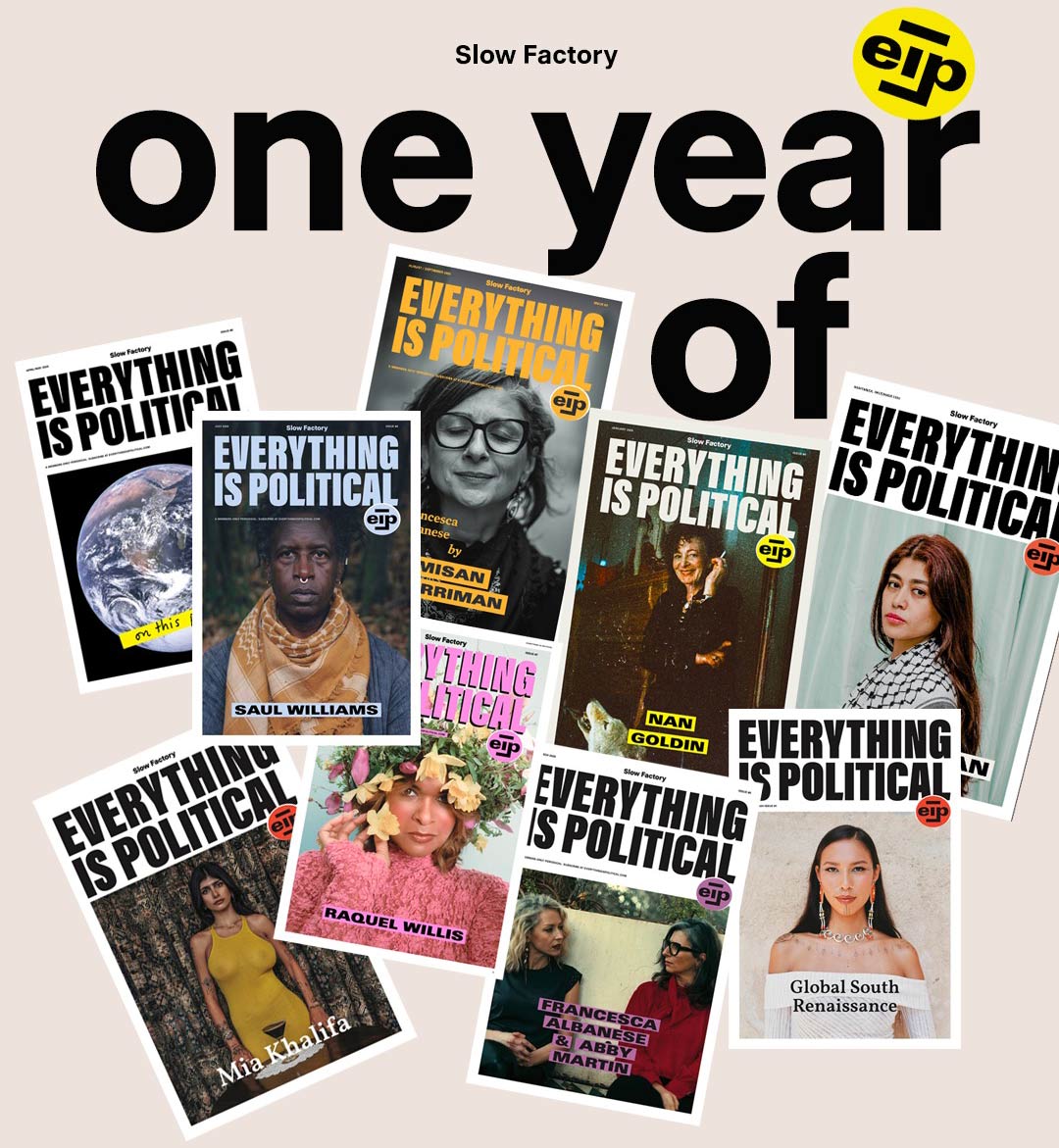

Digital & Print Membership

Yearly + Receive 8 free printed back issues

$420 Annually

Monthly + Receive 3 free printed back issues

$40 Monthly

The Waterbearers

Camille Billops

This excerpt from the Waterbearers by Sasha Bonét tells part of the story of artist and filmmaker Camille Billops. Told as a series of “tributaries”, the Waterbearers is a transformative work of American storytelling that reimagines not just how we think of Black women, but how we think of ourselves—as individuals, parents, communities, and a country. Published September 2025 by Penguin Random House.

Tributary #88

I

In 1961 at six o’clock on a spring morning in Los Angeles a group of Black women convene at the middle-class home of the family matriarch. There was probably tea and hushed whispers so as to not wake the child who rested in the next room. With all of their morning responsibilities abandoned and hair still tied back in rollers beneath silk scarves, they’ve gathered to convince one member of their tribe not to give her four-year-old child up for adoption. As they heard a car door shut in the driveway, one of the women peeped through the closed curtains to confirm the arrival of the member in question. Twenty-seven-year-old single mother Camille Billops entered, stoic and searching for her daughter, Christa Victoria. If, in fact, she housed any shame or doubt inside of her, there was no evidence of this on Camille’s being. The women—her mother, her mother’s sisters, and a few cousins—all made dibs on the child, as if she were up for auction. The strongest offers were that of Camille’s sister Billie and her mother, Alma, who had raised the child up until this point while Camille studied art and childhood education for physically handicapped children at Los Angeles State College at night and worked at the local bank during the day. Alma, too old and too tired, and Billie, married to a man whom Camille was suspicious of being unpredictable and unfit. “I’m going to take her. She’s mine,” Camille said, “and there’s nothing any of you can do about it.” Known for her smart mouth and uncompromising nature, Camille woke Christa up and walked her to the black Volkswagen Beetle and drove directly to the Children’s Home Society of California. She let go of Christa’s hand and told her to go to the bathroom; when Christa returned, searching for her mother, she looked out of the window, grasping her small teddy bear, and watched the black Bug drive away.

Camille had met Christa’s father, Stanford, through a mutual friend and their brief yet intense courtship ended abruptly. Stanford, a tall striking lieutenant in the US Air Force was stationed in California. A few months into their relationship Camille was pregnant, despite her realization at the age of ten that she didn’t want to be a mother, but abortions weren’t legal in California until 1969. If they were going to do this, they had to do it traditionally, and Stanford consented. Five hundred shotgun-wedding invitations went out and before the guests received them by mail, he was gone. Camille called around searching for him and the Air Force informed her of his military discharge. When Christa was born on December 12, 1956, Camille received a postcard, “Wishing you well, Love Stanford,” with no return address. He continued these cruel communications for years until he mistakenly wrote his return address; he was living in New York City on Pitt Street. With three-year-old Christa on her hip, Camille booked a flight across the country and sat on the stoop waiting for him to arrive home. Stanford pulled up in a Cadillac convertible, wearing sunglasses and a slight smile. He greeted them like old friends. Invited them in for beverages and shortly after showed them to the door, wishing them both all the best. Camille never saw him again. Christa reunited with this stranger three decades later and asked him if he was her father, and he replied, “I suppose so,” to which she said, “I’m glad we got that squared away.”

