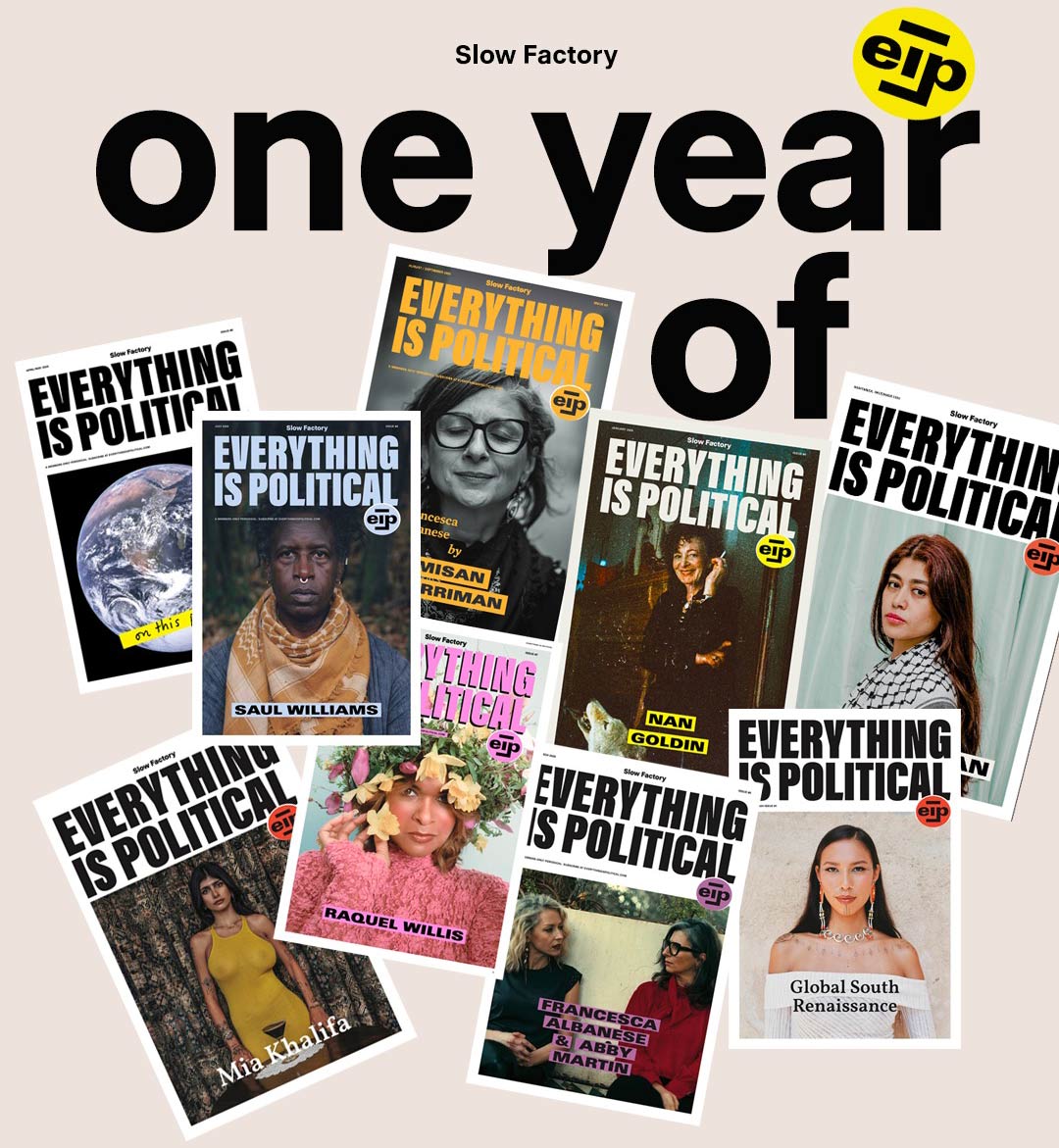

Digital & Print Membership

Yearly + Receive 8 free printed back issues

$420 Annually

Monthly + Receive 3 free printed back issues

$40 Monthly

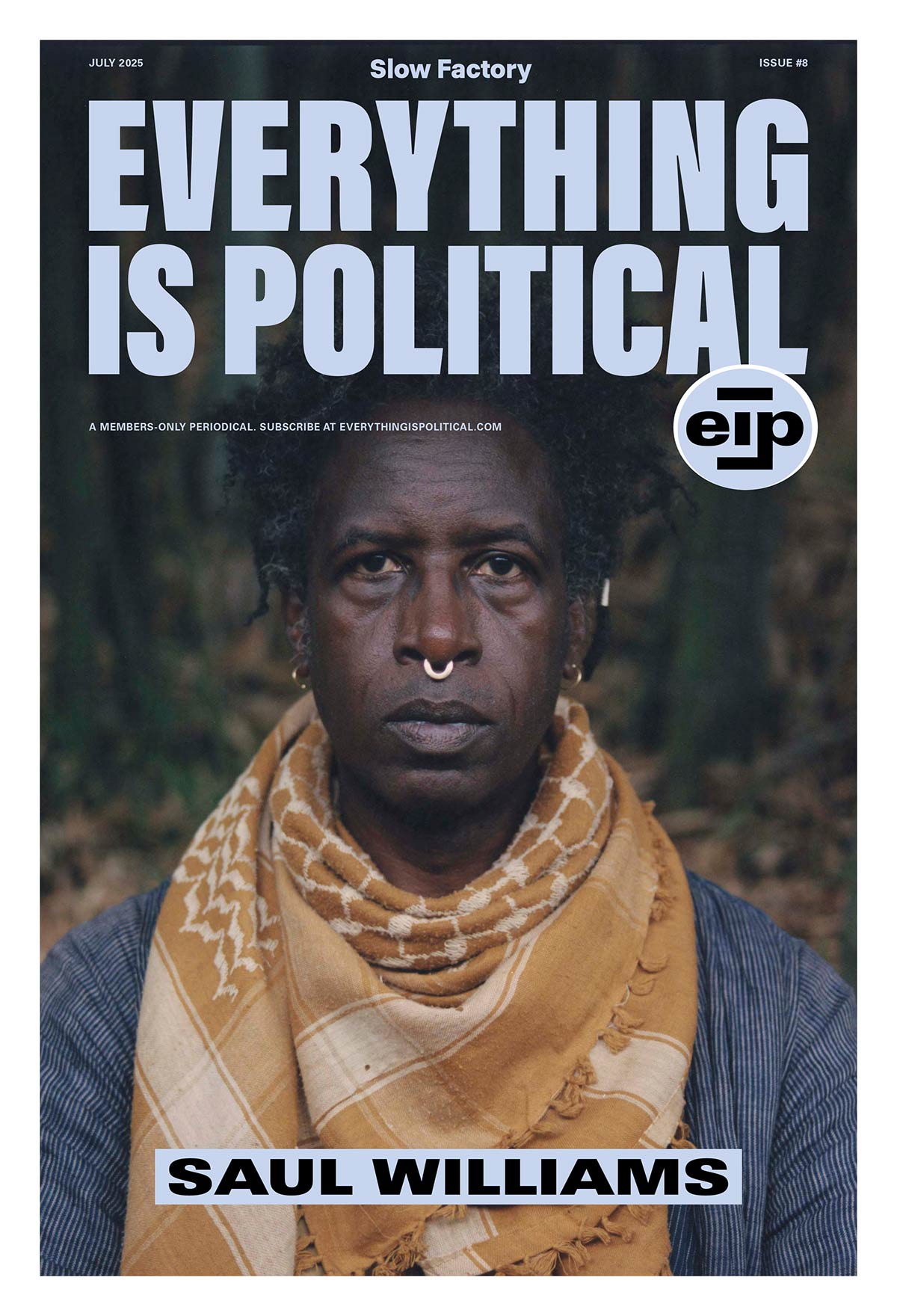

Saul Williams

Nothing is Just a Song

Collis Browne: Is all music and art really political?

Saul Williams: Many artists would like to believe that there is some sort of sublime neutrality that art can deliver, that it is beyond or above the idea of politics. However, art is sometimes used as a tool of Empire, and if we are not careful, then our art is used as propaganda, and thus, it becomes essential for us to arm our art with our viewpoints, with our perspective, so that it cannot be misused. I have always operated from the position that all my work carries politics in it, that there are politics embedded in it. And I’ve never really understood, if you are aiming to be an artist, why you wouldn’t aim to speak directly to the times. Addressing the political doesn’t have to take away from the personal intimacy of your work.

Even now, we are reading the writings of Palestinian poets in Gaza and the West Bank, not to mention those who are part of the diaspora, who are charting their feelings and intimate experiences while living through a genocide. These works of art are all politically charged because they are charged with a reality that is fully suppressed by oppressive networks and powers that control them.

Shakespeare’s work was always political. He found a way to speak about power to the face of power, knowing they would be in the audience. But also found a way to play with and talk to the “groundlings,” the common people who were in the audience as well.

Collis Browne: Was there a moment when you realized that your music could be used as a tool of resistance?

Saul Williams: Yeah, I was in third grade, about eight or nine years old. I had been cast in a play in my elementary school. I loved the process of not only performing, but of sitting around the table and breaking down what the language meant and what the objective and the psychology of the character was, and what that meant during the time it was written. I came home and told my parents that I wanted to be an actor when I grew up. My father had the typical response: “I’ll support you as an actor if you get a law degree.” My mother responded by saying, “You should do your next school report on Paul Robeson, he was an actor and a lawyer.”

