Digital & Print Membership

Yearly + Receive 8 free printed back issues

$420 Annually

Monthly + Receive 3 free printed back issues

$40 Monthly

Special Feature:

Reclaiming Feminism and Collective Liberation

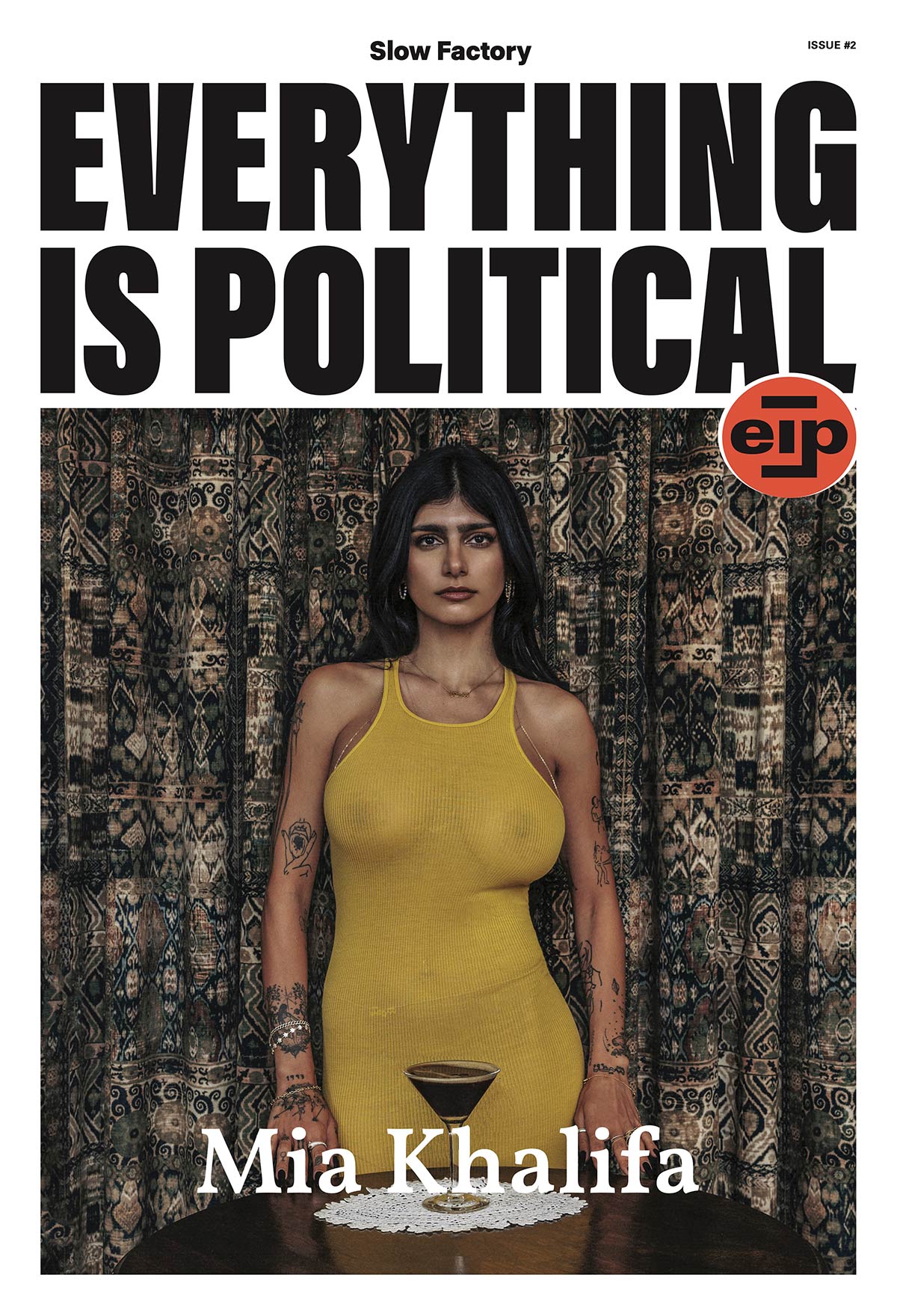

Mia Khalifa & Céline Semaan on Healing, Identity, and Political Awakening

Reclaiming Feminism and Collective Liberation

CÉLINE SEMAAN: I have so many questions—they are a bit intense. So we are going to start with the intensity immediately… Anjed we woke up and the news was so disgusting. I mean this is our reality.

We joke and laugh because we’ve developed this amazing sense of humor, but the world we’ve grown up in has been very very intense. We’ve mastered the art of talking about heavy issues, making it personal because everything is political right?

MIA KHALIFA: Everything.

CÉLINE: I wrote something recently, about how ‘free Palestine’ is also about Lebanon. The Lebanese endured 35 years of war and genocide in Lebanon, all before social media existed. Back then, the media painted us as terrorists, manufacturing consent for the bombings. It’s a humanitarian crisis that’s rarely discussed, though as Lebanese people, it’s been our lived experience.

You and I both grew up in Lebanon. Today, waking up to what’s happening in South Lebanon, Dahiyeh, and Tyre, with 200 people killed just today, is heartbreaking. I hope when this is published, it’s over, but I’m not holding my breath.

As women, especially Arab women, we’ve faced oppression, both from conservative and so-called progressive spaces. How do you reconcile feminism when it doesn’t seem to include us?

MIA: That’s a very good question. Honestly, it’s only in the last few years, as I’ve grown older, that I’ve been able to reconcile those feelings. I realized that you can only control your own views and actions. For a long time, I was immaturely angry at feminism because I felt excluded from it. I felt ostracized, so I responded by rejecting it and, unfortunately, internalizing a lot of misogyny. I didn’t feel supported by that community for much of my life.

I grew up in a predominantly white, predominantly Jewish area in Washington, DC, and Maryland. I didn’t see much support from feminist circles there. It wasn’t until I got older, traveled, and found community with women of color—Indigenous, Latinx, and especially Lebanese and Arab women—that I started to understand. It took time, but I get why others struggle to reconcile their place within feminism. It wasn’t until I got older that I began to find my own.

CÉLINE: Growing up in constant war, having to flee over and over. I’ve moved so many times. Just this morning, I was on a call with my parents, and they’re preparing to flee Lebanon again with everything that’s going on. I’ve lost count of how many times they’ve had to leave and come back. It makes you rethink what home really means.

So now, sitting here in a hotel, I wonder, what does “home” mean to you?

MIA: Home, for me, is hearing your accent and having manoushes around the table. That’s what makes it feel like home—those little reminders that are so important. It’s all that really matters. As long as you’re surrounded by the right people, that’s it.

CÉLINE: This morning, as I was buying manoushe and heading to see you, I felt like, “Wow, I feel at home in New York,” just knowing there’s this place I can go to for that familiar taste. I literally inhaled that manoushe while watching the news, and it hit me—wherever we go, we’re transporting our home with us. It sounds cheesy, but anjad it’s true. We carry it within us—our bodies, our everything. We bring home wherever we are.

MIA: Growing up, the only thing we ever ate at home was Lebanese food, of course. But after moving to America, going out to different restaurants and trying new cuisines became a bit of a tradition. I remember one time we went out for Thai food, and my grandma brought a little Tupperware of tarator to eat with the fried fish.

CÉLINE: No way! That’s so cute!

MIA: At one point, the Thai restaurant actually asked if they could taste it, and then they asked her for the recipe so they could make it themselves—because the fried fish went so perfectly with the tarator.

