Digital & Print Membership

Yearly + Receive 8 free printed back issues

$420 Annually

Monthly + Receive 3 free printed back issues

$40 Monthly

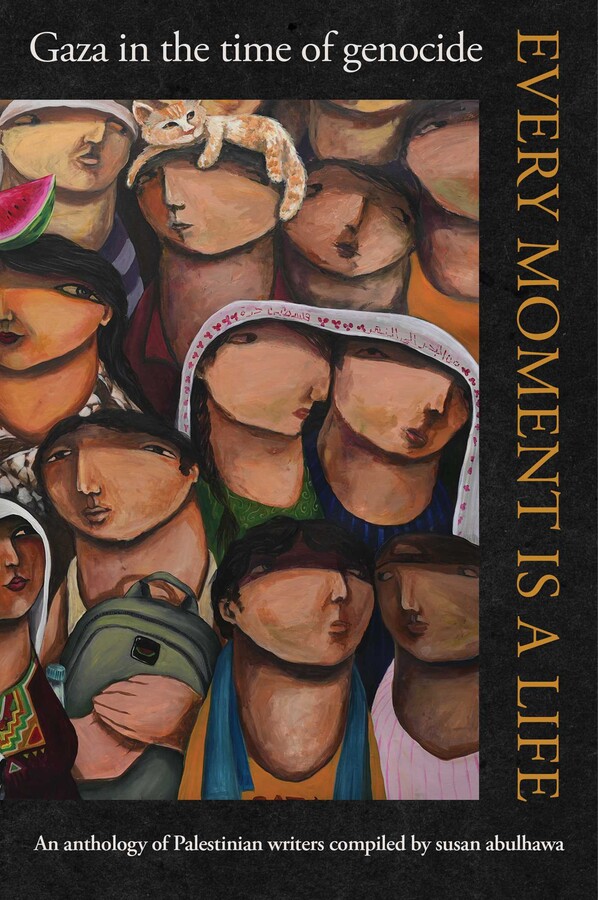

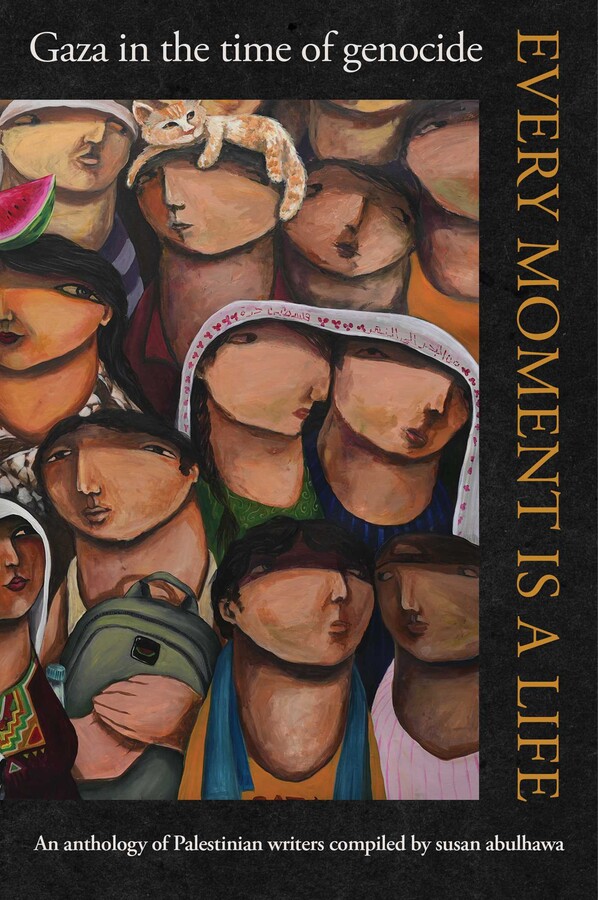

A Trail of Soap

From EVERY MOMENT IS A LIFE compiled by susan abulhawa. Copyright © 2026 by Palestine Writes. Reprinted by permission of One Signal Publishers/Atria Books, an Imprint of Simon Schuster, LLC.

Illustration by Rama Duwaji

I met Diana Islayih at a series of writing workshops I conducted in Gaza between February and May 2024. She was one of a couple dozen young people who traveled for hours on foot, by donkey cart, or in cars forced to crawl through the crush of displacement. They were all trying to survive an ongoing genocide. Still, they risked Israeli drones and bombs to be there, just to feel human for a few hours, like they belong in this world, to touch the lives they believed they might still have.

Soft-spoken and slight, Diana was the only one who recognized me, asking quietly if I was “the real susan abulhawa.” Each writer progressed their piece at their own pace, and would read their work aloud in the workshops to receive group feedback. Diana’s was the only story that emerged almost fully formed, as if it had been waiting for language. She teared up the first time she read it aloud, and again, the second.