So I did my next school report on Paul Robeson. And what I discovered was that here was an African American man, born in 1898, who had come to an early realization as an actor that the messages of the films he was being cast in—and he was a huge star—went against his own beliefs, his own anti-colonial and anti-imperial beliefs. In the 1930s, he started talking about why we needed to invest in independent cinema. In 1949, during the McCarthy era, he had his passport taken from him so he could no longer travel outside of the US, because he refused to acknowledge that the enemies of the US were his enemies as well. He felt there was no reason Black people should be signing up to fight for the US Empire when they were going home and getting lynched.

In 1951, he presented a mandate to the UN called “We Charge Genocide.” In it he charged the US Government with the genocide of African Americans because of the white mobs who were lynching Black Americans on a regular basis. [Editor’s note: the petition charges the US Government with genocide through the endorsement of both racism and “monopoly capitalism,” without which “the persistent, constant, widespread, institutionalized commission of the crime of genocide would be impossible.”] When Robeson met with President Truman, Truman said, “I’d like to respond, but there’s an election coming up, so I have to be careful.”

Paul Robeson sang songs of working-class people, songs that trade unionists sang, songs that miners sang, songs that all types of workers sang across the world. He identified with the workers and with the working class, regardless of his fame. He was ridiculed by the American Government and even had his passport revoked for his activism. At that early age, I learned that you could sing songs that could get you labeled as an enemy of the state.

