people, and Congress slashed Filipino immigration to a token quota. The food industry has long built itself on brown people’s labor while the law denied them basic human rights. At the root of it all is a sinister plantation logic: a nation’s wealth and abundance built on enslaved Black people’s labor and deprivation. It’s just new bodies in the fields, now.Today’s arrests and deportations are a continuation of this very logic: exploited migrant workers are still denied basic rights and protections while the food industry that employs them grows, year on year. Many lack legal status; many more live in mixed-status families. Using the excuse of “border security,” ICE and DHS agents press on that vulnerability by design. As a result, fear of ICE enforcement becomes a cost itself, narrowing what people can afford and where they can eat. These enforcements, carried out without input the food industry or local communities, and often against their will, directly impact our food sovereignty—how people determine the way food is grown, distributed, made, and served, as well as how workers within the food industry are paid and treated.Take summer 2025 as an example: ICE raids swept through produce fields around Oxnard in California’s Ventura County, arriving in unmarked vehicles (and sometimes helicopters) at the height of harvest. The raids spread, so crews went into hiding: one Ventura County grower estimated that roughly 70% of workers vanished from the rows almost overnight, leaving farms heavy with rotting produce and no one to pick it. Economists modeling removals of migrant farmworkers from California estimate that growers could lose up to 40% of their workforce, wiping out billions of dollars in crop value and raising produce prices by as much as 10%.These losses are passed on to communities and households, obfuscating why and how the increases happened in the first place. The American consumer is consequently exploited, too, absorbing the real labor cost of detentions and deportations. In Los Angeles, immigration sweeps in June 2025 hit downtown produce markets and surrounding eateries; vendors called business “worse than COVID” as customers vanished and supplies wasted away in storage. In January 2026, along Lake Street in south Minneapolis, immigrant-run spots like Lito’s Burritos and stalls at Midtown Global Market, a popular food hall in downtown Minneapolis, saw revenue plunge due to ICE enforcement, forcing them to cut hours, or close altogether. In nearby St. Paul, Minn., El Burrito Mercado shut down after its owner watched agents circle the building “like a hunting ground.” Meanwhile, four ICE agents ate at El Tapatio, a restaurant in Willmar, Mn. Hours later, they returned after closing time to arrest the owners and a dishwasher. Hmong restaurants and Mexican groceries across the Twin Cities have gone dark for days or weeks at a time, suffocating the local economy, leaving consumers with shrinking access to food, and small business owners with no revenue while their employees go unpaid.If food sovereignty means real control over how food is grown, distributed, and accessed, it must begin with the safety of the workers holding the system up. Workers’ wellbeing is not ornamental: it is the precondition for steady harvests, stable prices, and an affordable Main Street. Federal and state legislation must build strict firewalls between labor and immigration enforcement so that workers can file complaints, call inspectors, or take a sick day without fear. Laws can enforce and extend safety protections, wage standards, and the right to unionize. This can only happen with comprehensive immigration reform: A durable legal status and a path to citizenship for food and farmworkers would help immigrant families break the old pattern of being extracted for labor while being denied the basic right to stability.There are also infrastructures that must be abolished to truly achieve food sovereignty: specifically, the burgeoning immigration detention industrial complex. The Big Beautiful Bill allocated $75 billion dollars, spread over four years, to ICE, funding the expansion of private prison facilities. Alongside the nation’s existing prison industrial complex, the immigration detention industrial complex has become a key economic driver, albeit one that benefits only a few, such as shareholders in CoreCivic and Geo Group, two of the nation’s biggest private prison companies.Food inequality and lack of food sovereignty, like the carceral state, are not bugs, but features: soaring food, housing, and healthcare costs, voter discontent, and public unrest form a feedback loop, reinforcing the manufactured narrative scapegoating immigrant and migrant workers. If enough Americans believe that immigrants are to blame for the high prices in grocery stores and restaurants, no one will pause long enough to scrutinize the corporations (and owners) who stand to profit.Should legislators have the courage to change the infrastructure that allows these inequities to occur, the hands that harvest, pack, cook, serve, and wash would be fairly recognized as part of the nation they feed. Because fear and imprisonment should never be priced into the dinner table. Everyone can—and should be able to—eat."