By the third reading, the tears were gone. “I got used to the indignities,” she told me. “Now I’m used to reading them out loud.” She confessed that she struggled living “a life that doesn’t resemble me.” On our last day together, I reminded her of what she’d said. She smiled ironically. “Now I don’t know if I resemble life,” she said.

What follows is Diana’s story, written from inside that unrecognizable life, bearing witness not through spectacle, but through one intimate moment in the unbearable weight of the everyday. — susan abulhawa, editor of Every Moment Is a Life, of which this essay is part.

Courtesy of Simon & Schuster

I poured yellow liquid dish soap into my left palm, which instinctively cupped into a deep hollow, like a well yearning to be a well once more. I would need to wash my hands after using the toilet near our tent, though the faucet was usually empty. Water had been annihilated alongside people in this genocide, becoming a ghost that graciously deigns to appear to us when it wishes to—one we chase after rather than flee.

The miserable toilet was made of four wooden posts, wrapped in a makeshift curtain made from an old scrap of fabric—so sheer you could see silhouettes behind it. A blanket full of holes and splinters served as a “door.”

Inside, a concrete slab with a hole in the middle. You need time to convince yourself to enter such a place. The stench alone seizes your eyelids and turns your stomach the moment it creeps into your nose.

I thought about going to the damned, distant women’s public toilet. I hated it during the first weeks of our displacement, but it was the only one in the area where you could both relieve yourself and scrub off the dust of misery that clung to every air molecule.

It infuriated me that it was wretched and run-down, and the crowding only made it worse—full of sand, soiled toilet paper, and sanitary pads scattered in every corner.

“Should I go?” I asked myself, aloud.

I decided to go, taking one step forward and two steps back. I’d ask anyone returning from the toilet, “Is there water in the tap today?” and await the answer with the eagerness of a child hoping for candy.

“You have to hurry before it runs out!”

Or, more often, “There isn’t any.”

So we’d all—men, women, and children—arm ourselves with a plastic water bottle, which was a kind of public declaration: “We’re off to the toilet.” We’d also carry a bar of soap in a box, although most people didn’t bother using it since it didn’t lather and was like washing your hands with a rock.

I looked up and exhaled, staring into the vast gray nothingness that stared right back at me. Then I stepped out onto the sand across from our ramshackle displacement camp—Karama, “Camp Dignity”—though dignity itself cries out in this filthy, exhausted place, choked with chaos and a desperate scramble to moisten our veins with a drop of life.

The road was empty, as it was early morning, and even the clamor of camp life lay dormant at that hour. Still, I couldn’t relax my shoulders—to signal my senses that we were alone, that we were safe. My fingers remained clenched over the yellow dish soap, my hand hanging at my side to keep it from spilling.

I crossed the distance to the toilet—step by step, meter by meter, tent by tent. The souls who dwelled in them, just as they were, unchanged, their curious eyes fixed on me. I passed a garbage heap, shaped like a crescent moon, overflowing with all kinds of empty food cans—food that had ruined the linings of our intestines and united us in the agonies of digestion and bowel movements.

Something trickled from my palm—a thread of liquid that felt like blood dripping between my fingers, down my wrist in thickening droplets. My hand trembled, and my eyes blurred. I convinced myself—without looking—that it was all in my head, not in my hand, quickened my pace, my heartbeat thudding in my ears.

At last, I reached the only two public toilets in the area, one for men and the other for women, both encased in white plastic printed with the blue UNICEF logo.

Inside, I was met with the “toilet chronicles”—no less squalid than the toilet itself—unparalleled chatter among women who’d waited long hours in the line together.

The old women bemoaned the soft nature of our generation, insisting our condition was a “moral consequence” of our being spoiled.

Other women pleaded to be let into the toilet quickly because they were diabetic. They banged on the door with urgency and physical pain, like they would break in and grab the person behind it by the throat, shouting, “When will you come out?!”

The woman inside yelled back, “I’m squeezing my guts out! Should I vomit them up too? Have patience! Damn whoever called this a ‘rest room’!”

I looked around. A pale-faced woman smiled at me. I returned her smile, but my face quickly stiffened again, as if the muscles scolded me for stretching them into a smile. A voice inside me whispered meanly, What are you both even smiling about?

A furious cry rang from the other stall, “Oh my God! Someone is plucking her body hair! What are you doing, you bitch? It’s a toilet! A toilet!”

Another voice shot back, “Lower your voice, woman, and hurry up! The child’s crying!”

Two little girls stood nearby, with tousled hair, drool marking their cheeks, their eyes half shut. They were crying to use the toilet, clutching their crotches, shifting restlessly in the sandy corridor where we stood.

I was trying to push through to the water tap at the end of the hall, attempting to escape this tiresome, tragic theater. As my luck would have it, there was no water. I opened my palm. It too was empty. The yellow dish soap my mother bought yesterday was gone. All that remained was a sticky smear across my left hand and a long thread trailing behind me in the sand. Had it been dripping from my hand all along the way?