I grew up in Newburgh, New York, which is about an hour upstate from New York City. One of my neighbors would often come sing at my father’s church. At the time, I did not understand why my dad would allow this white guy with his guitar or banjo to come sing at our church when we had an amazing gospel choir. I couldn’t understand why we were singing these school songs with this dude. When I finally asked my parents, they said, “You have to understand that Pete—they were talking about Pete Seeger—is responsible for popularizing some of the songs you sing in school.” He wrote songs like “If I Had a Hammer,” and he too was blacklisted by the US government because of the songs he chose to sing and the people he chose to sing them for, and the people he chose to sing them with. I learned at a very early age that music and art were full of politics. Enough politics to get you labeled as the enemy of the state. Enough politics to get your passport taken, or to be imprisoned.

I was also learning about my parents’ peers, artists whom they loved and adored. Artists like Sonia Sanchez, Amiri Baraka, and Nikki Giovanni, all from the Black Arts Movement. Larry Neal and Amiri Baraka made a statement when they started the Black Arts Repertory Theatre School in Harlem that said essentially that all art should serve a function, and that function should be to liberate Black minds.

It is from that movement that hip-hop was born. I was lucky enough to witness the birth of hip-hop. At first, it was playful, it was fun, but by the mid to late 1980s, it began finding its voice with groups like Public Enemy, KRS-One, Queen Latifa, Rakim, and the Jungle Brothers. These are groups that started using and expressing Black Liberation politics in the music, which uplifted it, made it sound better, and made it hit harder. The first gangster rap was that… when it was gangster, when it was directly challenging the country it was being born in.

As a teenager, I identified as a rapper and an actor. I would argue with school kids who insisted, “It’s not even music. They’re just talking.” I would have to defend hip-hop as music, sometimes even to my parents, who found the language crass. But when I played artists like KRS-One and Public Enemy for my parents, they said, “Oh, I see what they’re doing here.”

When Public Enemy rapped, “Elvis was a hero to most, But he never meant shit to me you see, Straight up racist that sucker was, Simple and plain, Motherfuck him and John Wayne, ‘Cause I’m Black and I’m proud, I’m ready and hyped plus I’m amped, Most of my heroes don’t appear on no stamps,” my parents were like Amen. They understood. They understood why I needed to blast that music in my room 24/7. They understood.

When the music spoke to me in that way, suddenly I could pull off moves on the dance floor like doing a flip that I couldn’t do before. That’s the power of music. That’s power embedded in music. That’s why Fela Kuti said that music is the weapon of the future. And, of course, there’s Nina Simone and Billie Holiday. What’s Billie Holiday’s most memorable song? “Strange Fruit.” That voice connected, was speaking directly to the times she was living in. It transcended the times, where to this day, when you hear this song and you understand that the “strange fruit” hanging from Southern trees are Black people who have been lynched, you understand how the power of the voice, when you connect it to something that is charged with the reality of the times, takes on a greater shape.

Collis Browne: Public Enemy broke open so much. I grew up in Toronto, in a mostly white community, but I was into some of the bigger American hip-hop acts who were coming out. Public Enemy rose to a new level. Before them, we were only connecting with punk and hardcore music as the music of rebellion.

Saul Williams: Public Enemy laid down the groundwork for what hip-hop is: “the voice of the voiceless.” It was only after Public Enemy that you saw the emergence of huge groups in France, Germany, Bulgaria, Egypt, and across the world. There were big acts before them. Run DMC, for instance, but when Public Enemy came out, marginalized groups heard their music and said, “That’s for us. Yes, that’s for us.” It was immediately understood as music of resistance.

Collis Browne: What have you seen or listened to out in the world that has a clear political goal, but has been appropriated and watered down?

Saul Williams: We can stay on Public Enemy for that. Under Secretary Blinken, Chuck D became a US Global Music Ambassador during the genocide in Gaza. There are photos of him standing beside Secretary Blinken, accepting that role, while understanding that the US has always used music as a cultural propaganda tool to express soft power. I remember learning about how the US uses this “soft power” when I was working in the mid-2000s with a Swiss composer, who has now passed, named Thomas Kessler. He wrote a symphony based on one of my books, Said the Shotgun to the Head, and we were performing it with the Cologne, Germany symphony orchestra, when I heard from the head of the orchestra that, in fact, their main financier was the US Government through the CIA.

During the Cold War, it was crucial for the American Government to put money into the arts throughout Western Europe to try to express this idea of “freedom,” as opposed to what was happening in the Eastern (Communist) Bloc. So it was a long time between when the US Government started enlisting musicians and other artists in their propaganda campaigns and when I encountered this information.

There’s a documentary called Soundtrack to a Coup d’État, which talks about how the US Government used (uses) music and musicians to co-opt movements and propagate the idea of American freedom and democracy outside the US in the hope of winning over the citizens of other countries without them even realizing that so much of that art is there to question the system itself, not to celebrate it. Unfortunately, there are situations in which an artist’s work is co-opted to be used as propaganda, and the artist buys into it. They become indoctrinated, and you realize that we’re all susceptible to the possibility of taking that bait.