II

Was it in this moment that Camille decided to abandon motherhood? Or was it many moments that led to her dropping Christa off and speeding away? Christa, along with Camille’s family, believe it was an affair she was having with a White man named James Hatch. Her stepsister Josie was his student at UCLA in the theater department in 1959, and she introduced Camille and Jim. Knowing that Camille was single, she said, “He’s ready.” Camille was teaching then in the public school system and making ceramics at home. She asked Hatch to come over and take a look at her pots and he asked her to audition for a play he cowrote with UCLA colleague C. Bernard Jackson inspired by the Greensboro, North Carolina, student sit-ins, Fly Blackbird. She was never quite as good at acting as she had hoped and was selected for the chorus, but she was onstage at the Metropolitan Theater in LA. Jim was the first person to tell Camille she was a good artist. “I will always love him for that,” she says. His support provided her with permission to be whoever she pleased in any given moment, even if that meant not being pretty, what her family said a woman must be at all costs. This introduced Camille to a new way of being. A world of artists and activists, organized by the American Civil Liberties Union, who began protesting school segregation and Black oppression. At the height of the Civil Rights Movement, Camille was the mistress of a White man who believed in her, and despite Los Angeles being on the precipice of the Watts Uprising, she was not deterred by the vile language and glares thrown at them by strangers. Camille began slowly shedding the cultural influences of middle-class Black America. Her parents had come to California during the Great Migration, like many Southern Blacks who moved west in search of opportunity and the possibility of providing their family with security from the violence inflicted on Black bodies. In LA they worked in service to White folks, therefore it wasn’t necessarily work that they couldn’t attain in the South, it was their dignity. Her father, Luscious, from Texas, was a cook and her mother, Alma, from South Carolina, was a domestic and seamstress. However, escaping the South in physicality doesn’t remove the emotional traumas of being Black in America; their White ideals were held firmly intact and their Southern traditions folded neatly within. Whiteness was still seen as superior in eloquence and refinement and the Billopses would emulate this in their home, for appearances’ sake, but when the burlap curtains closed at night, Luscious drank like a fish until he passed out and his wife carried him to bed each night. Alma bestowed these beliefs of Black female servitude on her two daughters, and they consented, but the youngest child will always rebel, and for Camille, Jim was the catalyst. She had been taught that motherhood and womanhood were inextricable. If you were not a mother, then what would you be? Mother is to be a woman’s highest title, and anything that takes precedence, even your own dream, is deemed selfish. Images of Camille with baby Christa show a polished and respectable young lady with permed hair and slicked-down edges. But in the images with Jim, you can see the physical transformation. She cuts off her permed roller set curls and has a small perfectly picked Afro. The hairs along her top lip thicken and grow wildly, untamed. Camille preferred to be called artist, not mama. She had never allowed Christa to call her Mama, she was to call her Bootsie, like all of her closest friends and family. Jim also suspected that Camille was giving up Christa for him and offered just enough discouragement to absolve himself of responsibility, “Don’t give Christa up for me.” When Jim was offered a Fulbright appointment to teach at the High Institute of Cinema in Cairo, Egypt, the center of the 1960s Pan-African movement that brought over many young American artists and activists like Maya Angelou and Malcolm X, he asked Camille to come visit before his wife and kids arrived, and without hesitation she went. But before departing Cairo, she told him she would not return unless he left his wife and children. “He met me at the airport and his wife left,” she says, “we chose each other and entered into another life. That’s when the world opened.”

In Cairo, Camille began experimenting with sculpture and her first solo exhibition at Gallerie Akhenaton was a small collection of ceramic pots and sculptures of those close to her, like Jim, who would serve as her constant muse, benefactor, and advocate. Their intimacy and artistry were to always exist intertwined given the racially charged political unrest that they protested in their life and through their creations. They dared to love each other in a time when interracial relationships were still considered criminal in the United States. Their first collaboration was a book of poetry called Poems for Niggers and Crackers, published in Cairo in 1965, with poems written by Jim and American poet Ibrahim Ibn Ismail; Camille created the illustrations. Driven by all that she had sacrificed, Camille explored any medium she could get her hands on, photography, painting, printmaking, and eventually film, which would be her most critically acclaimed work. She spent many years creating and showing work in Egypt, Germany, and China before returning to her homeland after John F. Kennedy’s assassination, to find her own countrymen not so welcoming to Black women artists. They settled into New York City’s East Village where the Armenian American English professor and author Leo Hamalian helped Jim secure a teaching position in theater at City College while Camille taught ceramics there. As with all great artists, there comes a time when you must turn inward and begin dissecting yourself, to become the subject of your own examination. This led Camille into filmmaking.

III

Camille tells me:

“I was with all of the various Nigga bitches. Emma Amos, Faith Ringgold, Elizabeth Catlett. They had Black night at museums like the Whitney where they would let us in the building but not show our work. We were fighting so hard to get into the Brooklyn Museum and they wouldn’t let us in. So we said, well fuck you and the horse you rode in on. I said, you know what, I’m making my own way. So we bought this big-ass loft a long time ago when it was cheap. I told Jim, why don’t we buy a loft, and we did it. Jim had most of the money. I had a little something to contribute. I told him I wanted my name on it, and he said okay, so we got married. We are all we have. I would have never ended up being a working artist if it weren’t for him. His favorite words were ‘Why not?’ and ‘Yes you can.’ We created a library space, a studio in the back, an archive, and the dining area is where we host salons for our publication Artist and Influence. Every Black artist of our time has sat right here in this living room, and we recorded it all—bell hooks, Julie Dash, Amiri Baraka, all the Niggas. We invited everybody here: friends, students, and White gallerists and curators. We sold art right off our walls. I stopped begging a long time ago when I discovered I could sell art without having to kiss booty. These alternatives made it possible. Bob Blackburn was very helpful, he taught me printmaking. There were many artists that I met at the print shop while I was working, like Romi [Romare Bearden]. This is what you do when people don’t let you into their playground. We did it out of defiance. I always did whatever I wanted to do.