That’s what home is. You make it wherever you are, even in a foreign restaurant eating a cuisine you’ve never had before. It’s one of my favorite stories about her—she’s an icon!

CÉLINE: That’s so cool! Growing up here, my parents also had a restaurant, and even though it wasn’t a Lebanese restaurant, but my mom made everything Lebanese! It was so fusion. She’d cook American dishes, but with a Lebanese twist. You want a hamburger? We make it kafta burger.

MIA: Sure, but with seven spices! Literally everything had that touch. I put that on everything. Za’atar too.

CÉLINE: What do you put za’atar on?!

MIA: Literally everything! I’ll even put za’atar on my cheese pizza—especially if it’s New York style. It’s so good when it mixes with the grease, like yum! It sounds wild, but honestly, it works!

‘For a long time, I was immaturely angry at feminism because I felt excluded from it. I felt ostracized, so I responded by rejecting it and, unfortunately, internalizing a lot of misogyny. I didn’t feel supported by that community for much of my life.’ — Mia

CÉLINE: Let’s circle back to Everything is Political. Your whole life has been about liberation—liberating our bodies, minds, sexuality, and beauty. What does collective liberation mean to you?

MIA: To me, it’s as simple as the idea that none of us are free until Palestine is free. I don’t see that as a radical statement at all—it perfectly captures the sentiment. It’s a no-brainer for me. I get why you feel the need to defend it, because people probably ask, “What does that mean?” But honestly, if they’re asking, they might not want to get it. It’s always been clear: liberation means everyone. It’s not exclusive, and no one person or group is more entitled to it than another. We all have to work together.

CÉLINE: Even in the U.S., you’ve always advocated for a free Palestine, even before October 7. But since then, with the escalation of violence, the Free Palestine movement has transformed. The world has changed in how America views us and how America sees itself.

From your perspective, what have you observed regarding the sudden embrace of the Free Palestine movement? It used to feel niche and unwelcome, and it’s still not completely accepted— there’s significant censorship and backlash. But it does seem like there are way more people now willing to support the cause, doesn’t it?

MIA: Yeah, exactly. It’s hard to ignore the reality when people who were once neutral or wanted to stay out of it are now realizing just how egregious this situation is. This is pure genocide backed by Western powers, and it’s terrifying. The veil has been lifted, and we’re starting to see the ugly truths of how the world operates—and how it could operate differently if there was the will to change things.

It’s a wake-up call. Watching this unfold for so long, seeing it happen so blatantly, and witnessing the constant stream of heartbreaking videos… It’s heartbreaking that the pain of Arabs has to be exploited like this for people to finally believe it. It’s disgusting and incredibly hurtful.

CÉLINE: You know, sometimes we find ourselves advocating not just for our rights but for our very survival. At the same time, we’re human—we’re evolving, changing, and transforming. I feel a responsibility to ask you about the criticism you’ve received regarding the fetishization of the hijab, for instance. What are your thoughts on that criticism? How do you navigate those conversations, especially given the complexities involved?

MIA: I feel like that criticism is very valid because it comes from a place of young women feeling sexualized for something they didn’t do. I understand that I’m an easy person to target; I’m a public figure, and people can leave comments on my photos and tag me, making it simple to pinpoint the issue onto me.

I have immense compassion for those women and feel a deep guilt that an innocent young woman is being fetishized for something she chooses to embrace as part of her religious beliefs. But I think, as women, we should focus on the larger issue—the patriarchal system that promotes this, produces this and distributes this, which continues to fetishize women. Even if they’re not using Arab actresses, they’re often casting Latin women who could pass as Arab. I’m not the first nor the last to face this; I’m just the one people can identify because there’s a face connected to the name and to the action.

CÉLINE: Absolutely. When we talk about feminism and this idea of purity, it often feels like you have to come from a place of purity to advocate for human rights, right? Do you feel that pressure? It’s almost as if you have to be a saint to be taken seriously in these conversations. What are your thoughts on that?

MIA KHALIFA: Oh my gosh, I completely disagree with that! Most of us don’t come into these mindsets from a place of purity. Many of us are traumatized individuals dealing with so much that we need to work through to reach these realizations. I wasn’t the same person I was even five or six years ago; my thoughts were nowhere near what they are now.

I know it might sound insane, but every single thing I see radicalizes me further and further. The way I thought when I was 20 was influenced by my own internalized misogyny and racism, along with many other issues that shaped my actions and beliefs. But then I started going to therapy and delving deeper into myself, actually growing into my identity. That’s why I feel so secure in who I am now.

CÉLINE: Criticism can be so harsh. Yet in this movement for liberation, there seems to be a punitive mindset, a carceral approach that contradicts the very essence of liberation. The idea that you can publicly punish someone or correct them through harassment is so counterproductive. How do you feel about this? Where do you draw the boundary, and how do you navigate your own evolution and transformation in this public space?

‘The veil has been lifted, and we’re starting to see the ugly truths of how the world operates— and how it could operate differently if there was the will to change things.’ —Mia

MIA: You just have to give people grace. It’s essential to consider intentions before judging actions. At the end of the day, it comes down to listening, understanding, and being empathetic and compassionate when it’s necessary. Of course, not everyone deserves that grace, but for those who do, it can make all the difference.

Ultimately, I believe that to grow and transform in this world, you have to embrace contradictions. You can’t change without acknowledging that you might have to contradict yourself along the way.

CÉLINE: It’s all about grace and generosity. We often discuss radical generosity in our culture. In Arab culture, it’s like this dance where you fight to pay the bill or show up at someone’s house with more than enough. There’s a deep-rooted understanding that sharing and giving are essential parts of our community.

MIA: Oh, exactly! You call ahead and show up at the restaurant six hours early just to slip your credit card to cover the bill. Then you leave and come back, saying, “Oh, I’m so sorry I was late!” It’s all part of that generous spirit.

CÉLINE: Yes, exactly! There’s this radical generosity that you embody so well through your constant acts of giving. I’d love to hear how your approach to giving has evolved and how you’re seeing the impact of your actions. Where do you want to focus your generosity now?

MIA: Thank you for saying that; it really means a lot. I’ve always felt this innate need to contribute because you’re not truly deserving of anything if you’re not also supporting your community. It’s like a mental version of Reaganomics that actually could work if it weren’t so corrupt! That’s how community is supposed to function.

But as I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to realize there’s a big difference between just giving and giving with purpose.

CÉLINE: Your recent tweet really resonated with us: “You get to a point in life when you realize everything is political—the brands you support, the places you patronize, the celebrities you platform, and even the people you date. If they’re not at least trying to be informed, have a stance, and be vocal, then they’re not in alignment.” This was so powerful, especially since we just launched our “Everything is Political” initiative. We knew we wanted to be in conversation with you, and this tweet felt like a perfect alignment!

MIA: Just a couple of years ago, I might have been okay with friends who said things like, “Oh no, I stay out of all that.” But now, if I hear someone say that, I’m genuinely taken aback. Like, what do you mean? It feels almost robotic, like they’re disengaged from reality. We all have a responsibility to each other, regardless of our backgrounds.

Whether you’re walking down the street or staying in a hotel, every action counts. Holding the door open for someone behind you or treating housekeeping staff with respect—these seemingly small gestures reflect our shared humanity. It’s all interconnected, and we need to recognize that our choices impact those around us. Every single role we play comes with responsibility, and it’s time we embrace that fully.