In Conversation:

Photography by:

{

"article":

{

"title" : "Saul Williams: Nothing is Just a Song",

"author" : "Saul Williams, Collis Browne",

"category" : "interviews",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/saul-williams-interview",

"date" : "2025-07-21 21:35:46 -0400",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/EIP_SaulWilliams_Shot_7_0218.jpg",

"excerpt" : "Saul Williams: Many artists would like to believe that there is some sort of sublime neutrality that art can deliver, that it is beyond or above the idea of politics. However, art is sometimes used as a tool of Empire, and if we are not careful, then our art is used as propaganda, and thus, it becomes essential for us to arm our art with our viewpoints, with our perspective, so that it cannot be misused. I have always operated from the position that all my work carries politics in it, that there are politics embedded in it. And I’ve never really understood, if you are aiming to be an artist, why you wouldn’t aim to speak directly to the times. Addressing the political doesn’t have to take away from the personal intimacy of your work.",

"content" : "Collis Browne: Is all music and art really political?Saul Williams: Many artists would like to believe that there is some sort of sublime neutrality that art can deliver, that it is beyond or above the idea of politics. However, art is sometimes used as a tool of Empire, and if we are not careful, then our art is used as propaganda, and thus, it becomes essential for us to arm our art with our viewpoints, with our perspective, so that it cannot be misused. I have always operated from the position that all my work carries politics in it, that there are politics embedded in it. And I’ve never really understood, if you are aiming to be an artist, why you wouldn’t aim to speak directly to the times. Addressing the political doesn’t have to take away from the personal intimacy of your work.Even now, we are reading the writings of Palestinian poets in Gaza and the West Bank, not to mention those who are part of the diaspora, who are charting their feelings and intimate experiences while living through a genocide. These works of art are all politically charged because they are charged with a reality that is fully suppressed by oppressive networks and powers that control them.Shakespeare’s work was always political. He found a way to speak about power to the face of power, knowing they would be in the audience. But also found a way to play with and talk to the “groundlings,” the common people who were in the audience as well.Collis Browne: Was there a moment when you realized that your music could be used as a tool of resistance?Saul Williams: Yeah, I was in third grade, about eight or nine years old. I had been cast in a play in my elementary school. I loved the process of not only performing, but of sitting around the table and breaking down what the language meant and what the objective and the psychology of the character was, and what that meant during the time it was written. I came home and told my parents that I wanted to be an actor when I grew up. My father had the typical response: “I’ll support you as an actor if you get a law degree.” My mother responded by saying, “You should do your next school report on Paul Robeson, he was an actor and a lawyer.”So I did my next school report on Paul Robeson. And what I discovered was that here was an African American man, born in 1898, who had come to an early realization as an actor that the messages of the films he was being cast in—and he was a huge star—went against his own beliefs, his own anti-colonial and anti-imperial beliefs. In the 1930s, he started talking about why we needed to invest in independent cinema. In 1949, during the McCarthy era, he had his passport taken from him so he could no longer travel outside of the US, because he refused to acknowledge that the enemies of the US were his enemies as well. He felt there was no reason Black people should be signing up to fight for the US Empire when they were going home and getting lynched.In 1951, he presented a mandate to the UN called “We Charge Genocide.” In it he charged the US Government with the genocide of African Americans because of the white mobs who were lynching Black Americans on a regular basis. [Editor’s note: the petition charges the US Government with genocide through the endorsement of both racism and “monopoly capitalism,” without which “the persistent, constant, widespread, institutionalized commission of the crime of genocide would be impossible.”] When Robeson met with President Truman, Truman said, “I’d like to respond, but there’s an election coming up, so I have to be careful.”Paul Robeson sang songs of working-class people, songs that trade unionists sang, songs that miners sang, songs that all types of workers sang across the world. He identified with the workers and with the working class, regardless of his fame. He was ridiculed by the American Government and even had his passport revoked for his activism. At that early age, I learned that you could sing songs that could get you labeled as an enemy of the state.I grew up in Newburgh, New York, which is about an hour upstate from New York City. One of my neighbors would often come sing at my father’s church. At the time, I did not understand why my dad would allow this white guy with his guitar or banjo to come sing at our church when we had an amazing gospel choir. I couldn’t understand why we were singing these school songs with this dude. When I finally asked my parents, they said, “You have to understand that Pete—they were talking about Pete Seeger—is responsible for popularizing some of the songs you sing in school.” He wrote songs like “If I Had a Hammer,” and he too was blacklisted by the US government because of the songs he chose to sing and the people he chose to sing them for, and the people he chose to sing them with. I learned at a very early age that music and art were full of politics. Enough politics to get you labeled as the enemy of the state. Enough politics to get your passport taken, or to be imprisoned.I was also learning about my parents’ peers, artists whom they loved and adored. Artists like Sonia Sanchez, Amiri Baraka, and Nikki Giovanni, all from the Black Arts Movement. Larry Neal and Amiri Baraka made a statement when they started the Black Arts Repertory Theatre School in Harlem that said essentially that all art should serve a function, and that function should be to liberate Black minds.It is from that movement that hip-hop was born. I was lucky enough to witness the birth of hip-hop. At first, it was playful, it was fun, but by the mid to late 1980s, it began finding its voice with groups like Public Enemy, KRS-One, Queen Latifa, Rakim, and the Jungle Brothers. These are groups that started using and expressing Black Liberation politics in the music, which uplifted it, made it sound better, and made it hit harder. The first gangster rap was that… when it was gangster, when it was directly challenging the country it was being born in.As a teenager, I identified as a rapper and an actor. I would argue with school kids who insisted, “It’s not even music. They’re just talking.” I would have to defend hip-hop as music, sometimes even to my parents, who found the language crass. But when I played artists like KRS-One and Public Enemy for my parents, they said, “Oh, I see what they’re doing here.”When Public Enemy rapped, “Elvis was a hero to most, But he never meant shit to me you see, Straight up racist that sucker was, Simple and plain, Motherfuck him and John Wayne, ‘Cause I’m Black and I’m proud, I’m ready and hyped plus I’m amped, Most of my heroes don’t appear on no stamps,” my parents were like Amen. They understood. They understood why I needed to blast that music in my room 24/7. They understood.When the music spoke to me in that way, suddenly I could pull off moves on the dance floor like doing a flip that I couldn’t do before. That’s the power of music. That’s power embedded in music. That’s why Fela Kuti said that music is the weapon of the future. And, of course, there’s Nina Simone and Billie Holiday. What’s Billie Holiday’s most memorable song? “Strange Fruit.” That voice connected, was speaking directly to the times she was living in. It transcended the times, where to this day, when you hear this song and you understand that the “strange fruit” hanging from Southern trees are Black people who have been lynched, you understand how the power of the voice, when you connect it to something that is charged with the reality of the times, takes on a greater shape.Collis Browne: Public Enemy broke open so much. I grew up in Toronto, in a mostly white community, but I was into some of the bigger American hip-hop acts who were coming out. Public Enemy rose to a new level. Before them, we were only connecting with punk and hardcore music as the music of rebellion.Saul Williams: Public Enemy laid down the groundwork for what hip-hop is: “the voice of the voiceless.” It was only after Public Enemy that you saw the emergence of huge groups in France, Germany, Bulgaria, Egypt, and across the world. There were big acts before them. Run DMC, for instance, but when Public Enemy came out, marginalized groups heard their music and said, “That’s for us. Yes, that’s for us.” It was immediately understood as music of resistance.Collis Browne: What have you seen or listened to out in the world that has a clear political goal, but has been appropriated and watered down?Saul Williams: We can stay on Public Enemy for that. Under Secretary Blinken, Chuck D became a US Global Music Ambassador during the genocide in Gaza. There are photos of him standing beside Secretary Blinken, accepting that role, while understanding that the US has always used music as a cultural propaganda tool to express soft power. I remember learning about how the US uses this “soft power” when I was working in the mid-2000s with a Swiss composer, who has now passed, named Thomas Kessler. He wrote a symphony based on one of my books, Said the Shotgun to the Head, and we were performing it with the Cologne, Germany symphony orchestra, when I heard from the head of the orchestra that, in fact, their main financier was the US Government through the CIA.During the Cold War, it was crucial for the American Government to put money into the arts throughout Western Europe to try to express this idea of “freedom,” as opposed to what was happening in the Eastern (Communist) Bloc. So it was a long time between when the US Government started enlisting musicians and other artists in their propaganda campaigns and when I encountered this information.There’s a documentary called Soundtrack to a Coup d’État, which talks about how the US Government used (uses) music and musicians to co-opt movements and propagate the idea of American freedom and democracy outside the US in the hope of winning over the citizens of other countries without them even realizing that so much of that art is there to question the system itself, not to celebrate it. Unfortunately, there are situations in which an artist’s work is co-opted to be used as propaganda, and the artist buys into it. They become indoctrinated, and you realize that we’re all susceptible to the possibility of taking that bait."