“In the early ’80s Christa found me. It was a great shock to me. She sent a letter and a cassette tape with a song, asking me if I would see her. She was twenty-something. I was scared because I had already learned how to live with my guilt about giving her up. I wasn’t trying to come out from beneath the water. I was never a very good mother. I did what was best for both of us. I was twenty-three and I hardly saw her when she was little, she was always with my sister Billie or my mama. Mothers are supposed to protect, and the only way I could do that was by giving her up. I didn’t see this as feminist then, I just knew I wanted to reverse it, I wanted to be free of motherhood. I agreed to meet with her. Jim really liked her, and they got on. Naturally, she was an artist like me, it’s in her blood. When I started making films, she helped us. You can hear her voice singing on the opening scene of Suzanne, Suzanne about my niece’s drug addiction and her abusive father. People wasn’t talking about domestic violence back then. Our films had a tendency toward dirty laundry, they say it like it is, not like it’s supposed to be. It was hard enough being Black so everyone wanted to appear perfect, keep up appearances, you know. My sister wanted to take Christa but I didn’t trust my brother-in-law, Suzanne’s father. Her adopted mother, Margaret, was fabulous, a jazz singer. She was the little ship that helped me sail the dangerous night. Then we made the film Finding Christa. Christa stayed here with us for a while when we were making the film and then she moved to New York to study, so I could help her become a singer. We were always fighting because she wanted me to feel guilty. She kept asking me why I gave her away. It was always verbally violent, and guilt-ridden. I was all kinds of bitches to her. She wasn’t easy. I tried to explain to her that I didn’t want to be a mother. But it was complicated. Jim says we were too much alike. She’s a Sagittarius and I’m a Leo, too much fire. She was a star in Finding Christa. People say I show no remorse in the film, they say I’m cold, but if I had to do it again I would. I know I made the right decision, wouldn’t change a thing. Well, the only thing I would do differently would be to give her up earlier. But it was hard. Her father disappearing on me was a gift, otherwise if he had stayed, I would have just endured, that’s what Black women did in my family, endured. Christa was a very good actress, and this was a part of our competitiveness. She took up space in a way that was threatening to me. This caused a big friction when she was staying with us. Adoptees have what they call ‘the great wound,’ and it would always come back to, ‘Why did you throw me away?’ She would come and stay here and see everything that we have built and turn to me and ask, ‘Why wasn’t I here? Why wasn’t I a part of this?’ Jim welcomed her with open arms. But I didn’t like her taking up so much space here. I would correct her and let her know, ‘This ain’t your place. You don’t own this.’ She was even beginning to claim the film, saying it was her film. I said, ‘Now wait a minute, you didn’t shoot that film. I shot that film. I cut that film.’ She wanted to be a filmmaker but want and spit are two different things. Yeah, so I suppose there was some essence of competitiveness. She was difficult, I was difficult. We had an argument and then she walked out one day. Then one day she returned. It didn’t last. It became argumentative again. Then she left again in 2013. We didn’t talk again. I let it go. She had become ill and had to have an operation. Then she needed another one and she said she wouldn’t have it. She killed herself by not taking that operation. I wasn’t invited to the funeral. When she died somebody called to tell me. Who was it that called me? I don’t remember. It was early in the morning. Like a blast from the furnace. You have to stand very still and face it. Then I had to bury it. Jim and I both. And that was it. It has to have a place. I’ve accepted the guilt. I will carry it with me forever. Sometimes I feel her when I am working.”

IV

Before Christa’s death she shared a letter on her Facebook page in 2014 titled “Given up Twice—Is It All Worth It?” In the letter she speaks about calling her stepfather, Jim, on Father’s Day 2013 and Camille also picking up a receiver in a different room and abruptly hanging up when Christa announced herself. Half an hour after the call Christa receives an email from Jim stating that she should never call or visit their home again. Christa suspects that this email was written by Camille, as it contains a “callous” brashness that isn’t indicative of Jim’s character toward her. The email stated that both Jim and Camille were “cutting all communications” with her, including “telephone, letters, on the internet and personal appearances on the tai chi court,” as she was causing too many disruptions in their lives. The email was signed by Jim and sent from his account, but the statement “four-year-old child continues to protest her mother’s decision for giving her up” were words that she had heard endlessly from her biological mother. Christa never spoke to Camille again, but after seeing a therapist, she concluded that Camille was uncomfortable with Christa’s intimate relationship with Jim. Thirty-two years after reuniting, Christa was dismissed. This three-thousand-word letter is filled with discreet anger, confusion, hurt that reads like a muffled scream into the abyss of social media. She signed the letter, “Christa Victoria (my name since birth).”

In the film Finding Christa, which won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance, making Camille the first Black woman producer/director to be awarded this prize, Christa says that she felt like an octopus, wanting to extend all parts of herself around the woman who birthed her, but Camille felt like a cactus, sharp and defensive. Christa also states that meeting her birth mother and biological family saved her life, but one may consider their final split to be the event that led to her demise. Camille challenged assumptions about what a Black middle-class woman had to be and chose her artistry above all else; despite her family’s beliefs that she chose Jim, she was choosing herself. To assume that Camille prioritized her relationship with her life partner seems misplaced and in contradiction to her radical act, which was to choose herself even when everything around her said that her purpose was to serve, soothe, and comfort, a rejection to the concept of Mammy.

Camille’s genius lay in her ability to imagine Black futures in a country that did not value Black life and the expression of that life through art. Before Roe v. Wade, before the Loving v. Virginia ruling, she made decisions that seemed improbable.

The future that Camille envisioned was one that benefited the well-being and advancement of not just one individual being that she birthed but an entire generation of artists and scholars who were nourished by her contributions as an artist and archivist. Christa, unfortunately, was a casualty in Camille’s ambitious defiance.

{

"article":

{

"title" : "The Waterbearers: Camille Billops",

"author" : "Sasha Bonét",

"category" : "excerpts",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/the-waterbearers-camille-billops",

"date" : "2025-09-08 10:04:00 -0400",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/Camille-and-Christa.jpg",

"excerpt" : "This excerpt from the Waterbearers by Sasha Bonét tells part of the story of artist and filmmaker Camille Billops. Told as a series of “tributaries”, the Waterbearers is a transformative work of American storytelling that reimagines not just how we think of Black women, but how we think of ourselves—as individuals, parents, communities, and a country. Published September 2025 by Penguin Random House.",