CÉLINE: I feel like that’s very cultural to us, like the idea of responsibility. This is how we were raised—to really understand our place in the world and our responsibility in it. This brings me to addressing “poverty porn”, by showing images of dying brown kids covered in blood.

There’s a gap between that and our dignity as humans. Those images actually hurt our dignity. People say this is one of the most documented genocides, yet it’s not moving the needle because many don’t even see us as human.

So, we started this idea of building a fund for collective liberation so that we can put our money in multiple places at once. It’s not just about feeding the poor or educating the uneducated—categories that are ultimately so colonial. We wanted a fund that was more holistic because it’s a case-by- case situation.

There’s no standardized way to heal the world; it has to be designed in a modular way that fluctuates with the situation. I feel like Arabs understand this inherently, especially Lebanese and people from the Levant. The ways in which we have survived could not have happened if we were stuck in a one- track, standardized mindset. This idea of a fund for collective liberation came to be, and I know it spoke to you. In what ways did it resonate with you?

MIA: That’s exactly the reason. The fact that I don’t just have to commit to education—because education is so important—but if a tragedy strikes, which unfortunately has been happening way too often, I want to be partnered with an organization that can go with the ebb and flow of life. When, thankfully, things are quiet and good, we can fund arts, education, and other things that are important for culture.

CÉLINE: I’m so grateful to be in community with you. I wanted to ask you, oftentimes people ask, “What would you tell your younger self?” But I feel like the question could also be, “What do you think your younger self would say and do now?” Like, what’s your inner child saying to you these days? I feel like there’s a lot of repair we have to do in reconciling with our inner child.

For me personally, my whole healing journey and all of my therapy sessions have focused on my inner child because she’s someone who was born in a war, fled the war, and experienced a lot of neglect. I’m sure that you can relate because you were in Lebanon during that time as well. Our parents were stressed, and we were being neglected.

Now, looking at what’s happening in Gaza, there’s a war on children currently happening, and I feel like our inner children are acting up—they’re being vocal. What does Sarah’s inner child say?

MIA: She says, “Thank you for caring about making sure there’s a place for me to go back to, and thank you for not being ashamed of me anymore. Thank you for doing all the things I would have wanted to do. And can I borrow your shoes?” What does yours say?

CÉLINE: Mine says, “Thank you for being the person who protects me, the person who would have held me and cared for me. Thank you for doing everything you can to ensure that people like us have a place to be, and for never forgetting that you are me.” You know, I’m very much a kid at heart. I mean, I feel like the biggest conversation is about healing, you know? I want to ask you, what’s your practice for healing? How did you invite healing into your life?

MIA: Therapy and mushrooms.

CÉLINE: Oh, wow! yes.

‘Just a couple of years ago, I might have been okay with friends who said things like, “Oh no, I stay out of all that.” But now, if I hear someone say that, I’m genuinely taken aback. Like, what do you mean? It feels almost robotic, like they’re disengaged from reality. We all have a responsibility to each other, regardless of our backgrounds.’

—Mia

MIA: Ya.

CÉLINE: That helped you?

MIA: What caused me to start going to therapy was really just being fed up. I’ve never been against it, so it wasn’t a hard sell.

CÉLINE: Sometimes, culturally, we’re like, “Oh, we’re fine, we’re fine, we’re fine,” you know? And then we don’t take the time.

MIA: I was just in denial. Finally, it got to a point where there was one specific moment where I exploded on a radio host during an interview. The way they introduced me triggered me and felt very disrespectful. It was a sports show, and I just didn’t feel like the way they introduced me was respectful. I exploded on them, and then I got a fine from the SEC because it was live radio, and it went viral. People were like, “This bitch is crazy,” and I was like, “Yeah, this bitch is crazy. She needs to go to therapy, actually.”

So, I went to therapy, and then I realized, oh, that was a trigger because I have unhealed shame from unhealed trauma—from things I did because of my unhealed trauma. So that was the catalyst. Psilocybin and mushrooms has been a lot more recent. When I got access to it in California, it was first in chocolate form, then in gummy form. I started microdosing, and then I worked my way up to proper psilocybin, like just grown mushrooms. I have someone guiding me, or sometimes I follow a schedule. My microdosing is very self-guided. I’ll do a cacao ceremony with a spiritual guide or in a group setting, in a very positive environment. But with microdosing, I just wake up in the morning and decide what flavor I want.

CÉLINE: That’s amazing! I did that for the first time in Montreal when I was in my 20s. Yeah, in my 20s, we would make Nutella sandwiches and put a ton of mushrooms in them, then go out and walk in the forest all day, eating the Nutella sandwiches. It was life-altering for me. I started understanding so much; I did my own little healing, doing that therapy in nature—eating a Nutella sandwich with my friends, walking all day, laughing, and just being in nature.

But then one time, we went inside a little too early, and I realized that if you’re very high on mushrooms and you’re indoors…I got SCARED.

MIA: No, no, I did it at Universal Studios.

CÉLINE: Yeah, it was not okay. No, you cannot be around people. I saw myself in the mirror, and I was like, “No, don’t ever look at yourself in the mirror!”I see why you’re guided now because I did it by myself in my 20s, and now it’s so common, right? There’s a big transformation in the healing space where people are finally recognizing the beauty of it and the power of plant medicine. You did it at Universal Studios?

MIA: I did it at Universal Studios! I cried on the Hogwarts Express, and people had to come and ask my friend, “Is your friend okay?” It was bad. We threw up in the bushes.

In Conversation:

Photography by:

Céline Semaan (author, founder and Slow Factory Creative Director) chats with Mia Khalifa (entrepreneur, digital creator, philanthropist & human rights activist) over manousheh. The two discuss how they navigate being a Lebanese woman in America at this time, Global South generosity, politics, making home in the diaspora and how they reconciled their heritage with their own path to create the type of world they want.

Topics:

Filed under:

Location:

{

"article":

{

"title" : "Reclaiming Feminism and Collective Liberation: Mia Khalifa & Céline Semaan on Healing, Identity, and Political Awakening",

"author" : "Mia Khalifa, Céline Semaan",

"category" : "interviews",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/mia-khalifa-celine-semaan-reclaiming-feminism-collective-liberation",

"date" : "2024-11-01 13:56:00 -0400",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/MIA_IEP_9-thumb.jpg",