I twisted the faucet handle back and forth—a futile hope for even a thin thread of water. Not a single drop came.

My body sagged under the weight of rage, disappointment, fury, and a storm of unanswerable questions. I rushed through the crowded corridor of angry women, out into the street. I couldn’t hold back tears.

I wept, cursing myself and the occupation and Gaza and her sea— the sea I love with a weary, lonely love, just as I’ve always loved everything in this patch of earth.

I sobbed the entire way back. Without shame. I didn’t care who saw—not the passersby, not the homes or tents, not the ground I walked on. My grief rained tears on this land on my way there and back.

But the land’s thirst is never quenched—neither with our tears, nor with our blood.

My eyes were wrung dry from crying by the time I reached our tent. I collapsed on the ground, questions clamoring in my head.

Can a homeland also be exile?

Can another exile exist within exile?

What is home?

Is home the homeland itself, the soil of a nation?

Or is it the other way around—the homeland is only so if it’s truly home?

If the homeland is the home, why do I feel like a stranger in Rafah—a place just ten minutes from my city, Khan Younis?

And why did I fear the feeling I had when I imagined myself in our kitchen, where my mother cooked mulukhiya and maqluba for the first time in six months, even though I wasn’t at home—in our house?

That day, I said aloud, “Is this what the occupation wants? For me to feel ‘at home’ merely in the memory of home?”

How can I feel at home without being there?

How can I be outside of my homeland when I’m in it?

I looked down at my hand—dry and cracked with January’s chill. The yellow soap liquid had turned into frozen white powder between my fingers.

In Conversation:

Illustration by:

{

"article":

{

"title" : "A Trail of Soap",

"author" : "susan abulhawa, Diana Islayih",

"category" : "excerpts",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/a-trail-of-soap",

"date" : "2026-02-13 08:40:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/Trail_of_Soap.jpg",

"excerpt" : "From EVERY MOMENT IS A LIFE compiled by susan abulhawa. Copyright © 2026 by Palestine Writes. Reprinted by permission of One Signal Publishers/Atria Books, an Imprint of Simon Schuster, LLC.",