"content" : "This excerpt from the Waterbearers by Sasha Bonét tells part of the story of artist and filmmaker Camille Billops. Told as a series of “tributaries”, the Waterbearers is a transformative work of American storytelling that reimagines not just how we think of Black women, but how we think of ourselves—as individuals, parents, communities, and a country. Published September 2025 by Penguin Random House.Tributary #88IIn 1961 at six o’clock on a spring morning in Los Angeles a group of Black women convene at the middle-class home of the family matriarch. There was probably tea and hushed whispers so as to not wake the child who rested in the next room. With all of their morning responsibilities abandoned and hair still tied back in rollers beneath silk scarves, they’ve gathered to convince one member of their tribe not to give her four-year-old child up for adoption. As they heard a car door shut in the driveway, one of the women peeped through the closed curtains to confirm the arrival of the member in question. Twenty-seven-year-old single mother Camille Billops entered, stoic and searching for her daughter, Christa Victoria. If, in fact, she housed any shame or doubt inside of her, there was no evidence of this on Camille’s being. The women—her mother, her mother’s sisters, and a few cousins—all made dibs on the child, as if she were up for auction. The strongest offers were that of Camille’s sister Billie and her mother, Alma, who had raised the child up until this point while Camille studied art and childhood education for physically handicapped children at Los Angeles State College at night and worked at the local bank during the day. Alma, too old and too tired, and Billie, married to a man whom Camille was suspicious of being unpredictable and unfit. “I’m going to take her. She’s mine,” Camille said, “and there’s nothing any of you can do about it.” Known for her smart mouth and uncompromising nature, Camille woke Christa up and walked her to the black Volkswagen Beetle and drove directly to the Children’s Home Society of California. She let go of Christa’s hand and told her to go to the bathroom; when Christa returned, searching for her mother, she looked out of the window, grasping her small teddy bear, and watched the black Bug drive away.Camille had met Christa’s father, Stanford, through a mutual friend and their brief yet intense courtship ended abruptly. Stanford, a tall striking lieutenant in the US Air Force was stationed in California. A few months into their relationship Camille was pregnant, despite her realization at the age of ten that she didn’t want to be a mother, but abortions weren’t legal in California until 1969. If they were going to do this, they had to do it traditionally, and Stanford consented. Five hundred shotgun-wedding invitations went out and before the guests received them by mail, he was gone. Camille called around searching for him and the Air Force informed her of his military discharge. When Christa was born on December 12, 1956, Camille received a postcard, “Wishing you well, Love Stanford,” with no return address. He continued these cruel communications for years until he mistakenly wrote his return address; he was living in New York City on Pitt Street. With three-year-old Christa on her hip, Camille booked a flight across the country and sat on the stoop waiting for him to arrive home. Stanford pulled up in a Cadillac convertible, wearing sunglasses and a slight smile. He greeted them like old friends. Invited them in for beverages and shortly after showed them to the door, wishing them both all the best. Camille never saw him again. Christa reunited with this stranger three decades later and asked him if he was her father, and he replied, “I suppose so,” to which she said, “I’m glad we got that squared away.”IIWas it in this moment that Camille decided to abandon motherhood? Or was it many moments that led to her dropping Christa off and speeding away? Christa, along with Camille’s family, believe it was an affair she was having with a White man named James Hatch. Her stepsister Josie was his student at UCLA in the theater department in 1959, and she introduced Camille and Jim. Knowing that Camille was single, she said, “He’s ready.” Camille was teaching then in the public school system and making ceramics at home. She asked Hatch to come over and take a look at her pots and he asked her to audition for a play he cowrote with UCLA colleague C. Bernard Jackson inspired by the Greensboro, North Carolina, student sit-ins, Fly Blackbird. She was never quite as good at acting as she had hoped and was selected for the chorus, but she was onstage at the Metropolitan Theater in LA. Jim was the first person to tell Camille she was a good artist. “I will always love him for that,” she says. His support provided her with permission to be whoever she pleased in any given moment, even if that meant not being pretty, what her family said a woman must be at all costs. This introduced Camille to a new way of being. A world of artists and activists, organized by the American Civil Liberties Union, who began protesting school segregation and Black oppression. At the height of the Civil Rights Movement, Camille was the mistress of a White man who believed in her, and despite Los Angeles being on the precipice of the Watts Uprising, she was not deterred by the vile language and glares thrown at them by strangers. Camille began slowly shedding the cultural influences of middle-class Black America. Her parents had come to California during the Great Migration, like many Southern Blacks who moved west in search of opportunity and the possibility of providing their family with security from the violence inflicted on Black bodies. In LA they worked in service to White folks, therefore it wasn’t necessarily work that they couldn’t attain in the South, it was their dignity. Her father, Luscious, from Texas, was a cook and her mother, Alma, from South Carolina, was a domestic and seamstress. However, escaping the South in physicality doesn’t remove the emotional traumas of being Black in America; their White ideals were held firmly intact and their Southern traditions folded neatly within. Whiteness was still seen as superior in eloquence and refinement and the Billopses would emulate this in their home, for appearances’ sake, but when the burlap curtains closed at night, Luscious drank like a fish until he passed out and his wife carried him to bed each night. Alma bestowed these beliefs of Black female servitude on her two daughters, and they consented, but the youngest child will always rebel, and for Camille, Jim was the catalyst. She had been taught that motherhood and womanhood were inextricable. If you were not a mother, then what would you be? Mother is to be a woman’s highest title, and anything that takes precedence, even your own dream, is deemed selfish. Images of Camille with baby Christa show a polished and respectable young lady with permed hair and slicked-down edges. But in the images with Jim, you can see the physical transformation. She cuts off her permed roller set curls and has a small perfectly picked Afro. The hairs along her top lip thicken and grow wildly, untamed. Camille preferred to be called artist, not mama. She had never allowed Christa to call her Mama, she was to call her Bootsie, like all of her closest friends and family. Jim also suspected that Camille was giving up Christa for him and offered just enough discouragement to absolve himself of responsibility, “Don’t give Christa up for me.” When Jim was offered a Fulbright appointment to teach at the High Institute of Cinema in Cairo, Egypt, the center of the 1960s Pan-African movement that brought over many young American artists and activists like Maya Angelou and Malcolm X, he asked Camille to come visit before his wife and kids arrived, and without hesitation she went. But before departing Cairo, she told him she would not return unless he left his wife and children. “He met me at the airport and his wife left,” she says, “we chose each other and entered into another life. That’s when the world opened.”In Cairo, Camille began experimenting with sculpture and her first solo exhibition at Gallerie Akhenaton was a small collection of ceramic pots and sculptures of those close to her, like Jim, who would serve as her constant muse, benefactor, and advocate. Their intimacy and artistry were to always exist intertwined given the racially charged political unrest that they protested in their life and through their creations. They dared to love each other in a time when interracial relationships were still considered criminal in the United States. Their first collaboration was a book of poetry called Poems for Niggers and Crackers, published in Cairo in 1965, with poems written by Jim and American poet Ibrahim Ibn Ismail; Camille created the illustrations. Driven by all that she had sacrificed, Camille explored any medium she could get her hands on, photography, painting, printmaking, and eventually film, which would be her most critically acclaimed work. She spent many years creating and showing work in Egypt, Germany, and China before returning to her homeland after John F. Kennedy’s assassination, to find her own countrymen not so welcoming to Black women artists. They settled into New York City’s East Village where the Armenian American English professor and author Leo Hamalian helped Jim secure a teaching position in theater at City College while Camille taught ceramics there. As with all great artists, there comes a time when you must turn inward and begin dissecting yourself, to become the subject of your own examination. This led Camille into filmmaking.IIICamille tells me:“I was with all of the various Nigga bitches. Emma Amos, Faith Ringgold, Elizabeth Catlett. They had Black night at museums like the Whitney where they would let us in the building but not show our work. We were fighting so hard to get into the Brooklyn Museum and they wouldn’t let us in. So we said, well fuck you and the horse you rode in on. I said, you know what, I’m making my own way. So we bought this big-ass loft a long time ago when it was cheap. I told Jim, why don’t we buy a loft, and we did it. Jim had most of the money. I had a little something to contribute. I told him I wanted my name on it, and he said okay, so we got married. We are all we have. I would have never ended up being a working artist if it weren’t for him. His favorite words were ‘Why not?’ and ‘Yes you can.’ We created a library space, a studio in the back, an archive, and the dining area is where we host salons for our publication Artist and Influence. Every Black artist of our time has sat right here in this living room, and we recorded it all—bell hooks, Julie Dash, Amiri Baraka, all the Niggas. We invited everybody here: friends, students, and White gallerists and curators. We sold art right off our walls. I stopped begging a long time ago when I discovered I could sell art without having to kiss booty. These alternatives made it possible. Bob Blackburn was very helpful, he taught me printmaking. There were many artists that I met at the print shop while I was working, like Romi [Romare Bearden]. This is what you do when people don’t let you into their playground. We did it out of defiance. I always did whatever I wanted to do.“In the early ’80s Christa found me. It was a great shock to me. She sent a letter and a cassette tape with a song, asking me if I would see her. She was twenty-something. I was scared because I had already learned how to live with my guilt about giving her up. I wasn’t trying to come out from beneath the water. I was never a very good mother. I did what was best for both of us. I was twenty-three and I hardly saw her when she was little, she was always with my sister Billie or my mama. Mothers are supposed to protect, and the only way I could do that was by giving her up. I didn’t see this as feminist then, I just knew I wanted to reverse it, I wanted to be free of motherhood. I agreed to meet with her. Jim really liked her, and they got on. Naturally, she was an artist like me, it’s in her blood. When I started making films, she helped us. You can hear her voice singing on the opening scene of Suzanne, Suzanne about my niece’s drug addiction and her abusive father. People wasn’t talking about domestic violence back then. Our films had a tendency toward dirty laundry, they say it like it is, not like it’s supposed to be. It was hard enough being Black so everyone wanted to appear perfect, keep up appearances, you know. My sister wanted to take Christa but I didn’t trust my brother-in-law, Suzanne’s father. Her adopted mother, Margaret, was fabulous, a jazz singer. She was the little ship that helped me sail the dangerous night. Then we made the film Finding Christa. Christa stayed here with us for a while when we were making the film and then she moved to New York to study, so I could help her become a singer. We were always fighting because she wanted me to feel guilty. She kept asking me why I gave her away. It was always verbally violent, and guilt-ridden. I was all kinds of bitches to her. She wasn’t easy. I tried to explain to her that I didn’t want to be a mother. But it was complicated. Jim says we were too much alike. She’s a Sagittarius and I’m a Leo, too much fire. She was a star in Finding Christa. People say I show no remorse in the film, they say I’m cold, but if I had to do it again I would. I know I made the right decision, wouldn’t change a thing. Well, the only thing I would do differently would be to give her up earlier. But it was hard. Her father disappearing on me was a gift, otherwise if he had stayed, I would have just endured, that’s what Black women did in my family, endured. Christa was a very good actress, and this was a part of our competitiveness. She took up space in a way that was threatening to me. This caused a big friction when she was staying with us. Adoptees have what they call ‘the great wound,’ and it would always come back to, ‘Why did you throw me away?’ She would come and stay here and see everything that we have built and turn to me and ask, ‘Why wasn’t I here? Why wasn’t I a part of this?’ Jim welcomed her with open arms. But I didn’t like her taking up so much space here. I would correct her and let her know, ‘This ain’t your place. You don’t own this.’ She was even beginning to claim the film, saying it was her film. I said, ‘Now wait a minute, you didn’t shoot that film. I shot that film. I cut that film.’ She wanted to be a filmmaker but want and spit are two different things. Yeah, so I suppose there was some essence of competitiveness. She was difficult, I was difficult. We had an argument and then she walked out one day. Then one day she returned. It didn’t last. It became argumentative again. Then she left again in 2013. We didn’t talk again. I let it go. She had become ill and had to have an operation. Then she needed another one and she said she wouldn’t have it. She killed herself by not taking that operation. I wasn’t invited to the funeral. When she died somebody called to tell me. Who was it that called me? I don’t remember. It was early in the morning. Like a blast from the furnace. You have to stand very still and face it. Then I had to bury it. Jim and I both. And that was it. It has to have a place. I’ve accepted the guilt. I will carry it with me forever. Sometimes I feel her when I am working.”IVBefore Christa’s death she shared a letter on her Facebook page in 2014 titled “Given up Twice—Is It All Worth It?” In the letter she speaks about calling her stepfather, Jim, on Father’s Day 2013 and Camille also picking up a receiver in a different room and abruptly hanging up when Christa announced herself. Half an hour after the call Christa receives an email from Jim stating that she should never call or visit their home again. Christa suspects that this email was written by Camille, as it contains a “callous” brashness that isn’t indicative of Jim’s character toward her. The email stated that both Jim and Camille were “cutting all communications” with her, including “telephone, letters, on the internet and personal appearances on the tai chi court,” as she was causing too many disruptions in their lives. The email was signed by Jim and sent from his account, but the statement “four-year-old child continues to protest her mother’s decision for giving her up” were words that she had heard endlessly from her biological mother. Christa never spoke to Camille again, but after seeing a therapist, she concluded that Camille was uncomfortable with Christa’s intimate relationship with Jim. Thirty-two years after reuniting, Christa was dismissed. This three-thousand-word letter is filled with discreet anger, confusion, hurt that reads like a muffled scream into the abyss of social media. She signed the letter, “Christa Victoria (my name since birth).”In the film Finding Christa, which won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance, making Camille the first Black woman producer/director to be awarded this prize, Christa says that she felt like an octopus, wanting to extend all parts of herself around the woman who birthed her, but Camille felt like a cactus, sharp and defensive. Christa also states that meeting her birth mother and biological family saved her life, but one may consider their final split to be the event that led to her demise. Camille challenged assumptions about what a Black middle-class woman had to be and chose her artistry above all else; despite her family’s beliefs that she chose Jim, she was choosing herself. To assume that Camille prioritized her relationship with her life partner seems misplaced and in contradiction to her radical act, which was to choose herself even when everything around her said that her purpose was to serve, soothe, and comfort, a rejection to the concept of Mammy. Camille’s genius lay in her ability to imagine Black futures in a country that did not value Black life and the expression of that life through art. Before Roe v. Wade, before the Loving v. Virginia ruling, she made decisions that seemed improbable.The future that Camille envisioned was one that benefited the well-being and advancement of not just one individual being that she birthed but an entire generation of artists and scholars who were nourished by her contributions as an artist and archivist. Christa, unfortunately, was a casualty in Camille’s ambitious defiance."