}

,

{

"title" : "To Grieve Together Is to Heal Together: Rituals of Care In Minneapolis",

"author" : "Joi Lee",

"category" : "essays",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/healing-rituals-minneapolis",

"date" : "2026-02-20 08:48:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/Lee_Minn_Image1.jpeg",

"excerpt" : "",

"content" : "Signs of resistance and community solidarity are found on every block, in every neighborhood. This is a sign a few houses down from Renee Good’s memorial. Photo Credit: Joi LeeOver the last three months, the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minn. have lived under siege. On December 4, 2025, the Department of Homeland Security announced the start of Operation Metro Surge as part of Trump’s crackdown on immigration. Around 3,000 immigration agents flooded into the region, turning Minneapolis into the epicenter for what would become the largest immigration enforcement operation in United States history.Neighbors watched other neighbors being abducted. The shrill sound of whistles—the warning sign that ICE was nearby—became the all-too-familiar soundtrack to the city. Streets, and the businesses that lined them, once bustling, became quiet, threatening the many diverse communities that form the cultural backbone of the Twin Cities: Somali, Hmong, Latine, among others.And then, on January 7, Renee Good, an everyday Minnesotan who was watching out for her neighbors, a legal observer, was shot and killed. Seventeen days later, Alex Pretti, an ICU Nurse, met the same fate at the hands of ICE officers.What followed made international headlines: civilians clashing with federal agents as flash bangs, tear gas, and rubber bullets filled the streets of Minneapolis. Images of confrontation traveled far beyond the city, flattening a much more complicated reality unfolding on the ground—as the news cycle has done repeatedly to Minneapolis over the years with the murders of Jamar Clarke in 2014, Philando Castile in 2016, and George Floyd in 2020 at the hands of police brutality.As tensions threatened to spiral further, the Trump administration announced a series of changes: replacing ICE commander Greg Bovino with so-called “border czar” Tom Homan, and on February 12, announcing that the operation in Minneapolis would come to an end. But in Minneapolis, many residents say the shift has been more cosmetic than substantive. Raids continue, surveillance lingers, and entire communities remain on edge.The fear has not lifted. It has settled.In this fragile uncertainty of what happens next, the Minneapolis community has turned to care. Across the city, people are gathering not just to strategize or protest, but to also grieve together: to light candles, pray, sing, and move their bodies in unison. Memorials for Good and Pretti have become meeting grounds. Healing circles, ceremonies, and music-filled vigils have emerged as lifelines for a community nowhere near recovered, yet refusing to unravel.Posters of Renee Good and Alex Pretti adorn the city, plastered on empty walls, hung up on store windows. Photo Credit: Joi LeeA legacy of trauma—and healingIn Minneapolis, trauma does not arrive without memory. Neither does healing.I met Leslie Redmond, an organizer and former president of Minneapolis NAACP, at a healing circle she convened the day after Pretti’s murder. Nestled in a small community cafe, tables were pushed aside and chairs brought into the circle. Wafts of warm home-made chili floated in from the vegan kitchen, and cups of piping hot lemon ginger tea—nourishing for the soul, we were assured—were handed out.As folks trickled into their seats, nervous chatter gave way to quiet realization that everyone was holding a pain that needed to be shared. Looking around the faces in the room, many etched with stress and exhaustion, Redmond reminded us, “Before we can build, we must heal.”Redmond is no stranger to collective trauma inflicted by the hands of law enforcement. She had lived through the police killings of Jamar Clarke, Philando Castile, and George Floyd, as well as the uprisings that followed.“Back then, I wasn’t actively healing. My back went out. My hair was falling out. We were in the fight phase. And then I realized, we need to move to the healing phase.”By the end of 2020, Redmond decided to create a community healing team for collective mourning. When Good was killed, that infrastructure, built slowly and deliberately, was ready to spring into action.“Healing is fundamental,” Redmond said, before quoting Audre Lorde’s seminal words from A Burst of Light: “Self-care is not self-indulgence. Self-care is self-preservation, which is an act of political warfare.”These days, Remond facilitates weekly healing circles. For many, the healing circles have become a place to reset. To find solace in knowing that what Minnesotans are going through is real, and not imagined. To find validation in their pain, yet also resolution in how to move forward. At one of the meetings, a 13-year-old quietly confessed to the group, “I feel like I’ve lost my peace.” At another, a Somali elder shared, “We’ve been living in fear. But looking around, how beautiful to remember why I decided to call this place my home.”Different cultures, shared medicine in memorialThe memorials of Pretti and Good, built at the sites where they were killed, have become living spaces of ceremony