}

,

"relatedposts": [

{

"title" : "A Call to Arms",

"author" : "Jeremiah Zaeske",

"category" : "essays",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/a-call-to-arms",

"date" : "2026-02-03 11:17:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/1000013371.jpeg",

"excerpt" : "Birds perch on the gaps in barbed wire",

"content" : "Birds perch on the gaps in barbed wireBeckoning us to join themWater trickles through the obstruction in its path as if it were nonexistentWe have forgotten that we are waterVines weave a tapestry through metalIf trees cannot find a gap in the fence they will squeeze their way through,engulf it,absorb the border within themselvesThis is a call to armsLOVEI want my love to break through glassI want it to uproot the weeds that have grown in my heart as it picks through yoursI want it to burn through every piece of fabric stained with bloodLove was never a pacifistWhere there is evil there will also be two kinds of joyOne that revels in the misery,grinning faces posing with dead bodieswhile others look on in silence growing numbBut love is the joy of resilienceThe joy of knowing we will always need eachother enoughto tear down the walls and reach out our handsin spite of everything, even deathTo grab at the roots of ourselvesand plant flowers in place of the hate that’s been sown,though the stems may have thornsThis love will be the callouses born from fighting our waythrough rough brick and sharp glass edges,but they’ll just make it that much softer when palm meets palmThis love will be the fertilizer for a garden of scar tissue,never again to be buried under earth and thick skinThis love will be the seeds taking rootafter a long cold winter,sprouting from our chests and cracks in the pavementto greet a long-awaited springA NURTURING DEATHShot-gun weddingDrive-by baby showerClose-range baptismBurn down the forest,the church and the steepleThe baby’s gender is Destruction,Death, andPrimordial ChaosWe are unlocking the worlds they shut away,beyond the talons of textbook definitions,worlds they swore could never existworlds they swore to destroyWe’re pulling out fragmentsthrough the cracked open doorto fill the potholes and cracked cementof our bodymindsouls,to make salve for the woundsThe ones they claimed were pre-existingand unfillableand unfixableand “who’s going to pay for that?”We are toppling immovable fortresseslimb by limb,peeling off skin and tearing through tendonto reveal the brittle forgeries of boneWe are de-manufacturing wildernessNot just free reign for the treesor even all the life they hold,but regrowth for the village of Ahwahnee,birds pecking out the eyes of campers at YosemiteWhat remains will be fed back into the ecosystem,into the bellies of bears and mountain lions,swallowed by insects and earthuntil it’s decayed enough to fertilize the soiland grow foodmedicinelifeA rebirthA nurturing death"

}

,

{

"title" : "This is America: Land of the Occupied, Home of the Capitalists",

"author" : "Mattea Mun",

"category" : "essays",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/this-is-america",

"date" : "2026-02-03 11:11:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/ice-protest-2-gty-gmh-260130_1769810312461_hpMain.jpg",

"excerpt" : "They tell us we live in the land of the free. They declare, “we the people,” and we assume they mean us when we were only ever defined – designed – to be the fodder to build their “life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness.”",