"excerpt" : "",

"content" : "CÉLINE SEMAAN: I have so many questions—they are a bit intense. So we are going to start with the intensity immediately… Anjed we woke up and the news was so disgusting. I mean this is our reality.We joke and laugh because we’ve developed this amazing sense of humor, but the world we’ve grown up in has been very very intense. We’ve mastered the art of talking about heavy issues, making it personal because everything is political right?MIA KHALIFA: Everything.CÉLINE: I wrote something recently, about how ‘free Palestine’ is also about Lebanon. The Lebanese endured 35 years of war and genocide in Lebanon, all before social media existed. Back then, the media painted us as terrorists, manufacturing consent for the bombings. It’s a humanitarian crisis that’s rarely discussed, though as Lebanese people, it’s been our lived experience.You and I both grew up in Lebanon. Today, waking up to what’s happening in South Lebanon, Dahiyeh, and Tyre, with 200 people killed just today, is heartbreaking. I hope when this is published, it’s over, but I’m not holding my breath.As women, especially Arab women, we’ve faced oppression, both from conservative and so-called progressive spaces. How do you reconcile feminism when it doesn’t seem to include us?MIA: That’s a very good question. Honestly, it’s only in the last few years, as I’ve grown older, that I’ve been able to reconcile those feelings. I realized that you can only control your own views and actions. For a long time, I was immaturely angry at feminism because I felt excluded from it. I felt ostracized, so I responded by rejecting it and, unfortunately, internalizing a lot of misogyny. I didn’t feel supported by that community for much of my life.I grew up in a predominantly white, predominantly Jewish area in Washington, DC, and Maryland. I didn’t see much support from feminist circles there. It wasn’t until I got older, traveled, and found community with women of color—Indigenous, Latinx, and especially Lebanese and Arab women—that I started to understand. It took time, but I get why others struggle to reconcile their place within feminism. It wasn’t until I got older that I began to find my own.CÉLINE: Growing up in constant war, having to flee over and over. I’ve moved so many times. Just this morning, I was on a call with my parents, and they’re preparing to flee Lebanon again with everything that’s going on. I’ve lost count of how many times they’ve had to leave and come back. It makes you rethink what home really means.So now, sitting here in a hotel, I wonder, what does “home” mean to you?MIA: Home, for me, is hearing your accent and having manoushes around the table. That’s what makes it feel like home—those little reminders that are so important. It’s all that really matters. As long as you’re surrounded by the right people, that’s it.CÉLINE: This morning, as I was buying manoushe and heading to see you, I felt like, “Wow, I feel at home in New York,” just knowing there’s this place I can go to for that familiar taste. I literally inhaled that manoushe while watching the news, and it hit me—wherever we go, we’re transporting our home with us. It sounds cheesy, but anjad it’s true. We carry it within us—our bodies, our everything. We bring home wherever we are.MIA: Growing up, the only thing we ever ate at home was Lebanese food, of course. But after moving to America, going out to different restaurants and trying new cuisines became a bit of a tradition. I remember one time we went out for Thai food, and my grandma brought a little Tupperware of tarator to eat with the fried fish.CÉLINE: No way! That’s so cute!MIA: At one point, the Thai restaurant actually asked if they could taste it, and then they asked her for the recipe so they could make it themselves—because the fried fish went so perfectly with the tarator.That’s what home is. You make it wherever you are, even in a foreign restaurant eating a cuisine you’ve never had before. It’s one of my favorite stories about her—she’s an icon!CÉLINE: That’s so cool! Growing up here, my parents also had a restaurant, and even though it wasn’t a Lebanese restaurant, but my mom made everything Lebanese! It was so fusion. She’d cook American dishes, but with a Lebanese twist. You want a hamburger? We make it kafta burger.MIA: Sure, but with seven spices! Literally everything had that touch. I put that on everything. Za’atar too.CÉLINE: What do you put za’atar on?!MIA: Literally everything! I’ll even put za’atar on my cheese pizza—especially if it’s New York style. It’s so good when it mixes with the grease, like yum! It sounds wild, but honestly, it works!‘For a long time, I was immaturely angry at feminism because I felt excluded from it. I felt ostracized, so I responded by rejecting it and, unfortunately, internalizing a lot of misogyny. I didn’t feel supported by that community for much of my life.’ — MiaCÉLINE: Let’s circle back to Everything is Political. Your whole life has been about liberation—liberating our bodies, minds, sexuality, and beauty. What does collective liberation mean to you?MIA: To me, it’s as simple as the idea that none of us are free until Palestine is free. I don’t see that as a radical statement at all—it perfectly captures the sentiment. It’s a no-brainer for me. I get why you feel the need to defend it, because people probably ask, “What does that mean?” But honestly, if they’re asking, they might not want to get it. It’s always been clear: liberation means everyone. It’s not exclusive, and no one person or group is more entitled to it than another. We all have to work together.CÉLINE: Even in the U.S., you’ve always advocated for a free Palestine, even before October 7. But since then, with the escalation of violence, the Free Palestine movement has transformed. The world has changed in how America views us and how America sees itself.From your perspective, what have you observed regarding the sudden embrace of the Free Palestine movement? It used to feel niche and unwelcome, and it’s still not completely accepted— there’s significant censorship and backlash. But it does seem like there are way more people now willing to support the cause, doesn’t it?MIA: Yeah, exactly. It’s hard to ignore the reality when people who were once neutral or wanted to stay out of it are now realizing just how egregious this situation is. This is pure genocide backed by Western powers, and it’s terrifying. The veil has been lifted, and we’re starting to see the ugly truths of how the world operates—and how it could operate differently if there was the will to change things.It’s a wake-up call. Watching this unfold for so long, seeing it happen so blatantly, and witnessing the constant stream of heartbreaking videos… It’s heartbreaking that the pain of Arabs has to be exploited like this for people to finally believe it. It’s disgusting and incredibly hurtful.CÉLINE: You know, sometimes we find ourselves advocating not just for our rights but for our very survival. At the same time, we’re human—we’re evolving, changing, and transforming. I feel a responsibility to ask you about the criticism you’ve received regarding the fetishization of the hijab, for instance. What are your thoughts on that criticism? How do you navigate those conversations, especially given the complexities involved?MIA: I feel like that criticism is very valid because it comes from a place of young women feeling sexualized for something they didn’t do. I understand that I’m an easy person to target; I’m a public figure, and people can leave comments on my photos and tag me, making it simple to pinpoint the issue onto me.I have immense compassion for those women and feel a deep guilt that an innocent young woman is being fetishized for something she chooses to embrace as part of her religious beliefs. But I think, as women, we should focus on the larger issue—the patriarchal system that promotes this, produces this and distributes this, which continues to fetishize women. Even if they’re not using Arab actresses, they’re often casting Latin women who could pass as Arab. I’m not the first nor the last to face this; I’m just the one people can identify because there’s a face connected to the name and to the action.CÉLINE: Absolutely. When we talk about feminism and this idea of purity, it often feels like you have to come from a place of purity to advocate for human rights, right? Do you feel that pressure? It’s almost as if you have to be a saint to be taken seriously in these conversations. What are your thoughts on that?MIA KHALIFA: Oh my gosh, I completely disagree with that! Most of us don’t come into these mindsets from a place of purity. Many of us are traumatized individuals dealing with so much that we need to work through to reach these realizations. I wasn’t the same person I was even five or six years ago; my thoughts were nowhere near what they are now.I know it might sound insane, but every single thing I see radicalizes me further and further. The way I thought when I was 20 was influenced by my own internalized misogyny and racism, along with many other issues that shaped my actions and beliefs. But then I started going to therapy and delving deeper into myself, actually growing into my identity. That’s why I feel so secure in who I am now.CÉLINE: Criticism can be so harsh. Yet in this movement for liberation, there seems to be a punitive mindset, a carceral approach that contradicts the very essence of liberation. The idea that you can publicly punish someone or correct them through harassment is so counterproductive. How do you feel about this? Where do you draw the boundary, and how do you navigate your own evolution and transformation in this public space?