"content" : "From EVERY MOMENT IS A LIFE compiled by susan abulhawa. Copyright © 2026 by Palestine Writes. Reprinted by permission of One Signal Publishers/Atria Books, an Imprint of Simon Schuster, LLC.Illustration by Rama DuwajiI met Diana Islayih at a series of writing workshops I conducted in Gaza between February and May 2024. She was one of a couple dozen young people who traveled for hours on foot, by donkey cart, or in cars forced to crawl through the crush of displacement. They were all trying to survive an ongoing genocide. Still, they risked Israeli drones and bombs to be there, just to feel human for a few hours, like they belong in this world, to touch the lives they believed they might still have.Soft-spoken and slight, Diana was the only one who recognized me, asking quietly if I was “the real susan abulhawa.” Each writer progressed their piece at their own pace, and would read their work aloud in the workshops to receive group feedback. Diana’s was the only story that emerged almost fully formed, as if it had been waiting for language. She teared up the first time she read it aloud, and again, the second.By the third reading, the tears were gone. “I got used to the indignities,” she told me. “Now I’m used to reading them out loud.” She confessed that she struggled living “a life that doesn’t resemble me.” On our last day together, I reminded her of what she’d said. She smiled ironically. “Now I don’t know if I resemble life,” she said.What follows is Diana’s story, written from inside that unrecognizable life, bearing witness not through spectacle, but through one intimate moment in the unbearable weight of the everyday. — susan abulhawa, editor of Every Moment Is a Life, of which this essay is part.Courtesy of Simon & SchusterI poured yellow liquid dish soap into my left palm, which instinctively cupped into a deep hollow, like a well yearning to be a well once more. I would need to wash my hands after using the toilet near our tent, though the faucet was usually empty. Water had been annihilated alongside people in this genocide, becoming a ghost that graciously deigns to appear to us when it wishes to—one we chase after rather than flee.The miserable toilet was made of four wooden posts, wrapped in a makeshift curtain made from an old scrap of fabric—so sheer you could see silhouettes behind it. A blanket full of holes and splinters served as a “door.”Inside, a concrete slab with a hole in the middle. You need time to convince yourself to enter such a place. The stench alone seizes your eyelids and turns your stomach the moment it creeps into your nose.I thought about going to the damned, distant women’s public toilet. I hated it during the first weeks of our displacement, but it was the only one in the area where you could both relieve yourself and scrub off the dust of misery that clung to every air molecule.It infuriated me that it was wretched and run-down, and the crowding only made it worse—full of sand, soiled toilet paper, and sanitary pads scattered in every corner.“Should I go?” I asked myself, aloud.I decided to go, taking one step forward and two steps back. I’d ask anyone returning from the toilet, “Is there water in the tap today?” and await the answer with the eagerness of a child hoping for candy.“You have to hurry before it runs out!”Or, more often, “There isn’t any.”So we’d all—men, women, and children—arm ourselves with a plastic water bottle, which was a kind of public declaration: “We’re off to the toilet.” We’d also carry a bar of soap in a box, although most people didn’t bother using it since it didn’t lather and was like washing your hands with a rock.I looked up and exhaled, staring into the vast gray nothingness that stared right back at me. Then I stepped out onto the sand across from our ramshackle displacement camp—Karama, “Camp Dignity”—though dignity itself cries out in this filthy, exhausted place, choked with chaos and a desperate scramble to moisten our veins with a drop of life.The road was empty, as it was early morning, and even the clamor of camp life lay dormant at that hour. Still, I couldn’t relax my shoulders—to signal my senses that we were alone, that we were safe. My fingers remained clenched over the yellow dish soap, my hand hanging at my side to keep it from spilling.I crossed the distance to the toilet—step by step, meter by meter, tent by tent. The souls who dwelled in them, just as they were, unchanged, their curious eyes fixed on me. I passed a garbage heap, shaped like a crescent moon, overflowing with all kinds of empty food cans—food that had ruined the linings of our intestines and united us in the agonies of digestion and bowel movements.Something trickled from my palm—a thread of liquid that felt like blood dripping between my fingers, down my wrist in thickening droplets. My hand trembled, and my eyes blurred. I convinced myself—without looking—that it was all in my head, not in my hand, quickened my pace, my heartbeat thudding in my ears.At last, I reached the only two public toilets in the area, one for men and the other for women, both encased in white plastic printed with the blue UNICEF logo.Inside, I was met with the “toilet chronicles”—no less squalid than the toilet itself—unparalleled chatter among women who’d waited long hours in the line together.The old women bemoaned the soft nature of our generation, insisting our condition was a “moral consequence” of our being spoiled.Other women pleaded to be let into the toilet quickly because they were diabetic. They banged on the door with urgency and physical pain, like they would break in and grab the person behind it by the throat, shouting, “When will you come out?!”The woman inside yelled back, “I’m squeezing my guts out! Should I vomit them up too? Have patience! Damn whoever called this a ‘rest room’!”I looked around. A pale-faced woman smiled at me. I returned her smile, but my face quickly stiffened again, as if the muscles scolded me for stretching them into a smile. A voice inside me whispered meanly, What are you both even smiling about?A furious cry rang from the other stall, “Oh my God! Someone is plucking her body hair! What are you doing, you bitch? It’s a toilet! A toilet!”Another voice shot back, “Lower your voice, woman, and hurry up! The child’s crying!”Two little girls stood nearby, with tousled hair, drool marking their cheeks, their eyes half shut. They were crying to use the toilet, clutching their crotches, shifting restlessly in the sandy corridor where we stood.I was trying to push through to the water tap at the end of the hall, attempting to escape this tiresome, tragic theater. As my luck would have it, there was no water. I opened my palm. It too was empty. The yellow dish soap my mother bought yesterday was gone. All that remained was a sticky smear across my left hand and a long thread trailing behind me in the sand. Had it been dripping from my hand all along the way?I twisted the faucet handle back and forth—a futile hope for even a thin thread of water. Not a single drop came.My body sagged under the weight of rage, disappointment, fury, and a storm of unanswerable questions. I rushed through the crowded corridor of angry women, out into the street. I couldn’t hold back tears.I wept, cursing myself and the occupation and Gaza and her sea— the sea I love with a weary, lonely love, just as I’ve always loved everything in this patch of earth.I sobbed the entire way back. Without shame. I didn’t care who saw—not the passersby, not the homes or tents, not the ground I walked on. My grief rained tears on this land on my way there and back.But the land’s thirst is never quenched—neither with our tears, nor with our blood.My eyes were wrung dry from crying by the time I reached our tent. I collapsed on the ground, questions clamoring in my head.Can a homeland also be exile?Can another exile exist within exile?What is home?Is home the homeland itself, the soil of a nation?Or is it the other way around—the homeland is only so if it’s truly home?If the homeland is the home, why do I feel like a stranger in Rafah—a place just ten minutes from my city, Khan Younis?And why did I fear the feeling I had when I imagined myself in our kitchen, where my mother cooked mulukhiya and maqluba for the first time in six months, even though I wasn’t at home—in our house?That day, I said aloud, “Is this what the occupation wants? For me to feel ‘at home’ merely in the memory of home?”How can I feel at home without being there?How can I be outside of my homeland when I’m in it?I looked down at my hand—dry and cracked with January’s chill. The yellow soap liquid had turned into frozen white powder between my fingers."