"content" : "They tell us we live in the land of the free. They declare, “we the people,” and we assume they mean us when we were only ever defined – designed – to be the fodder to build their “life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness.”On a Thursday, a 2-year-old girl returned home from the store with her father, Elvis Tipan-Echeverria, when unknown, masked agents trespassed onto their driveway and smashed the window in. In the name of defending the pursuit of happiness, she, with her father, was shoved into a car with no car seat and placed on a plane to Texas. This little girl was eventually returned to her mother in Minnesota; her father – still imprisoned in the land of the free.In the name of liberty, 5-year-old Liam Ramos, with his father, was seized and flown away from his mother and his home to sit in a detention facility in Texas, where his education will halt, his freedom is non-existent, and his pursuit of happiness – denied.In the name of life, Chaofeng Ge was “found” hanging, dead, in a shower stall in detention, his death declared a suicide though his hands and feet were bound behind his back, a fact evidently not deemed worthy of being initially disclosed. Geraldo Lunas Campos was handcuffed, tackled and choked – murdered – in detention, in an effort to “save” him. Victor Manuel Diaz, too, was “found” dead, a “presumed suicide,” the autopsy – classified.American voters like to declare that our present reality isn’t “what they voted for,” despite the fact that one of Donald Trump’s campaign promises in the 2024 election was to “carry out the largest domestic deportation operation in American history,” inevitably according to xenophobic and white supremacist lines. What many of us fail to remember is that this is not the first time we have voted for this. Indeed, I am not confident there is any point in American history that we have not collectively voted for this, regardless of so-called “party lines.”We Have Been Here BeforeWhile the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) was founded in 2003, slavery and genocide predated the very Constitution of the United States, the bodies of African Americans and Indigenous Americans brutalized and broken in the service of laying the foundations of (white) American wealth. Though slavery was “abolished” in 1865 by the 13th amendment, this did not end the policing of racialized bodies.During the Reconstruction era, convict leasing and black codes preserved the conditions and social hierarchy that existed under slavery. Moreover, any legal rights afforded Black Americans were and still are persistently undermined by their inferior social caste, whereby their deaths and suffering at the hands of law enforcement, the healthcare system and other Americans often goes unprosecuted and/or unpunished.Within WWII-era Japanese internment camps, inmates were stripped of their freedom to move, subjected to harsh living conditions and coerced to partake in underpaid, unprotected labor.The Lucrative Business of Slavery and its Bipartisan ProfiteersTo this day, the prison system remains a potent vestige of slavery, again for the sake of profit, as inmates’ human rights are systematically liquidated. As early as the 1980s, the federal government has contracted for-profit prison corporations to operate federal detention facilities. Today, over 90% of ICE detention facilities are operated by for-profit prison corporations as of 2023, a figure which increased from 79% within Biden’s presidency alone.These trends, in conjunction with the ongoing mass detainments of America’s people of color, are not surprising when we consider the immense profits our politicians and some Americans stand to gain, made possible by the continuous enslavement of racialized bodies.Our bodies are their profit.Under the Voluntary Work Program, forced carceral labor is codified, whereby detainees are to receive “monetary compensation of not less than $1.00 per day of work completed,” their “voluntary” labor absolving them of legal employee protections, such as minimum wage. And although ICE affirms that “all detention facilities shall comply with all applicable health and safety regulations and standards,” there is confusion as to how these standards are checked, especially when we consider the Trump administration closed the DHS’s Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties in March 2025.Nevertheless, several lawsuits and detainee testimonies attest to the fact that the work program is rarely voluntary, the survival of themselves and the facilities imprisoning them hinging upon their labor and minimal income. Indeed, many detainees are expected to purchase their own basic products, such as toilet paper and soap. Other detainees recall being threatened with solitary confinement, poorer living conditions and material punishment if they refused to work. Martha Gonzalez was denied access to sanitary pads when she requested a day off work, demonstrative of a larger pattern of ICE’s refusal to provide hygiene products and spaces to maintain one’s hygiene in a dignified manner.In 2023, GEO Group, one of the largest for-profit prison corporations, made over $2.4 billion in revenue, of which ICE, as their largest customer, accounted for 43%, or $1.04 million. ICE also accounted for 30% of CoreCivic’s – another large for-profit prison corporation – revenue. Thus, our bodies enable these companies to amass hundreds of millions in profit.Incidentally, CoreCivic and GEO Group are among the private prison companies that contribute the most to political campaigns, parties and candidates. In the 2024 election cycle, GEO Group gave $3.7 million in contributions, including $1 million to Make America Great Again Inc, while CoreCivic provided roughly $785,000 in contributions. While Republican candidates and committees have been the recipient of the large majority