}

,

"relatedposts": [

{

"title" : "To Grieve Together Is to Heal Together: Rituals of Care In Minneapolis",

"author" : "Joi Lee",

"category" : "essays",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/healing-rituals-minneapolis",

"date" : "2026-02-20 08:48:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/Lee_Minn_Image1.jpeg",

"excerpt" : "",

"content" : "Signs of resistance and community solidarity are found on every block, in every neighborhood. This is a sign a few houses down from Renee Good’s memorial. Photo Credit: Joi LeeOver the last three months, the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minn. have lived under siege. On December 4, 2025, the Department of Homeland Security announced the start of Operation Metro Surge as part of Trump’s crackdown on immigration. Around 3,000 immigration agents flooded into the region, turning Minneapolis into the epicenter for what would become the largest immigration enforcement operation in United States history.Neighbors watched other neighbors being abducted. The shrill sound of whistles—the warning sign that ICE was nearby—became the all-too-familiar soundtrack to the city. Streets, and the businesses that lined them, once bustling, became quiet, threatening the many diverse communities that form the cultural backbone of the Twin Cities: Somali, Hmong, Latine, among others.And then, on January 7, Renee Good, an everyday Minnesotan who was watching out for her neighbors, a legal observer, was shot and killed. Seventeen days later, Alex Pretti, an ICU Nurse, met the same fate at the hands of ICE officers.What followed made international headlines: civilians clashing with federal agents as flash bangs, tear gas, and rubber bullets filled the streets of Minneapolis. Images of confrontation traveled far beyond the city, flattening a much more complicated reality unfolding on the ground—as the news cycle has done repeatedly to Minneapolis over the years with the murders of Jamar Clarke in 2014, Philando Castile in 2016, and George Floyd in 2020 at the hands of police brutality.As tensions threatened to spiral further, the Trump administration announced a series of changes: replacing ICE commander Greg Bovino with so-called “border czar” Tom Homan, and on February 12, announcing that the operation in Minneapolis would come to an end. But in Minneapolis, many residents say the shift has been more cosmetic than substantive. Raids continue, surveillance lingers, and entire communities remain on edge.The fear has not lifted. It has settled.In this fragile uncertainty of what happens next, the Minneapolis community has turned to care. Across the city, people are gathering not just to strategize or protest, but to also grieve together: to light candles, pray, sing, and move their bodies in unison. Memorials for Good and Pretti have become meeting grounds. Healing circles, ceremonies, and music-filled vigils have emerged as lifelines for a community nowhere near recovered, yet refusing to unravel.Posters of Renee Good and Alex Pretti adorn the city, plastered on empty walls, hung up on store windows. Photo Credit: Joi LeeA legacy of trauma—and healingIn Minneapolis, trauma does not arrive without memory. Neither does healing.I met Leslie Redmond, an organizer and former president of Minneapolis NAACP, at a healing circle she convened the day after Pretti’s murder. Nestled in a small community cafe, tables were pushed aside and chairs brought into the circle. Wafts of warm home-made chili floated in from the vegan kitchen, and cups of piping hot lemon ginger tea—nourishing for the soul, we were assured—were handed out.As folks trickled into their seats, nervous chatter gave way to quiet realization that everyone was holding a pain that needed to be shared. Looking around the faces in the room, many etched with stress and exhaustion, Redmond reminded us, “Before we can build, we must heal.”Redmond is no stranger to collective trauma inflicted by the hands of law enforcement. She had lived through the police killings of Jamar Clarke, Philando Castile, and George Floyd, as well as the uprisings that followed.“Back then, I wasn’t actively healing. My back went out. My hair was falling out. We were in the fight phase. And then I realized, we need to move to the healing phase.”By the end of 2020, Redmond decided to create a community healing team for collective mourning. When Good was killed, that infrastructure, built slowly and deliberately, was ready to spring into action.“Healing is fundamental,” Redmond said, before quoting Audre Lorde’s seminal words from A Burst of Light: “Self-care is not self-indulgence. Self-care is self-preservation, which is an act of political warfare.”These days, Remond facilitates weekly healing circles. For many, the healing circles have become a place to reset. To find solace in knowing that what Minnesotans are going through is real, and not imagined. To find validation in their pain, yet also resolution in how to move forward. At one of the meetings, a 13-year-old quietly confessed to the group, “I feel like I’ve lost my peace.” At another, a Somali elder shared, “We’ve been living in fear. But looking around, how beautiful to remember why I decided to call this place my home.”Different cultures, shared medicine in memorialThe memorials of Pretti and Good, built at the sites where they were killed, have become living spaces of ceremony and connection. The rituals of healing are as diverse as the communities that Pretti and Good gave their lives to protect. At a vigil for Pretti organized by his fellow nurses, I met members of the Hmong community, an ethnic group that originates from Southeast Asia and largely came over as refugees to Minneapolis in the mid-1970’s. The Twin Cities are home to the largest concentration of Hmong people in the U.S.One person held a sign reading, “A Hmong shaman for healers & humanity!” Another read, “A Hmong Christian for healers & humanity!”A woman who asked me to call her Yaya explained why she was there. “As a healer from the Hmong community, as a shaman, I came to support them, healer to healer,” she said. “Because we do so much healing, but we forget to heal ourselves. Today is about healing the healers.”The group offered both prayers and blessed strings. People approached quietly, asking for care. Some requested Christian prayer, others a shamanic blessing. Kiki, the Christian, clasped their hands tightly, offering a prayer and a hug. Yaya took each person’s right hand, looping a thin string around the wrist and tying it gently in place, murmuring a prayer so soft it barely rose above the street noise.Many accepted both.Ceremony as resistanceIndigenous communities also organized ceremonies honoring Good and Pretti.Among them was a Jingle Dress Dance ceremony, rooted in Ojibwe healing traditions, meant to restore health and balance to those who need it. Over 30 members of the Minneapolis Native community came together at both memorials to perform their sacred dance, adorned in vibrant dresses. Metal cones are woven in intricate patterns around the dress, such that a slight movement creates a rhythmic sound.“The dress came to our people when there was a time of sickness. And so that’s what we do. We show up when there’s people suffering,” Downwind said, one of the organizers of the ceremony.Jingle Dress Dancers gather at Renee Good memorial’s site to perform a healing ceremony. Photo Credit: Joi LeeThe sound of metal cones sewn onto the dresses echoed through the cold air—each step a prayer, each movement an offering—was met with quiet attentiveness by the audience.When the dance finished at Good’s memorial, the crowd moved to Pretti’s, a journey that in itself felt like a pilgrimage, connecting the deaths of two Minnesotans with the lives of all those who remained, continuing their legacy.For many in attendance, the presence of Native dancers felt both sacred and a reminder that this land holds older traditions of survival. That healing did not begin, nor will it end, with this moment.**Music and the permission to feel **Music has also become a vessel for collective healing. Groups like Brass Solidarity,a band that was founded in response to the murder of George Floyd, have organized performances at the memorials, bringing instruments into spaces thick with grief.In the cold, unforgiving nights of Minneapolis, hundreds gather by Alex Pretti’s memorial site to listen to the musical tribute given by Brass Solidarity. Photo Credit: Joi LeeOne evening at Pretti’s memorial, hundreds of people stood shoulder to shoulder, bodies seeking warmth and rhythm. Brass instruments rang out, fingers braving subzero temperatures to play. Anthony Afful, a musician with Brass Solidarity, described the role of music in these spaces. “Part of what we’re doing,” he said, “is helping people remember that they’re human.”Music, he explained, creates room for the full range of emotion. “This is a dark time. There has to be space for grief, for rage, and also for joy—to exist together.”I spoke to another musician, Tufawon, who is Native-Boricua. For him, it is not just experiencing music but also its creative expression that helps unlock emotional processing. He’s currently holding a music workshop for Native youth, many of whom have been deeply impacted by ICE raids despite being the Indigenous peoples of this land.“As colonized people, we’re impacted by historical trauma,” Tufawon explained. “We carry it through our genes. And now there’s a collective trauma that the entire city, the entire state, really, is holding. We don’t take the time to process what we experience. Music is a mindfulness practice. So I use music to bring healing into the moment, so they can find some level of balance and not crash so hard when it’s all over.”Tufawon is a local Minneapolis artist, both Native and Puerto Rican, who uses music as an educational and community tool to heal and lift up the Native youth community. Photo Credit: Joi LeeHealing circles, ceremonies, music, and prayer: many of these are rituals with a rich, long history. They have navigated many cultures in the past and will continue to do so in the future.They have passed through countless cultures and generations, carrying meaning far beyond any single moment.But in a time where Minneapolis is being ripped apart—when the very definition of who belongs, of what it means to be an “American,” is under violent scrutiny—these rituals of care have reaffirmed something that cannot be detained, erased, or deported. That the very fabric of this place has been woven together by so many cultures, by so many peoples. And that it will be healed by them, together.Minneapolis is no stranger to rebuilding. It is a city, a sacred land, that is practiced in rising from devastation, again and again."