}

,

"relatedposts": [

{

"title" : "Mark Zuckerberg Went to the Prada Show In Milan. It Wasn’t For Fashion",

"author" : "Louis Pisano",

"category" : "essay",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/mark-zuckerberg-prada-meta-glasses",

"date" : "2026-03-06 09:07:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/Pisano_Meta_glasses.jpeg",

"excerpt" : "When Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan took their seats in the front row at Prada’s Milan runway show on February 26, the photographs circulated quickly—the Meta CEO in his now-familiar uniform of expensive basics, watching models move down the runway in Miuccia Prada and Raf Simons’ latest vision of intellectual austerity.",

"content" : "When Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan took their seats in the front row at Prada’s Milan runway show on February 26, the photographs circulated quickly—the Meta CEO in his now-familiar uniform of expensive basics, watching models move down the runway in Miuccia Prada and Raf Simons’ latest vision of intellectual austerity.He was there because Meta is in active discussions with Prada to develop a line of branded AI smart glasses, a logical next step for a company whose Ray-Ban partnership has become one of the more surprising consumer electronics stories of the decade. Sales more than tripled in 2025, and on Meta’s January earnings call, Zuckerberg described them as “some of the fastest-growing consumer electronics in history.” The Oakley deal followed. Prada, if negotiations close, would be the latest luxury house recruited to solve a stubborn distribution problem: how to get people to wear a computer on their face without making them feel like they’re wearing a computer on their face. The answer, apparently, is to put it in a frame that costs as much as a car payment. The Meta Oakley Vanguards can be yours for the low cost of $549.Zuckerberg is not executing this pivot alone. Over the past year, tech’s richest men have staged a quiet, coordinated rebrand away from the founder-in-a-hoodie archetype toward something more deliberately cultured. Jeff Bezos has become a fixture in the fashion press, his aesthetic transformation carefully managed, his public image now signaling cultural seriousness alongside the financial kind. The underlying message from both men is consistent: that they are not the problem, but rather represent the future. And that the future can be beautiful and luxurious.This is what elite legitimacy looks like in our era of late-stage capitalism. When your industry faces sustained scrutiny across antitrust proceedings, data privacy legislation, and the slow erosion of public trust, you don’t just deploy lobbyists and communications teams. You acquire taste. You sit front row at shows with a century of cultural prestige behind them. You let the associations do work that no PR campaign could. Cultural capital operates differently from paid media; it feels earned, and its effects are harder to trace.Which is why the timing of Zuckerberg’s Milan appearance is worth examining more closely. At the same time that Zuckerberg was cementing a potential partnership with one of fashion’s most storied feminist houses, his company’s flagship wearable product was generating very different press coverage.In January 2026, BBC News investigated a pattern of male content creators using Ray-Ban Meta glasses to secretly film women during staged pickup encounters on the street, then uploading the footage to TikTok and Instagram as dating advice content. Dilara, a 21-year-old from London filmed on her lunch break, found her phone number visible in footage that had accumulated 1.3 million views, leading to a night of abusive calls and messages. Kim, a 56-year-old filmed on a beach in West Sussex, received thousands of inappropriate messages after her video reached 6.9 million views, and was still receiving them six months later. None of the women had seen any recording indicator. The BBC separately found YouTube tutorials demonstrating how to cover or disable the small LED light that Meta claims signals when the glasses are filming.The problem has spread internationally. In early 2026, a Russian vlogger traveled through Ghana and Kenya filming covert encounters with women using smart glasses (though it has not been confirmed that they were Meta-brand glasses) and posting footage to TikTok, YouTube, and a private Telegram channel where more explicit content was available by paid subscription. Some women were filmed in intimate situations without any knowledge that they were being recorded, let alone distributed to a global audience. Ghana’s Gender Minister confirmed that some victims were receiving psychological support, noting that exposure of this kind carries severe social consequences in conservative communities. Kenya’s Gender Minister called it a serious case of gender-based violence. Meta’s response, when asked for comment, was to point to the LED indicator light and its terms of service, a response that privacy advocates have consistently noted is equivalent to putting a “do not steal” sign on an unlocked car.Hundreds of similar accounts exist across TikTok alone, and the women who appear in them have had no recourse beyond reporting content that has already been viewed millions of times. These cases sit alongside The New York Times’ recent revelation of internal Meta plans for a feature called “Name Tag,” which would allow wearers to identify strangers in real-time by pulling data from Meta’s ecosystem of Instagram and Facebook profiles. Refuge and Women’s Aid told The Independent that this capability would pose a direct and serious risk to domestic abuse survivors, women who have rebuilt their lives at new addresses, hoping that distance and anonymity might be enough. Refuge reported a 62%rise in referrals to its technology-facilitated abuse specialist team in 2025, driven in part by wearable tech being used by abusers to monitor and control partners. Real-time facial recognition running on glasses indistinguishable from any other pair does not care about restraining orders.Into this landscape walks a potential Prada co-branded version of the same device. And there is something worth sitting with in the specific choice of Prada as Meta’s luxury target.Miuccia Prada has spent decades articulating, through her collections and in her public statements, a sustained engagement with feminist thought, grappling explicitly with how women are perceived, constrained, and resist the codes that govern their visibility in public and private life. The Prada woman, as a cultural figure, has never been decorative, according to Miuccia. She is thinking—and she is often acutely aware of being watched.Whether Miuccia Prada or the Prada Group’s leadership has genuinely reckoned with what women’s safety advocates have documented about the device they are being asked to co-brand is a question the company has not yet been asked loudly enough to their consumers. A Prada-branded pair of AI glasses would not simply be a licensing deal; it would be an aesthetic endorsement of the technology inside the frame, lending the cultural authority of a house that has built its identity around the intelligence and autonomy of women to Meta’s surveillance hardware.There is a term for what happens when corporations facing public scrutiny attach themselves to respected cultural institutions, when they fund museum wings, sponsor literary prizes, or plant themselves in the front rows of fashion weeks historically associated with progressive values. The association is meant to transfer accountability and even responsibility. The institution’s credibility flows toward the brand, and the brand’s controversies recede into the background noise of cultural life.Zuckerberg’s Milan appearance fits this pattern. A Prada partnership would give Meta’s smart glasses access to a female luxury consumer demographic they have struggled to reach, while simultaneously borrowing the feminist credibility of a house that has spent decades earning it, at the exact moment when critics, charities, and regulators are arguing most loudly that the product threatens women’s safety. The front row seat was not incidental to the pitch. It was the pitch.But the women who have had their faces filmed without consent, their phone numbers exposed to millions of strangers, their locations potentially traceable by the men who mean them harm, don’t get to sit front row or get a rebrand. What they get is a company whose products have been repeatedly documented and enabled their harassment, now aligning itself with a symbol of female empowerment, hoping the association does its work before the reckoning catches up.Miuccia Prada has built her career on the argument that what we put on our bodies makes an argument about the world. If she signs off on this, the argument she’ll be making won’t be the one she intended."