of these funds in recent years, Democrats and the Democratic Party are also guilty of accepting funding from these corporations, among others. In the 2024 cycle, CoreCivic contributed $50,000 to the Democratic Lieutenant Governors Association and Kamala Harris received $9,500 from GEO Group.The opportunities for profit extend even further beyond the U.S.’s borders as more and more nations are gradually entering deals to imprison noncitizen deportees coming from the U.S. In November, $7.5 million was paid out to Equatorial Guinea for this purpose. Alongside other Latin American countries like Costa Rica and El Salvador, Argentina is also rumored to strike their own deal with the U.S.Our bodies are their profit.The ongoing ICE campaign stands as a bipartisan issue, mirroring the ways our country’s deepest social inequalities have been repeatedly upheld on all sides of the political aisle throughout our history.The Occupied Mind and BodyMoreover, the policing of racialized bodies does not merely pertain to the body alone as a site to be moved and removed. Rather, this violence is also waged in our social spaces, in our fears and inside of our bodies.In the classroom, our curriculums hardly, if at all, represent a version of events where we existed and meanwhile the current administration actively tries to erase any part of history we are given a claim to. Such initiatives, too, have been supported for generations, reflected in the 150-year period Indigenous American and Hawaiian children were forcibly taken from their homes and sent to boarding schools designed to facilitate their assimilation and more seamless theft of their native lands.In our social spaces and lives – if not yet brutally taken – liberty and the pursuit of happiness is not ours for the taking. We are perpetually told under what conditions our movement is permissible. Decades of redlining have, in many ways, preserved segregation and pooled the best resources for the white and the wealthy to the detriment of communities of color.But even this is not enough.They police us from the inside, too. In exchange for gifts like food and photographs of her daughter, a Nicaraguan woman was subjected to have sex with a now former ICE officer whilst in detention. A “romantic relationship,” according to federal prosecutors. Our suffering is still romanticized even when guilt has been assigned. What they still do not realize is that there is no place for romance to reside so long as we remain shackled, our bodies – looted.From the inside, they forcibly remove our reproductive organs, then and now. Many of us were among the 70,000 forcibly sterilized in the 20th-century, deemed “unfit” to reproduce. As we speak, 32% of surgeries performed in ICE detention facilities are performed without proper authorization, and there are reports of mass hysterectomies being exacted behind closed doors.They dictate our movements, lock us up, take our insides out, inject their fantasies onto and into our bodies, deprive us of our right to learn and to work and to live. And even if they have not yet come bounding at our doorstep, we lie anxiously in wait for the moment our past may catch up with us and seep, once again, back into our present.And yet, they have the audacity to say that it is by our hands that we are dying; that if only we had lived and loved differently, things wouldn’t be this way. In the name of safety and peace, they force our bodies into hiding or otherwise out onto the streets, despite the fact that only 5% of us have been implicated in a violent crime. In the name of safety, they drag a half-naked ChongLy Thao into snow-covered streets for existing, in their eyes, incorrectly; that is, non-whitely. In the name of safety, a one-year-old and her father are pepper-sprayed in the eyes whilst sitting in their car at the wrong time.Dismantling the Oppressor to Dismantle OppressionFor all the state’s claims that a “war on crime” is being waged, it has always been and remains a war against our bodies, the means with which they wish to realize ICE’s utopic “Amazon Prime for human beings.” Similarly, the War on Drugs only ever served to terrorize our communities, to lock up and exploit our bodies. Meanwhile, this matter of “crime” never dissipated. For centuries, they tell us that it is our fault – our heinous “crimes” – that we are stripped of our families and our dignity. Meanwhile, politicians of all parties and colors have sat idle even while claiming to bear our interests to heart. We forget that they hold their money closer.And, not so unlike the slave catchers recruited and paid out to return runaway slaves to their owners, so, too, it is we who are being recruited and paid out to bind and beat one another, to tease out the “other.” That is, unless we bring ourselves to see ourselves not only in the “other,” but in the ones dragging our tired feet across the pavement, forcing our bodies into further submission, pulling the trigger – all whilst looking us dead in the eye.It was James Baldwin who said, “Everyone you’re looking at is also you. You could be that person. You could be that monster, you could be that cop. And you have to decide, in yourself, not to be.”Whilst the money and military might of the state and the oppressive systems that prop it up are, no doubt, daunting, their power is nevertheless maintained by individual choices made in the service of oppression and possession, as opposed to liberation. However, it is also important to remember that other individual choices are the reason we remain today, more free than before even if that freedom may be incomplete. Thus, just as individual choices have the power to oppress, so, too, individual choices have the power to resist oppression; to hold our people in check; to liberate.Only through our decision to not become the monster we fear do we have any hope of collective liberation."