‘The veil has been lifted, and we’re starting to see the ugly truths of how the world operates— and how it could operate differently if there was the will to change things.’ —MiaMIA: You just have to give people grace. It’s essential to consider intentions before judging actions. At the end of the day, it comes down to listening, understanding, and being empathetic and compassionate when it’s necessary. Of course, not everyone deserves that grace, but for those who do, it can make all the difference.Ultimately, I believe that to grow and transform in this world, you have to embrace contradictions. You can’t change without acknowledging that you might have to contradict yourself along the way.CÉLINE: It’s all about grace and generosity. We often discuss radical generosity in our culture. In Arab culture, it’s like this dance where you fight to pay the bill or show up at someone’s house with more than enough. There’s a deep-rooted understanding that sharing and giving are essential parts of our community.MIA: Oh, exactly! You call ahead and show up at the restaurant six hours early just to slip your credit card to cover the bill. Then you leave and come back, saying, “Oh, I’m so sorry I was late!” It’s all part of that generous spirit.CÉLINE: Yes, exactly! There’s this radical generosity that you embody so well through your constant acts of giving. I’d love to hear how your approach to giving has evolved and how you’re seeing the impact of your actions. Where do you want to focus your generosity now?MIA: Thank you for saying that; it really means a lot. I’ve always felt this innate need to contribute because you’re not truly deserving of anything if you’re not also supporting your community. It’s like a mental version of Reaganomics that actually could work if it weren’t so corrupt! That’s how community is supposed to function.But as I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to realize there’s a big difference between just giving and giving with purpose.CÉLINE: Your recent tweet really resonated with us: “You get to a point in life when you realize everything is political—the brands you support, the places you patronize, the celebrities you platform, and even the people you date. If they’re not at least trying to be informed, have a stance, and be vocal, then they’re not in alignment.” This was so powerful, especially since we just launched our “Everything is Political” initiative. We knew we wanted to be in conversation with you, and this tweet felt like a perfect alignment!MIA: Just a couple of years ago, I might have been okay with friends who said things like, “Oh no, I stay out of all that.” But now, if I hear someone say that, I’m genuinely taken aback. Like, what do you mean? It feels almost robotic, like they’re disengaged from reality. We all have a responsibility to each other, regardless of our backgrounds.Whether you’re walking down the street or staying in a hotel, every action counts. Holding the door open for someone behind you or treating housekeeping staff with respect—these seemingly small gestures reflect our shared humanity. It’s all interconnected, and we need to recognize that our choices impact those around us. Every single role we play comes with responsibility, and it’s time we embrace that fully.CÉLINE: I feel like that’s very cultural to us, like the idea of responsibility. This is how we were raised—to really understand our place in the world and our responsibility in it. This brings me to addressing “poverty porn”, by showing images of dying brown kids covered in blood.There’s a gap between that and our dignity as humans. Those images actually hurt our dignity. People say this is one of the most documented genocides, yet it’s not moving the needle because many don’t even see us as human.So, we started this idea of building a fund for collective liberation so that we can put our money in multiple places at once. It’s not just about feeding the poor or educating the uneducated—categories that are ultimately so colonial. We wanted a fund that was more holistic because it’s a case-by- case situation.There’s no standardized way to heal the world; it has to be designed in a modular way that fluctuates with the situation. I feel like Arabs understand this inherently, especially Lebanese and people from the Levant. The ways in which we have survived could not have happened if we were stuck in a one- track, standardized mindset. This idea of a fund for collective liberation came to be, and I know it spoke to you. In what ways did it resonate with you?MIA: That’s exactly the reason. The fact that I don’t just have to commit to education—because education is so important—but if a tragedy strikes, which unfortunately has been happening way too often, I want to be partnered with an organization that can go with the ebb and flow of life. When, thankfully, things are quiet and good, we can fund arts, education, and other things that are important for culture.CÉLINE: I’m so grateful to be in community with you. I wanted to ask you, oftentimes people ask, “What would you tell your younger self?” But I feel like the question could also be, “What do you think your younger self would say and do now?” Like, what’s your inner child saying to you these days? I feel like there’s a lot of repair we have to do in reconciling with our inner child.For me personally, my whole healing journey and all of my therapy sessions have focused on my inner child because she’s someone who was born in a war, fled the war, and experienced a lot of neglect. I’m sure that you can relate because you were in Lebanon during that time as well. Our parents were stressed, and we were being neglected.Now, looking at what’s happening in Gaza, there’s a war on children currently happening, and I feel like our inner children are acting up—they’re being vocal. What does Sarah’s inner child say?MIA: She says, “Thank you for caring about making sure there’s a place for me to go back to, and thank you for not being ashamed of me anymore. Thank you for doing all the things I would have wanted to do. And can I borrow your shoes?” What does yours say?CÉLINE: Mine says, “Thank you for being the person who protects me, the person who would have held me and cared for me. Thank you for doing everything you can to ensure that people like us have a place to be, and for never forgetting that you are me.” You know, I’m very much a kid at heart. I mean, I feel like the biggest conversation is about healing, you know? I want to ask you, what’s your practice for healing? How did you invite healing into your life?MIA: Therapy and mushrooms.CÉLINE: Oh, wow! yes.‘Just a couple of years ago, I might have been okay with friends who said things like, “Oh no, I stay out of all that.” But now, if I hear someone say that, I’m genuinely taken aback. Like, what do you mean? It feels almost robotic, like they’re disengaged from reality. We all have a responsibility to each other, regardless of our backgrounds.’—MiaMIA: Ya.CÉLINE: That helped you?MIA: What caused me to start going to therapy was really just being fed up. I’ve never been against it, so it wasn’t a hard sell.CÉLINE: Sometimes, culturally, we’re like, “Oh, we’re fine, we’re fine, we’re fine,” you know? And then we don’t take the time.MIA: I was just in denial. Finally, it got to a point where there was one specific moment where I exploded on a radio host during an interview. The way they introduced me triggered me and felt very disrespectful. It was a sports show, and I just didn’t feel like the way they introduced me was respectful. I exploded on them, and then I got a fine from the SEC because it was live radio, and it went viral. People were like, “This bitch is crazy,” and I was like, “Yeah, this bitch is crazy. She needs to go to therapy, actually.”So, I went to therapy, and then I realized, oh, that was a trigger because I have unhealed shame from unhealed trauma—from things I did because of my unhealed trauma. So that was the catalyst. Psilocybin and mushrooms has been a lot more recent. When I got access to it in California, it was first in chocolate form, then in gummy form. I started microdosing, and then I worked my way up to proper psilocybin, like just grown mushrooms. I have someone guiding me, or sometimes I follow a schedule. My microdosing is very self-guided. I’ll do a cacao ceremony with a spiritual guide or in a group setting, in a very positive environment. But with microdosing, I just wake up in the morning and decide what flavor I want.CÉLINE: That’s amazing! I did that for the first time in Montreal when I was in my 20s. Yeah, in my 20s, we would make Nutella sandwiches and put a ton of mushrooms in them, then go out and walk in the forest all day, eating the Nutella sandwiches. It was life-altering for me. I started understanding so much; I did my own little healing, doing that therapy in nature—eating a Nutella sandwich with my friends, walking all day, laughing, and just being in nature.But then one time, we went inside a little too early, and I realized that if you’re very high on mushrooms and you’re indoors…I got SCARED.MIA: No, no, I did it at Universal Studios.CÉLINE: Yeah, it was not okay. No, you cannot be around people. I saw myself in the mirror, and I was like, “No, don’t ever look at yourself in the mirror!”I see why you’re guided now because I did it by myself in my 20s, and now it’s so common, right? There’s a big transformation in the healing space where people are finally recognizing the beauty of it and the power of plant medicine. You did it at Universal Studios?MIA: I did it at Universal Studios! I cried on the Hogwarts Express, and people had to come and ask my friend, “Is your friend okay?” It was bad. We threw up in the bushes."