}

,

{

"title" : "aja monet’s new single: “hollyweird”",

"author" : "aja monet",

"category" : "visual",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/aja-monet-hollyweird-release",

"date" : "2026-02-19 05:00:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/aja-monet---Hollyweird-_-Single-Art.jpg",

"excerpt" : "Surrealist blues poet aja monet shares her first new music since 2024 with the release of her timely new single “hollyweird” via drink sum wtr. The track, produced by monet, Meshell Ndegeocello and Justin Brown, arrives with a bold video directed by B+ and Monet herself, and features Chicago rapper and close collaborator, Vic Mensa.",

"content" : "Surrealist blues poet aja monet shares her first new music since 2024 with the release of her timely new single “hollyweird” via drink sum wtr. The track, produced by monet, Meshell Ndegeocello and Justin Brown, arrives with a bold video directed by B+ and Monet herself, and features Chicago rapper and close collaborator, Vic Mensa.“I wrote ‘hollyweird’ on scraps of found paper, frantically jotting down observations and sentiments of the moment during the Los Angeles fires and its aftermath,” monet explains. “The song is an Afropunkesque ode to frustrations and feelings around our current culture of social isolation and performative solidarity. I wanted to speak to the emptiness of ‘hollyweird’ not as a place but as a way of being where insincerity is normalized. Where social interactions become void in of sincerity and we lose sight of community and connection.”“hollyweird” is the first taste of new music from monet since the release of her debut album, when the poems do what they do, in 2023. The album was released by drink sum wtr to wide critical praise and was nominated at the 66th GRAMMY Awards for Best Spoken Word Poetry Album in 2024. The album marked the arrival of a singular poet and peerless lyricist. On it, monet explored themes of resistance, love, and the inexhaustible quest for joy.monet is bringing her singular live show to New York City’s famed Carnegie Hall Theater. The show will take place at the Zankel Hall on May 20th.Get the track on all digital platforms here"

}

,

{

"title" : "How to Resist “Organized Loneliness”: resisting isolation in the age of digital authoritarianism ",

"author" : "Emma Cieslik",

"category" : "essays",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/how-to-resist-organized-loneliness",

"date" : "2026-02-13 15:11:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/American_protesters_in_front_of_White_House-11.jpg",

"excerpt" : "Over the past year, many of us have encountered, navigated, and processed violence alone on our phones. We watched videos of Renee Nicole Good and Alex Pretti being fatally shot and Liam Conejo Ramos being detained by ICE agents. These photos and videos triggered anger, sadness, and desperation for many (along with frustration that these deaths were the inciting blow against ICE agents that have killed many more people of color this year and last).",