}

,

{

"title" : "Freezing Time with Matthew Johnson",

"author" : "Matthew Johnson",

"category" : "visual",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/matthew-johnson",

"date" : "2026-03-05 21:00:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/MJxSF_Iran_1.jpg",

"excerpt" : "What we are witnessing is beyond what words, analysis, or hot takes can capture. It is an impossible tragedy.",

"content" : "What we are witnessing is beyond what words, analysis, or hot takes can capture. It is an impossible tragedy.Through his photographic series “Screen Time”, Johnson uses long-exposure techniques to capture moving TV broadcasts, creating images to hold the intensity of these atrocious moments. Praying for the bombs to stop.Israeli intercepter missilesBeirutTehranDisplacement from the SouthRiyadh embassey attack (unconfirmed)Iranian drone strike on high rise in BahrainDubaiIranian missile launch"

}

,

{

"title" : "How to unpack and resist a pedophilic beauty standard: In a post-Epstein file world",

"author" : "Emma Cieslik",

"category" : "essays",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/how-to-unpack-and-resist-a-pedophilic-beauty-standard",

"date" : "2026-03-05 13:58:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/Justice_Store_13594585535.jpg",

"excerpt" : "In January, the Department of Justice released a 3,000,000-document drop of Epstein files which mentioned among others Les Wexner, the billionaire behind Victoria’s Secret and Abercrombie & Fitch among other brands. Although Wexner was already labelled a co-conspirator with Epstein by the FBI, this newest file drop raises questions about how Wexner–and by connection Epstein–were connected to clothing marketed towards young girls. In the aftermath, a whole generation of women are deconstructing how a pedophile was actively part of the marketing that eroticized and idealized prepubescent girls’ bodies as the ideal.",