}

,

"relatedposts": [

{

"title" : "Nature As the Battlefield: Ecocide in Lebanon and Corporate Empire",

"author" : "Sarah Sinno",

"category" : "essays",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/ecocide-lebanon-chemical-warfare",

"date" : "2026-02-25 15:16:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/PHOTO-2026-02-25-13-34-24%202.jpg",

"excerpt" : "",

"content" : "Photo Credit: Sarah SinnoOn February 2, the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL)issued a statement announcing that Israeli occupation forces had instructed their personnel to remain under cover near the border between south Lebanon and occupied Palestine. They were ordered to keep their distance because the IOF had planned aerial activity involving the release of a “non-toxic substance.” Samples collected and analyzed by Lebanon’s Ministries of Agriculture and Environment, in coordination with the Lebanese Army and UNIFIL, confirmed that the substance sprayed by Israel was the herbicide, glyphosate. Laboratory results showed that, in some locations, concentration levels were 20 to 30 times higher than normal. Not to mention, this is not the first instance of herbicide spraying over southern Lebanon, nor is the practice confined to Lebanon. Similar tactics have been documented in Gaza, the West Bank, and Quneitra in Syria.While the IOF didn’t provide further explanation as to its purpose, these operations are part of a broader Israeli strategy to establish so-called “buffer zones” by dismantling the ecological foundations upon which communities depend. The deployment of chemical agents kills vegetation, producing de facto “security” no-go areas that empty entire regions of their Indigenous inhabitants. Cultivated fields are deliberately destroyed, soil fertility declines, and water systems become polluted. Farmers lose their livelihoods, and communities are forcibly uprooted. Demographic realities are reshaped, and space is incrementally cleared for future settlers. Simply put, these tactics function as a mechanism of displacement, dispossession, and elimination—and are importantly part of a long history of this kind of colonial territorial engineering.Glyphosate and Ecological HarmFor decades, glyphosate has been marketed as a formulation designed to kill weeds only and increase crop yields. But the consequences of its use on humans and the environment cannot be ignored: In 2015, Glyphosate was classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as “probably carcinogenic to humans,” and it has been associated with a range of additional health risks, including endocrine disruption, potential harm to reproductive health, as well as liver and kidney damage. In November of last year, the scientific journal Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology formally withdrew a study published in 2000 that had asserted the chemical’s safety.Beyond its human health implications, glyphosate is ecologically harmful. Studies have shown that it degrades soil microorganisms; others have linked it to increased plant vulnerability to disease. It can also leach into water systems, contaminating surface and groundwater sources. Exposure may be lethal to certain species like bees. Even when it does not cause immediate mortality, glyphosate eliminates vegetation that provides habitat and shelter for bees, birds, and other animals, disrupting food webs and ecological balance. What’s more, research indicates that glyphosate can alter animal behavior, affecting foraging and feeding patterns, anti-predator responses, reproduction, learning and memory, and social interactions.Despite a growing body of scientific literature highlighting its risks to both human health and the environment, and bearing in mind that corporate giants manufacturing such products have been known to fund and even ghostwrite research to promote the opposite, glyphosate remains the most widely used herbicide globally.The Monsanto ModelTo understand how it became so deeply entrenched, normalized within agriculture systems in some contexts, and used as a weapon of war in others, it is necessary to look more closely at the corporation responsible for its global expansion: Monsanto.Founded in 1901, Monsanto’s corporate history reflects a longstanding pattern of chemical production linked to environmental devastation. Over the past century, the corporation has manufactured products later proven harmful and has faced tens of thousands of lawsuits, resulting in billions of dollars in settlements.Among the products it manufactured were polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), synthetic industrial chemicals that were eventually banned worldwide due to their toxicity. Through their production and disposal, including the discharge of millions of pounds of PCBs into waterways and landfills, Monsanto contributed to some of the most enduring chemical contamination crises in modern history, the consequences of which continue to reverberate today.One of the most notorious cases unfolded in Anniston, Ala., where Monsanto’s chemical factory polluted the entire town from 1935 through the 1970s, causing widespread harm to the community. Despite being fully aware of the toxic effects of PCBs, the company concealed evidence, according to internal documents, a conduct that reflects a longstanding pattern of disregard for both environmental care and human health. Whether in the case of PCBs or glyphosate, the underlying logic remains consistent: ecological systems and communities are harmed in order to prioritize profit and, at times, territorial expansion.Monsanto also became the world’s largest seed company. Through the enforcement of restrictive patents on genetically modified seeds, the corporation consolidated unprecedented control over global food systems. By prohibiting seed saving, a practice upheld by farmers and Indigenous communities for millennia, it undermined seed sovereignty and compelled farmers to purchase new seeds each season rather than replanting from their own harvests. What had long functioned as part of the commons since the origins of human civilization, the foundational basis of food and life itself, was privatized. Monsanto transferred control over seeds from cultivators to corporations, further creating systems of structural dependency.What was once embedded in reciprocal relationships between land, seed, and cultivator is now controlled by the same chemical-producing corporations implicated in the degradation of land—as is the case of what is unfolding in southern Lebanon. Power is thus consolidated within an industrial architecture that, at times, prohibits the exchange and regeneration of seeds and, at other times, renders the land uninhabitable. In both cases, it undermines the ability to grow food and remain rooted in the land, thereby threatening the conditions necessary for survival.Chemical WarfareAlongside its record of manufacturing carcinogenic products, dumping hazardous chemicals into the environment, and contributing to the destruction of agricultural systems, Monsanto has also been linked to chemical warfare. During the Vietnam War (1962–1971), it was among the U.S. military contractors that manufactured Agent Orange, a defoliant used to strip forests and destroy crops that provided cover and food to Vietnamese communities.The chemical contained dioxin, one of the most toxic compounds known, contributing to the defoliation of millions of acres of forest and farmland. It has been associated with hundreds of thousands of deaths and long-term illnesses, including cancers and birth defects.Although acts of ecocide long predated this period, well before the term itself was coined, it was in the aftermath of Agent Orange that the word “ecocide” was first used to describe the deliberate destruction of ecosystems and began to enter political and legal discourse.The Vietnam War exposed a structural link between chemical production, corporate power, and a military doctrine in which ecosystems and farmlands are targeted precisely because they sustain human life. Nature, because it nourished, protected, and anchored Indigenous communities, was treated as an obstacle to military and imperial control. As a result, it became a battlefield in its own right.Capital and RuinThis historical precedent continues to reverberate today in Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria. Decades apart, these are not isolated acts of ecological destruction but part of a continuous trajectory carried out by the same imperial, corporate, and financial machinery.In 2018, Monsanto was acquired by Bayer. Bayer’s largest institutional shareholders include BlackRock and Vanguard, the world’s two largest asset management firms.Both firms have been identified in reports, including those by UN Special Rapporteur Francesca Albanese, as major investors in corporations linked to Israel’s occupation apparatus, military industry, and surveillance infrastructure. These include Palantir Technologies, Lockheed Martin, Caterpillar Inc., Microsoft, Amazon, and Elbit Systems.Mapping these financial linkages reveals how ecocide is structurally embedded within broader systems of violence that are deeply entrenched and mutually reinforcing. Ecocide and genocide are financed through overlapping capital networks that connect chemical production, militarization, and territorial control.The spraying of glyphosate over agricultural land in southern Lebanon must therefore be situated within this historical continuum. The same corporate-financial structure that profits from destructive chemicals and agricultural control is interwoven with the industries that maintain a settler-colonial stronghold."