and connection. The rituals of healing are as diverse as the communities that Pretti and Good gave their lives to protect. At a vigil for Pretti organized by his fellow nurses, I met members of the Hmong community, an ethnic group that originates from Southeast Asia and largely came over as refugees to Minneapolis in the mid-1970’s. The Twin Cities are home to the largest concentration of Hmong people in the U.S.One person held a sign reading, “A Hmong shaman for healers & humanity!” Another read, “A Hmong Christian for healers & humanity!”A woman who asked me to call her Yaya explained why she was there. “As a healer from the Hmong community, as a shaman, I came to support them, healer to healer,” she said. “Because we do so much healing, but we forget to heal ourselves. Today is about healing the healers.”The group offered both prayers and blessed strings. People approached quietly, asking for care. Some requested Christian prayer, others a shamanic blessing. Kiki, the Christian, clasped their hands tightly, offering a prayer and a hug. Yaya took each person’s right hand, looping a thin string around the wrist and tying it gently in place, murmuring a prayer so soft it barely rose above the street noise.Many accepted both.Ceremony as resistanceIndigenous communities also organized ceremonies honoring Good and Pretti.Among them was a Jingle Dress Dance ceremony, rooted in Ojibwe healing traditions, meant to restore health and balance to those who need it. Over 30 members of the Minneapolis Native community came together at both memorials to perform their sacred dance, adorned in vibrant dresses. Metal cones are woven in intricate patterns around the dress, such that a slight movement creates a rhythmic sound.“The dress came to our people when there was a time of sickness. And so that’s what we do. We show up when there’s people suffering,” Downwind said, one of the organizers of the ceremony.Jingle Dress Dancers gather at Renee Good memorial’s site to perform a healing ceremony. Photo Credit: Joi LeeThe sound of metal cones sewn onto the dresses echoed through the cold air—each step a prayer, each movement an offering—was met with quiet attentiveness by the audience.When the dance finished at Good’s memorial, the crowd moved to Pretti’s, a journey that in itself felt like a pilgrimage, connecting the deaths of two Minnesotans with the lives of all those who remained, continuing their legacy.For many in attendance, the presence of Native dancers felt both sacred and a reminder that this land holds older traditions of survival. That healing did not begin, nor will it end, with this moment.**Music and the permission to feel **Music has also become a vessel for collective healing. Groups like Brass Solidarity,a band that was founded in response to the murder of George Floyd, have organized performances at the memorials, bringing instruments into spaces thick with grief.In the cold, unforgiving nights of Minneapolis, hundreds gather by Alex Pretti’s memorial site to listen to the musical tribute given by Brass Solidarity. Photo Credit: Joi LeeOne evening at Pretti’s memorial, hundreds of people stood shoulder to shoulder, bodies seeking warmth and rhythm. Brass instruments rang out, fingers braving subzero temperatures to play. Anthony Afful, a musician with Brass Solidarity, described the role of music in these spaces. “Part of what we’re doing,” he said, “is helping people remember that they’re human.”Music, he explained, creates room for the full range of emotion. “This is a dark time. There has to be space for grief, for rage, and also for joy—to exist together.”I spoke to another musician, Tufawon, who is Native-Boricua. For him, it is not just experiencing music but also its creative expression that helps unlock emotional processing. He’s currently holding a music workshop for Native youth, many of whom have been deeply impacted by ICE raids despite being the Indigenous peoples of this land.“As colonized people, we’re impacted by historical trauma,” Tufawon explained. “We carry it through our genes. And now there’s a collective trauma that the entire city, the entire state, really, is holding. We don’t take the time to process what we experience. Music is a mindfulness practice. So I use music to bring healing into the moment, so they can find some level of balance and not crash so hard when it’s all over.”Tufawon is a local Minneapolis artist, both Native and Puerto Rican, who uses music as an educational and community tool to heal and lift up the Native youth community. Photo Credit: Joi LeeHealing circles, ceremonies, music, and prayer: many of these are rituals with a rich, long history. They have navigated many cultures in the past and will continue to do so in the future.They have passed through countless cultures and generations, carrying meaning far beyond any single moment.But in a time where Minneapolis is being ripped apart—when the very definition of who belongs, of what it means to be an “American,” is under violent scrutiny—these rituals of care have reaffirmed something that cannot be detained, erased, or deported. That the very fabric of this place has been woven together by so many cultures, by so many peoples. And that it will be healed by them, together.Minneapolis is no stranger to rebuilding. It is a city, a sacred land, that is practiced in rising from devastation, again and again."

}

]

}