"content" : "Over the past year, many of us have encountered, navigated, and processed violence alone on our phones. We watched videos of Renee Nicole Good and Alex Pretti being fatally shot and Liam Conejo Ramos being detained by ICE agents. These photos and videos triggered anger, sadness, and desperation for many (along with frustration that these deaths were the inciting blow against ICE agents that have killed many more people of color this year and last).While the institutions and people committing these crimes do not want them recorded, the Department of Homeland Security and the wider Trump administration is using “organized loneliness,” a totalitarian tool that seeks to distort peoples’ perception of reality. Although seemingly a symptom of COVID-19 pandemic isolation and living in a more social media focused world, “organized loneliness” is being weaponized to change the way people not only engage with violence but respond to it online, simultaneously desensitizing us to bodily trauma and escalating radicalization and recruitment online.Back in 2022, philosopher Samantha Rose Hill argued that the loneliness epidemic sparked by the COVID-19 pandemic could and would have dangerous consequences. She specifically cites Hannah Arendt’s 1951 book The Origins of Totalitarianism, which argued that authoritarian leaders like Hitler and Stalin weaponized people’s loneliness to exert control over them. Arendt was a Jewish woman who barely escaped Nazi Germany.As Hill told Steve Paulson for “To The Best Of Our Knowledge,” “the organized loneliness that underlies totalitarian movements destroys people’s relationship to reality. Their political propaganda makes it difficult for people to trust their own opinions and perceptions of reality.” Because as Arendt wrote, “the ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction and the distinction between true and false no longer exist.”While this piece grounds discussions of organized loneliness in Arendt’s work, Black feminist scholars and organizers have long called out how isolation, state-sanctioned surveillance, and fragmentation are functions of racialized and gender-based control. bell hook’s writings about forced isolation cemented by individualism and materialism in All About Love: New Visions and Audre Lorde’s discussions of fragmentation of the mind from the body and self from community assert that “organized loneliness” is not new in the United States. Loneliness has long been used as a weapon of the American state to assert emotional, political, and structural control by keeping up separated. This piece, and modern reflections on “organized loneliness” is built on the foundation of Black feminist scholars like hooks, Lorde, and Angela Davis; they were some of the first to name “organized loneliness” along with Arendt.But there are ways in which we can resist the threat that “organized loneliness” represents, especially in the age of social media. They include acknowledging this campaign of loneliness, taking proactive steps when engaging with others online, and fostering relationships with friends and our communities to stand in solidarity amidst the rise of fascism.1. The first step is accepting that loneliness affects everyone and can be exploited by authoritarian movements.Many of us know this intimately. Back in 2023, the U.S. Surgeon General flagged an already dire loneliness epidemic, that in combination with a transition of most interaction onto social media, changes the way in which we engage with violence and tragedy online. But it can be hard to admit that loneliness affects us, especially when we are constantly connected through social media. It’s important to admit that even for the most digitally literate and active among us, “organized loneliness” not only can occur but especially occurs on social media.Being susceptible to or affected by “organized loneliness” is not a moral shortcoming or a personal failure but acknowledging it and taking steps to connect with one another is the one way we resist totalitarian regimes.2. Next, take social media breaks–and avoid doomscrooling.Even before the advent of social media or online news outlets, Arendt was warning about how loneliness can become a breeding ground for downward spirals. She explains that the constant consumption of tragic, violent, and deeply upsetting news–and watching it unfold in front of us can not only be overstimulating but can desensitize us and disconnect us from reality.While it can be difficult when most of our social lives exist on social media (this will be unpacked later), experts recommend that people limit using social media to less than two hours per day and avoid using it during the first hour after waking up and the last hour before going to sleep. People can use apps that limit overall screen time or restrict access to social media at set times–the best being Opal, One Sec, Forest, and StayFree. People can also use these apps to limit access to specific websites that might include triggering news.But it’s important to recognize that avoiding doomscrooling does not give people license not to stay informed or to look away from atrocities that are not affecting their communities.3. Resist social media echo-chambers by diversifying your algorithm.When you are on social media, however, it’s important to recognize that AI-based algorithms track what we engage with and show us similar content. People can use a VPN to search without creating a record that AI can track and thus offer us like offerings, but while the most pronounced (and reported on) examples focus on White, cis straight men and the Manoverse, echochambers can affect all of us and shift our perception of publicly shared beliefs.People can resist echo-chambers by seeking out new sources and accounts that offer different, fact-based perspectives but also acknowledge their commitment to resisting fascism, such as Ground News, ProPublica, and Truthout. Another idea is to follow anti-fascist online educators like Saffana Monajed who promote and share lessons for media literacy. People can also do this by cultivating their intellectual humility, or the recognition that your awareness has limits based largely on your own experiences and privileges and your beliefs could be wrong. Fearless Culture Design has some great tips.While encountering and engaging different perspectives is vital to resisting echochambers and social algorithms, this is not an invitation to follow or platform any news outlet, content creator, or commentator that denies your or other people’s personhood.4. Cultivate your friendships and make new ones.In a time when many of us only stay in contact with friends through social media, friendships are more important than ever. Try, if you can, to engage friends outside of social media–whether it’s through in-person meet ups (dinners, parties, game nights) or on digital platforms that are not social media-based, for example coordinating meet-ups over Zoom or Skype. This can be a virtual D&D campaign, craft circle, or a virtual book club. While these may seem like silly events throughout the week, they help build real connection.It’s important to connect with people outside of a space that uses an algorithm to design content and to reinforce that people are three-dimensional (not just a two-dimensional representation of a social media profile). There are even some apps that assist with this goal, such as Connect, a web app designed by MIT graduate students Mohammad Ghassemi and Tuka Al Hanai to bring students from diverse backgrounds together for lunch conversations.Arendt writes that totalitarian domination destroys not only political life but also private life as well. Cultivating friendships–and relationships of solidarity with your neighbors and fellow community members–are the ways in which we not only resist the destruction of private relationships but also reinforce that we and others belong in our communities–and that we can achieve great things when we stand together!5. With this in mind, practice intentional solidarity with one another.While it’s likely no surprise, fascism functions to both establish a nationalist identity that breeds extremism and destroy unification and rebellion against authority. The best way to resist the isolation that totalitarian governments breed is to practice intentional acts of solidarity with marginalized communities, especially communities facing systemic violence at the hands of an authoritarian power.Writer and advocate Deepa Iyer discusses the importance of action-based solidarity in her program Solidarity Is, part of the Building Movement Project, and Solidarity Is This Podcast (co-hosted with Adaku Utah) discusses and models a solidarity journey that foregrounds marginalized communities. I highly recommend reading her Solidarity Is Practice Guide and the Solidarity Syllabus, a blog series that Iyer just started this month to highlight lessons, resources, and ideas of how to cultivate solidarity within your own communities.6. Consume locally and ethically, and reject capitalist productivity.And one way that people can stand in solidarity with their communities is to support local small businesses that invest back into the communities. When totalitarianism strips people of many platforms to voice concern, one of the last remaining power people have is how and where they spend their money. Often, this is what draws the most attention and impact, so it’s important to buy (and sell) based on Iyer’s Solidarity Stances and to also resist the ways in which productivity culture not only disempowers community but devalues human labor.At the heart of Arendt’s criticism of totalitarian domination is the ways in which capitalism, a “tyranny over ‘laborers,’” contributes to loneliness itself (pg. 476). Whether intentional or not, this connects to modern campaigns not only of malicious compliance but also purposeful obstinance in which people refuse to labor for a fascist regime but to mobilize their ability to labor as a form of resistance–thinking about the recent walkouts and boycotts that resist by weaponizing our labor and our spending power.Not only should people resist the conflation of a person’s value to their productivity, but they should use their labor–and the economic products of it–as tools of resistance in capitalism.Thankfully as Arendy writes, “totalitarian domination, like tyranny, bears the germs of its own destruction,” so totalitarianism by definition cannot succeed just as humans cannot thrive under the pressure of “organized loneliness.” For this reason, it’s a challenge to hold on and resist the administration using disconnection to garner support for the dehumanization of and violence against human beings. But as long as we do, we have the most powerful tools of resistance–awareness, friendship, community, and solidarity–at our disposal to undo totalitarianism just as it was undone back in the 1940s."

}

]

}