}

,

{

"title" : "Nothing Is ”Apolitical”: Why I Refused to Exhibit at the Venice Biennale",

"author" : "Céline Semaan",

"category" : "",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/nothing-is-apolitical",

"date" : "2026-02-24 15:51:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/Cover_EIP_Apolitical_Venice_Biennale-19ed6f.jpg",

"excerpt" : "After October 2023, the art world felt comfortable discriminating against Arab artists and dehumanizing us when Israel began carpet bombing Gaza leading to a genocide . For a few years since that moment, many Arab artists saw their work rejected, refused, or cancelled from shows, publications, and galleries. But in 2025, the propaganda against Arabs began to be debunked and the world recognized that Israel was in fact a colonial military occupation decimating Indigenous people, and curiously, we started receiving invitations to participate in the art world again.",

"content" : "After October 2023, the art world felt comfortable discriminating against Arab artists and dehumanizing us when Israel began carpet bombing Gaza leading to a genocide . For a few years since that moment, many Arab artists saw their work rejected, refused, or cancelled from shows, publications, and galleries. But in 2025, the propaganda against Arabs began to be debunked and the world recognized that Israel was in fact a colonial military occupation decimating Indigenous people, and curiously, we started receiving invitations to participate in the art world again.In the middle of last year, I was invited to exhibit my work at the Venice Biennale as part of their Personal Structures art exhibition. But unfortunately, I found myself needing to decline the invitation due to their separation between artistic practice and political reality: An expectation, stated and implied, that the work remain “apolitical.”For many artists, this is understood as an important recognition in one’s art career, a symbolic entrance into contemporary art history. Venice confers legitimacy, visibility, and, for many of us, validation from a historically extractive, colonial arts system. It also functions, like all major biennials, as an instrument of cultural diplomacy, soft power, and geopolitical storytelling. So a representation at the Venice Biennale as a Lebanese artist means a lot on a political scale.The word “apolitical” was used as part of a response that the Venice Biennale curator sent to justify their position regarding centering Israeli artists. It was an attempt to make explicit that engaging with the ongoing violence shaping the present moment, including the mass killing and destruction in Gaza, is a personal choice. That art exists without consequence, an elevated ideal that has the privilege of existing outside reality.I couldn’t tolerate pretending art was separated from politics, when Israel continues to bomb Lebanon daily, erase and sell Gaza, and murders Palestinians almost on a daily basis. Not when, just this February, Israel proposed to install a death penalty for the abducted Palestinians in Israeli jails with complete immunity. We are living through a time in which bombardment, starvation, displacement, and civilian death are documented in real time. Images circulate instantly; testimony is archived before bodies are buried. The evidence is not obscured by distance or ambiguity, but rather, is immediate, relentless, and impossible to ignore. Yet cultural institutions claim ignorance or worse, voluntary exclusion. In such a context, neutrality is not a passive stance but an alignment with injustice.Moral clarity is non-negotiable for me. It is my anchor in a time where global forces are unveiling their corruption for the world to see. In shock and despair, overwhelmed by the intensity of the crimes, many remain silent. Motionless. Like deers in the headlights. Hence, the safe label of remaining apolitical.But the myth of the apolitical artist has always depended on their proximity to power. It is a luxury position historically afforded to those whose bodies are not directly threatened by the carceral order. For many artists—particularly those shaped by colonization, occupation, exile, or racial violence—the political is not a thematic choice. It is the ground of existence itself.Arab women artists have shown me the path to moral clarity, integrity, and honor. The Palestinian American painter Samia Halaby has long argued that all art is political in its relation to society, whether acknowledged or not. For instance, Mona Hatoum’s sculptural language, often read through the lens of minimalism, is inseparable from histories of displacement and surveillance. The body remains present even when absent, reminding viewers that aesthetics do not transcend geopolitics.The Egyptian feminist writer Nawal El Saadawi warned with unmistakable clarity: “Neutrality in situations of injustice is siding with the oppressor.” Her words emerged from lived confrontation with imprisonment, censorship, and patriarchal state violence. Neutrality was never theoretical to her, it was lethal.Black feminist artists and thinkers have articulated the same truth. Audre Lorde’s assertion—“Your silence will not protect you”—dismantles the illusion that withholding speech preserves safety. Silence is participation in the maintenance of power. Lorraine O’Grady’s performances exposed how cultural institutions erase entire populations while claiming universality, revealing that visibility itself can be a political rupture. These perspectives converge on a single recognition: Art does not exist outside power structures. It either interrogates them or reinforces them.We remember artists who refused neutrality because their work altered the moral imagination of their time. Artists like Ai Weiwei, whose work centers politics and identity, go as far as putting their own bodies in danger. We remember the cultural boycott of apartheid South Africa, when artists refused lucrative opportunities rather than legitimize a racist regime. We remember Nina Simone transforming grief and rage into sonic resistance. We remember the Black Arts Movement insisting that aesthetics could not be detached from liberation.We also remember the artists who accommodated power. History is rarely generous toward them. The contemporary art world often performs political engagement while it structurally protects capital, donors, and institutional relationships behind closed doors. Calls for “complexity” or “nuance” frequently operate as ways to avoid taking positions that might threaten funding streams or geopolitical alliances. Requests for artists to remain apolitical are risk-management strategies that prioritize donors’ comfort.The insistence that artists claim they “do not know enough” to speak while mass civilian death unfolds is abdication. It mirrors political rhetoric that justifies violence through ideology, nationalism, or divine authority. Both rely on belief systems that absolve responsibility. The role of the artist is not to decorate power. It is to feel reality—to alchemize collective experiences into forms that expand perception rather than sterilize it.Art is essential precisely because we are living through rupture. But essential art is not decorative. It is not institutional ornamentation detached from consequence. It does not require erasing humanity in exchange for belonging to elite cultural circuits. Refusing the Biennale was not a heroic gesture. In fact, I had no desire to write this piece to begin with. It was just a form of moral clarity. Moral clarity some can live without, but unlike them, I refuse to become numb. I want to exist with a deep connection to my own humanity, and to feel it all.Including this moment that forces us to reckon with our own privileges and position. No exhibition, no platform, no symbolic prestige outweighs the responsibility of responding honestly to the conditions shaping our world. Participation under forced neutrality in accepting the presence of genocidal entities such as Israel would have required fragmentation — an agreement to pretend that art exists outside the systems producing suffering, including settler colonial violence and military occupation.It does not. And I cannot fake it."

}

,

{

"title" : "ICE Attacks Are a Food Sovereignty Issue",

"author" : "Jill Damatac",

"category" : "essay",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/ice-interference-is-a-food-sovereignty-issue",

"date" : "2026-02-24 11:26:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/ice_food_soveriegnty.jpg",

"excerpt" : "Food inequality, like the carceral state, is not a bug, but a feature.",