"content" : "In January, the Department of Justice released a 3,000,000-document drop of Epstein files which mentioned among others Les Wexner, the billionaire behind Victoria’s Secret and Abercrombie & Fitch among other brands. Although Wexner was already labelled a co-conspirator with Epstein by the FBI, this newest file drop raises questions about how Wexner–and by connection Epstein–were connected to clothing marketed towards young girls. In the aftermath, a whole generation of women are deconstructing how a pedophile was actively part of the marketing that eroticized and idealized prepubescent girls’ bodies as the ideal.It is a reckoning with how American girlhood was shaped by men like Wexner and Epstein that informed not only the clothing that was marketed and sold to us but also the body shame that came with it, along with purity culture enforced by the very Christian leaders whose writings Epstein sent to his own victims.Birthday letter to Jeffrey Epstein attributed to Donald Trump. The text is censored due to potential copyright concerns (authorship of this work is disputed), though the rest of the piece is composed of simple shape and thus falls into the public domain.Wexner was the creator of L Brands, the retail company behind Victoria’s Secret, Bath & Body Works, and Abercrombie & Fitch, and owned TOO, Inc., the parent company of Justice and other brands marketed directly towards young girls. This past Friday, Wexner participated in a deposition to House Democrats about revelations from this latest file drop, claiming that he was “duped by a world-class con man.”Wexner notes that Epstein became his financial advisor back in the 1980s and at one point, served as his power of attorney. In this same deposition, Wexner revealed that he cut ties with Epstein after he discovered that Epstein stole over $100 million from him.Wexner called the accusations that he was part of Epstein’s sex trafficking “outrageous untrue statements and hurtful rumor, innuendo, and speculation,” claiming that his relationship with Epstein was strictly business. He also denied Epstein victim Virginia Giuffre’s claim that he was one of the men that Epstein trafficked her to. Wexner similarly denied knowing Maria Farmer, who accused Epstein of sexually assaulting her in 1996. Farmer claimed that after she was assaulted, Wexner’s security staff kept her on the property until a parent could pick her up, but Wexner said that “I never met her, didn’t know she was here, didn’t know she was abused.”But House Democrats repeatedly questioned how Wexner could not have known that this sex trafficking was happening and that it was fueled by his own money. The Democrats cast doubt on his story, arguing that “there would be no Epstein Island, no plane, no money to traffic women and girls without the support of Les Wexner.”While Victoria’s Secret sexualization of infantilized women is not new–we have known for years that the modelling industry behind Victoria’s Secret not only targeted children but sold people an ideal of beauty conflated with girlhood, this new file drop reveals that this was intentional by Wexner and others that sold us a form of girlhood that enabled predators.It’s no mistake that President Trump, another person mentioned over 38,000 times in the Epstein files, also owned Miss Teen USA pageants. In fact, in the deposition, Wexner said the only time that Jeffrey Epstein and Donald Trump would have interacted would have been at a Victoria’s Secret fashion show. Both attended fashion shows.But this latest Epstein file release is a wide scale realization that Wexner wasn’t the only one grooming a generation–think of what came out about producer Dan Schneider (who was also named in the Epstein files) after the release of the 2024 docuseries Quiet on Set: The Dark Side of Kids TV. Schneider oversaw the rampant, calculated sexualization of young actors.As children who watched Schneider shows and wore Wexner’s clothes, we are reckoning with the ways that many of us were exploited as children within a system marketing sexualized girlhood to us. Artist Sam Rueter put words to many people’s emotions following the latest Epstein file drop: “women in America are in deep grieving. Not because we are surprised or overcome with disbelief … but because we have to reckon with the cruel proof of our entire lives being a commodified, fetishized version of girlhood: and we are meeting, all at once, the children we were and could not protect.”In the aftermath, how can you reckon with and reject pedophilic beauty standards in the aftermath of the Epstein file drop?1. Do not spend money or support brands that sexualize children or infantilized models.While at first glance, this includes for many of us Victoria’s Secret, Abercrombie & Fitch, and other brands owned by Wexner, this also includes brands that market sexualized clothing or content to children. This month, the babycare brand Frida Baby came under fire for using phrases suggesting sexual innuendo on their baby products. The packaging had the phrases “I get turned on quickly,” “How about a quickie,” and “This is the closest your husband’s gonna get to a threesome.” Other brands like Balenciaga and Fashion Nova have also come under fire, but a number of other brands and fashion corporations are to blame–according to a 2011 study, ⅓ of all children’s clothing for girls is sexualized; “tween” stores like Abercrombie Kids, the study finds, are most to blame.In a capitalist society, sadly our most powerful tool is choosing where we spend our money, so it’s important to boycott and call out brands that sexualize children and market infantilized models.2. Do not consume and boycott any media sensualizing or sexualizing children by avoiding AI, social media platforms, and other content.Sadly in the age of AI, a number of digital platforms have been shown to generate and share sexualized images of minors, and according to the National Center on Sexual Exploitation (NCOSE), a number of online platforms including Instagram, Roblox, GitHub, eBay, Discord, X, Reddit, Spotify, and Snapchat fail to protect children from sexual content, putting them at risk for grooming and sexual exploitation. Avoid AI for this reason (among many others, including environmental impact) but also if you can, boycott social media platforms and call your representatives to urge the government to require these platforms to take actionable steps to protect children.This also applies to what may be some of your favorite Classic movies, television shows, or music, but know that by watching the movie, show, or consuming the content, you not only give your consent but also support its continued existence on streaming platforms. This is also a timely reflection given what has come out in the past three years about children on Nickelodeon; what once seemed