}

,

{

"title" : "Couture in Paris, Cuts at the 'Post'",

"author" : "Louis Pisano",

"category" : "essay",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/bezos-sanchez-paris-couture-week-wapo-layoffs",

"date" : "2026-02-02 10:49:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/Cover_EIP_Bezos_Sanchez_Pisano.jpg",

"excerpt" : "The Cruel Irony of the Bezos-Sánchez Empire",

"content" : "The Cruel Irony of the Bezos-Sánchez EmpireLate on January 25, as snow dusted Washington, about 60 foreign correspondents at The Washington Post hit send on an email that felt like a last stand. They had dodged gunfire in Ukraine, documented Iran’s water crises and protester crackdowns, risked sources’ lives in gang territories. Now they faced their own existential threat: rumors of up to 300 company-wide layoffs, with foreign desks, sports, metro, and arts likely gutted. Their collective letter to owner Jeff Bezos was direct, almost pleading.“Robust, powerful foreign coverage is essential to The Washington Post’s brand and its future success in whatever form the paper takes moving forward,” they wrote. “We urge you to consider how the proposed layoffs will certainly lead us first to irrelevance, not the shared success that remains attainable.” They offered flexibility on costs but drew a line: slashing overseas reporting in Trump’s second term, amid global flashpoints, would hollow out the institution they had built.Whether Bezos opened that email remains unclear. As of this writing, he has not publicly responded to it. In fact, Bezos was 4,000 miles away, strolling hand-in-hand with Lauren Sánchez Bezos into Schiaparelli’s Haute Couture show in Paris. Flashbulbs popped as they arrived, Sánchez in a blood red skirt suit from the house and a white crocodile bag. Hours on, she switched to a steel-blue-gray vintage Dior pencil-skirt suit, its enormous fur collar evoking a mob wife, for Jonathan Anderson’s couture debut with the house.The two didn’t just sit front row, either. Backstage at Dior, Bezos and Sánchez posed with Anderson and LVMH CEO Delphine Arnault. Sánchez lunched with Anna Wintour at The Ritz and was allegedly dressed by Law Roach, the “image architect” behind Zendaya’s accession to fashion darling, who once declared fashion’s power to challenge norms and amplify the marginalized. Roach reshared Sánchez’s Instagram stories, crediting the vintage Dior; later, they toured Schiaparelli’s atelier together. The partnership felt sudden and loaded.Back in D.C., the newsroom simmered. Staffers posted on X under #SaveThePost, Yeganeh Torbati recounting government violence against protesters, Loveday Morris describing blasts rattling windows and the mortal risks to sources, tagging Bezos directly in urgent appeals. In a guild-prompted twist meant to amplify the message, the Washington-Baltimore News Guild encouraged tagging even Lauren Sánchez, though not every reporter followed through. The betrayal stung deeper after years of buyouts, a libertarian-tilted Opinions section, a rebranded mission (“Riveting Storytelling for All of America”) that rang corporate. Losses topped $100 million in 2024 and now the axe is hovering over desks that produced the scoops Bezos once praised when he bought the paper for $250 million in 2013. Now, Bezos parties on in Paris, his wife climbing fashion’s ranks.While the billionaires party, a profound unease is permeating the American media landscape, exacerbated by political shifts and technological disruptions that empower owners like Bezos to sideline core missions in favor of personal ventures. The press, once a vigilant watchdog against authority, now frequently finds itself complicit with power structures, buckling under misinformation, partisan censorship, and budgetary constraints that stifle investigative depth. This dynamic deprives the public of the unflinching journalism that is capable of exposing foreign policy overreaches or everyday human struggle, amplified by economic slowdowns and subscription fatigue in an increasingly fragmented ecosystem. With eroding confidence driving audiences to social platforms, now eclipsing traditional TV and websites as the primary news source in the U.S., the fallout further deepens this public distrust.To be clear, fashion isn’t innocent in this. It loves to posture as progressive, touting body positivity, diversity, resistance as it’s relevant, but rolling out the red carpet for the ultra-rich when the checks clear, especially when the checks come from people whose fortunes are built on real harm. Once upon a time, you couldn’t simply buy your way into the Met Gala; invitations were curated by Wintour based on cultural relevance, creative influence, and a carefully guarded sense of who truly belonged in the room. That’s all over now. The Bezoses have turned every norm in fashion on its head, sponsoring the 2026 Met Gala (funding the event and reportedly influencing invites), making their debut as a couple in 2024, and now leveraging those ties to claim space in couture’s inner circles. Bezos and Sánchez’s couture jaunt is just the latest proof that fashion’s gates, once guarded by creativity and taste, now swing widest for raw wealth and access.Wintour lunches and their prominent sponsorship role in the Met Gala don’t help quell the whispers that Bezos is eyeing Condé Nast (Vogue, Vanity Fair, The New Yorker) as a “wedding gift” to Sánchez. Rumors denied yet persistent, revived by every Paris sighting.Not everyone in fashion is staying silent. Some insiders are pushing back hard against the normalization. Gabriella Karefa-Johnson, a longtime voice in the industry, posted bluntly on X: “The hyper normalization is doing my head in… keep your mouth shut about ICE if you’re mingling with them, seating them, dressing them. Accepting their cash.” She called out Amazon’s cloud systems as the backbone of DHS deportation operations and billions in government contracts that sustain what she called “Trump’s terror machine,” concluding that Bezos and Sánchez are at couture simply because they are rich—and their wealth comes from profoundly harming millions daily. “I feel crazy,” she wrote. While couture has always been a bastian of the uber-rich, Karefa-Johnson’s frustration underscores how even fashion’s own are starting to question the cost of that welcome.If that Conde-Nast deal ever materializes, the consequences would compound because control over fashion’s most influential titles would allow Bezos the opportunity to shape narratives around billionaires, soften coverage of labor abuses, environmental costs, or surveillance contracts. The same hand that funds AWS’s CIA contracts, DoD cloud deals, ICE enforcement tools, fossil-fuel operations, warehouse injuries, anti-union tactics, and small-business-crushing monopoly would quietly steer the stories about wealth and style. Already deferential to its biggest advertisers and attendees, fashion journalism would fold into the same closed loop, fusing tech dominance with cultural gatekeeping into one unassailable private empire—all of it ultimately bankrolling the yachts, the space joyrides with Katy Perry, the private-jet hops to couture shows and fashion influence, to polish an image that the Post’s own reporters once might have skewered.[x] It’s almost elegant the way one empire’s dirt gets laundered through another.It’s cruelly ironic how wide the gap between the risks assumed by WaPo correspondents tasked with holding power to account and the comfort with which their owner moves among the powerful in Paris actually is. Fashion has political power, as Roach once said. It can challenge and provoke. It can also resist. But when it courts figures like Bezos, whose empire thrives on the very inequalities it sometimes pretends to critique, it becomes another asset in his already enormous portfolio.But there is no challenge, no provocation. There is no major resistance. Instead, there’s champagne and constant disassociation. Somewhere between the clink of glasses and the photos, Bezos and his wife get a glow up while The Washington Post newsroom waits, knowing the cuts are coming but not yet here. No one is confused about what happened; this is simply how the trade now unfortunately works.Wealth drifts through media, fashion, culture, picking up prestige and shedding people along the way. Whether Bezos ever read the letter is beside the point. The stranger thing is how little anyone expects him, or anyone like him, to answer anymore."

}

]

}