"content" : "Food inequality, like the carceral state, is not a bug, but a feature.California National Guard troops face off with protestors during a federal immigration raid on Glass House Farms in Camarillo, Calif. on July 10, 2025. Photo Credit: Blake Fagan via AFPIn June 2025, ICE agents walked into Glenn Valley Foods, a meat plant in Omaha, Neb. and detained roughly half the workforce. Production sagged to a fraction of normal: Producers were already strained by drought, thinned herds, and high cattle prices. On paper and in headlines, the Trump administration claimed an enforcement success; on the plant floor, workers stayed home, choosing to lose wages rather than risk returning. Beef processors warned that if raids became routine, they would buy fewer animals, and bottlenecks would pinch slaughterhouses and feedlots. The systemic shock emerged in the price of ground beef, which edged, at one point, towards seven dollars a pound. Still, raids were sold to voters as proof of control, even as they paid more for food and meals.ICE actions against food workers, already exhausted and criminally underpaid, have a demonstrable effect on sky-high food prices and our tax dollars: Raids further strain an already fragile, extractive food production and service system by not only further funding violent carceral systems, but also our fiscal ability to put food on the table. And while it’s clear that much needs to be changed when it comes to how we treat food workers–from livable wages and health insurance to legal protections and affordable housing –one thing has not been properly acknowledged. ICE interference shapes how we eat and our ability to have food sovereignty.By definition, food sovereignty is, first and foremost, a claim to power. It is the right of communities, including immigrant food workers, to decide how food is grown, who profits from it, and what it costs. True self-determination means the land and our labor serve everyone, rather than corporations or government agencies. It means the price of food stays low and steady enough that working-class households eat well, that profits are shared so that small farmers, migrant workers, and food workers can live with dignity and comfort. But this is far from the reality we face today: with grocery and restaurant bills rising and food workers one threat away from deportation, what we are left with is a food system benefiting corporate interests, flanked by a carceral force wearing a false claim to justice as a mask.Immigrant food workers carry the nation’s appetite on their shoulders: According to a 2020 study by the American Immigrant Council, over 20% of food industry workers are immigrants. Within agriculture, 40-50% of workers are undocumented on any given year, while in the restaurant industry, undocumented immigrants are 10-15% of the workforce. Their work is in our carts, fridges, and pantries, on our restaurant tables, takeout counters, and drive-throughs. Workers are keenly aware that ICE knows exactly where to detainthem to hit their arrest quota: in fruit orchards and vegetable farms, meat processing plants, egg barns, dairy plants, grocery stores, restaurant kitchens, and even the parking lots where they gather at dawn, hoping to find work for the day. With agents detaining and deporting workers regardless of immigration status or criminal record, workers are scared into staying home, giving up precious income just to live another day. Meanwhile, fields go unpicked, stores scramble to cover shifts, and kitchens stall. Crews thin out rather than risk being taken, or, as in the case of Jaime Alanís García, are killed while fleeing an ICE farm raid.These calculations between fear and courage in the face of aggression are not abstract to me; they’re personal. My father was an undocumented immigrant who worked nights stocking a cereal aisle. He was given thirty-two hours a week, just shy of full-time, so the grocery store could avoid providing health insurance. When a new manager began to ask employees for identification, my dad and other undocumented co-workers quit, leaving the store scrambling to find people willing to work for minimum wage, nearly full-time, with no healthcare. These violent acts move through the food chain under the guise of “rising prices,” a surcharge in our grocery carts and restaurant bills.The U.S. government has played with the lives of immigrant food workers many times before. Under President Herbert Hoover during the Great Depression, “Mexican repatriation” campaigns deported hundreds of thousands of Mexicans and Mexican Americans, many of them farmworkers recruited in boom years, as officials caved to white workers, who were both unwilling to cede the work to immigrants or to take on the low-paying farm jobs themselves. Filipino farmworkers, known as the Manongs, were treated similarly: in the 1920s and 30s, Filipino workers slept in crowded bunkhouses, were paid low wages, worked through illnesses such as tuberculosis, and were given no path to citizenship, even though the Philippines was then a U.S. territory. In January 1930, white mobs in Watsonville, Calif. hunted Filipino men, beat them, threw them off bridges, and shot and lynched them. Soon after, California banned marriage between Filipinos and white people, and Congress slashed Filipino immigration to a token quota. The food industry has long built itself on brown people’s labor while the law denied them basic human rights. At the root of it all is a sinister plantation logic: a nation’s wealth and abundance built on enslaved Black people’s labor and deprivation. It’s just new bodies in the fields, now.Today’s arrests and deportations are a continuation of this very logic: exploited migrant workers are still denied basic rights and protections while the food industry that employs them grows, year on year. Many lack legal status; many more live in mixed-status families. Using the excuse of “border security,” ICE and DHS agents press on that vulnerability by design. As a result, fear of ICE enforcement becomes a cost itself, narrowing what people can afford and where they can eat. These enforcements, carried out without input the food industry or local communities, and often against their will, directly impact our food sovereignty—how people determine the way food is grown, distributed, made, and served, as well as how workers within the food industry are paid and treated.Take summer 2025 as an example: ICE raids swept through produce fields around Oxnard in California’s Ventura County, arriving in unmarked vehicles (and sometimes helicopters) at the height of harvest. The raids spread, so crews went into hiding: one Ventura County grower estimated that roughly 70% of workers vanished from the rows almost overnight, leaving farms heavy with rotting produce and no one to pick it. Economists modeling removals of migrant farmworkers from California estimate that growers could lose up to 40% of their workforce, wiping out billions of dollars in crop value and raising produce prices by as much as 10%.These losses are passed on to communities and households, obfuscating why and how the increases happened in the first place. The American consumer is consequently exploited, too, absorbing the real labor cost of detentions and deportations. In Los Angeles, immigration sweeps in June 2025 hit downtown produce markets and surrounding eateries; vendors called business “worse than COVID” as customers vanished and supplies wasted away in storage. In January 2026, along Lake Street in south Minneapolis, immigrant-run spots like Lito’s Burritos and stalls at Midtown Global Market, a popular food hall in downtown Minneapolis, saw revenue plunge due to ICE enforcement, forcing them to cut hours, or close altogether. In nearby St. Paul, Minn., El Burrito Mercado shut down after its owner watched agents circle the building “like a hunting ground.” Meanwhile, four ICE agents ate at El Tapatio, a restaurant in Willmar, Mn. Hours later, they returned after closing time to arrest the owners and a dishwasher. Hmong restaurants and Mexican groceries across the Twin Cities have gone dark for days or weeks at a time, suffocating the local economy, leaving consumers with shrinking access to food, and small business owners with no revenue while their employees go unpaid.If food sovereignty means real control over how food is grown, distributed, and accessed, it must begin with the safety of the workers holding the system up. Workers’ wellbeing is not ornamental: it is the precondition for steady harvests, stable prices, and an affordable Main Street. Federal and state legislation must build strict firewalls between labor and immigration enforcement so that workers can file complaints, call inspectors, or take a sick day without fear. Laws can enforce and extend safety protections, wage standards, and the right to unionize. This can only happen with comprehensive immigration reform: A durable legal status and a path to citizenship for food and farmworkers would help immigrant families break the old pattern of being extracted for labor while being denied the basic right to stability.There are also infrastructures that must be abolished to truly achieve food sovereignty: specifically, the burgeoning immigration detention industrial complex. The Big Beautiful Bill allocated $75 billion dollars, spread over four years, to ICE, funding the expansion of private prison facilities. Alongside the nation’s existing prison industrial complex, the immigration detention industrial complex has become a key economic driver, albeit one that benefits only a few, such as shareholders in CoreCivic and Geo Group, two of the nation’s biggest private prison companies.Food inequality and lack of food sovereignty, like the carceral state, are not bugs, but features: soaring food, housing, and healthcare costs, voter discontent, and public unrest form a feedback loop, reinforcing the manufactured narrative scapegoating immigrant and migrant workers. If enough Americans believe that immigrants are to blame for the high prices in grocery stores and restaurants, no one will pause long enough to scrutinize the corporations (and owners) who stand to profit.Should legislators have the courage to change the infrastructure that allows these inequities to occur, the hands that harvest, pack, cook, serve, and wash would be fairly recognized as part of the nation they feed. Because fear and imprisonment should never be priced into the dinner table. Everyone can—and should be able to—eat."

}

]

}