innocent, at most odd, is revealed to be intimately connected to abusive behavior and sexualizing children.This also goes for new content, like the new season of America’s Next Top Model.3. Do not dress up as sexy babies, or sexualized children.While the Spirit Halloween costume section was full of sexy babies in the early 2000s, I hope it’s clear that any costumes that sexualizes children or infantilized adults contribute to the perception that sexualizing children is acceptable or funny. This is a simple step that you and others can take next Halloween when choosing your costume, or when engaging in kink and BDSM cultures.And if you are buying clothing for your children or those of friends and family, do not buy them clothing that sexualizes them. This includes snarky sayings like “lady’s man” on a baby’s smock or “heartbreaker” on a baby’s bib. While some people may brush it off, especially if the child can’t read, studies have shown.) that children may begin to view their bodies as sexual objects and may be treated differently, including being targeted by sexual predators.4. Do not police other people’s bodies, period.This may be harder for people who were raised in systems where unshaved armpits or unplucked eyebrows are seen as unkempt (spoiler alert, this is connected to transphobic, racist beauty standards), but pedophilic beauty standards are built not only on a beauty standard that idealizes not just a hairless body but also a small, underdeveloped one. Commenting on other’s bodies, even if it’s not meant to criticize their appearance, can contribute to body image issues, and at the root of pedophilic beauty standards are the very eating disorders glorified in the early 2000s.This beauty ideal (perpetuated not only by companies like Victoria’s Secret but by magazines, music corporations, and media companies that glorified baby-ified women) not only aided and abetted the development of eating disorders but also severe body dysphoria that persists to this day. I distinctly remember friends of mine that experienced amenorrhea, or the absence of regular periods, because of eating disorders. Without vital nutrients, their periods stopped coming regularly, and with it, the development of their bodies—stunting their growth. Many of them remain small or underdeveloped because of childhood eating disorders.The same marketing and cultural influencers that encouraged us that skinniness was not acceptable but necessary also enabled young girls to stop getting their periods, the one thing that many cultures identify as their transition to womanhood. To be clear, a child getting a period does not make them an adult.5. Start with your own beauty routine.Do you dislike shaving or waxing your legs, armpits or other parts of your body? Do you dread expensive, medically unnecessary skincare routines and Botox meant to glorify perpetually young bodies? Good news–you don’t have to do these things.While our American beauty standards are rooted in the model of a young girl, they are not absolute and they only change when people pressure corporations that have marketed these standards to us in order to sell their products. If you can (for cultural and sensory reasons, not everyone is able to), take the first step and reject the urge to shave, wax, pluck, or inject.As someone with autism, I admit that shaving my legs and armpits is a sensory issue informed by pedophilic beauty standards, but it’s still a practice that helps me feel at home in my body. None of these suggestions are asking you to reject what makes you feel at home in your body. Some of the body care processes that pedophilic culture has coopted are ones that help to affirm our genders–practices that affirm who we are and how we feel at home in our bodies should never be challenged, but these steps encourage us to think about what has informed not only our view of what is an attractive woman (often modelled after young girls) but also what a woman is.6. Reject transphobic, racist beauty standards. Consume brands that showcase models of diverse body and beauty types.Because the urge to wax, shave, and pluck our hair is not only rooted in pedophilia, it’s also rooted in White supremacist transphobia that essentializes the beautiful body as inherently thin, White and visually binary. Pedophilic culture is sexist culture is purity culture is racist culture is transphobic culture. Gender essentialism is the bedrock of sexist beauty standards that seek to make adult women feel bad about our bodies. Fighting transphobia goes hand in hand with fighting gender essentialist beauty standards and by extension, pedophilic ones too!In a capitalist economy, much of our power is defined by money. Use that to your advantage! Along with not supporting brands that sexualize children and infantilize adults, seek out brands that showcase and celebrate adult bodies. Some great ones include WRAY, SmartGlamour, Lucy & Yak, and Modcloth that purposefully create clothing for and highlight models of diverse body types.7. Encourage and embody body neutrality.In this same vein, embody body neutrality by refusing to assign value judgement to your body and others’ bodies. Body positivity is great, but it still assigns a value judgement to bodies–for many fat people like me, celebrating our bodies much less feeling beautiful in them is rare because of thinness culture (especially in the age of Ozempic), but assigning our bodies value judgements still exacerbates the problem. Bodies are bodies that help us to stay alive. Need helpful starting steps? Check out Jessi Kneeland’s 2022 book Body Neutrality: A Revolution to Overcoming Body Image Issues.8. Finally, reject new-age purity culture.Although the Purity Culture Movement of the late 1990s and early 2000s is already facing a public reckoning, other Christian groups are trying to rebrand purity culture for the next generation. Back in 2022, I wrote about how modern social media influencers like Girl Defined are rebranding purity culture for a new generation, and I have even argued that modern anti-trans legislation is a new form of purity culture policing queer bodies. Take note of where purity culture continues to exist and call it out!And importantly, fight school districts, religious institutions, and public spaces that enforce sexist clothing rules like the ones we all remember from childhood. The fact that young girls were told that we would distract not just our male classmates but also teachers is deeply upsetting and shifts blame onto children and victims rather than adults and predators.This is a deeply upsetting reckoning but one that we have to undertake personally and communally. I hope that these recommendations are helpful first steps to move towards unpacking the very beauty standards and sexualization that groomed a whole generation of girls and women."

}

]

}