Digital & Print Membership

Yearly + Receive 8 free printed back issues

$420 Annually

Monthly + Receive 3 free printed back issues

$40 Monthly

Muriel Ahmarani Jaouich

EIP: Tell us about your Lebanese / Armenian heritage and how it influences your artwork.

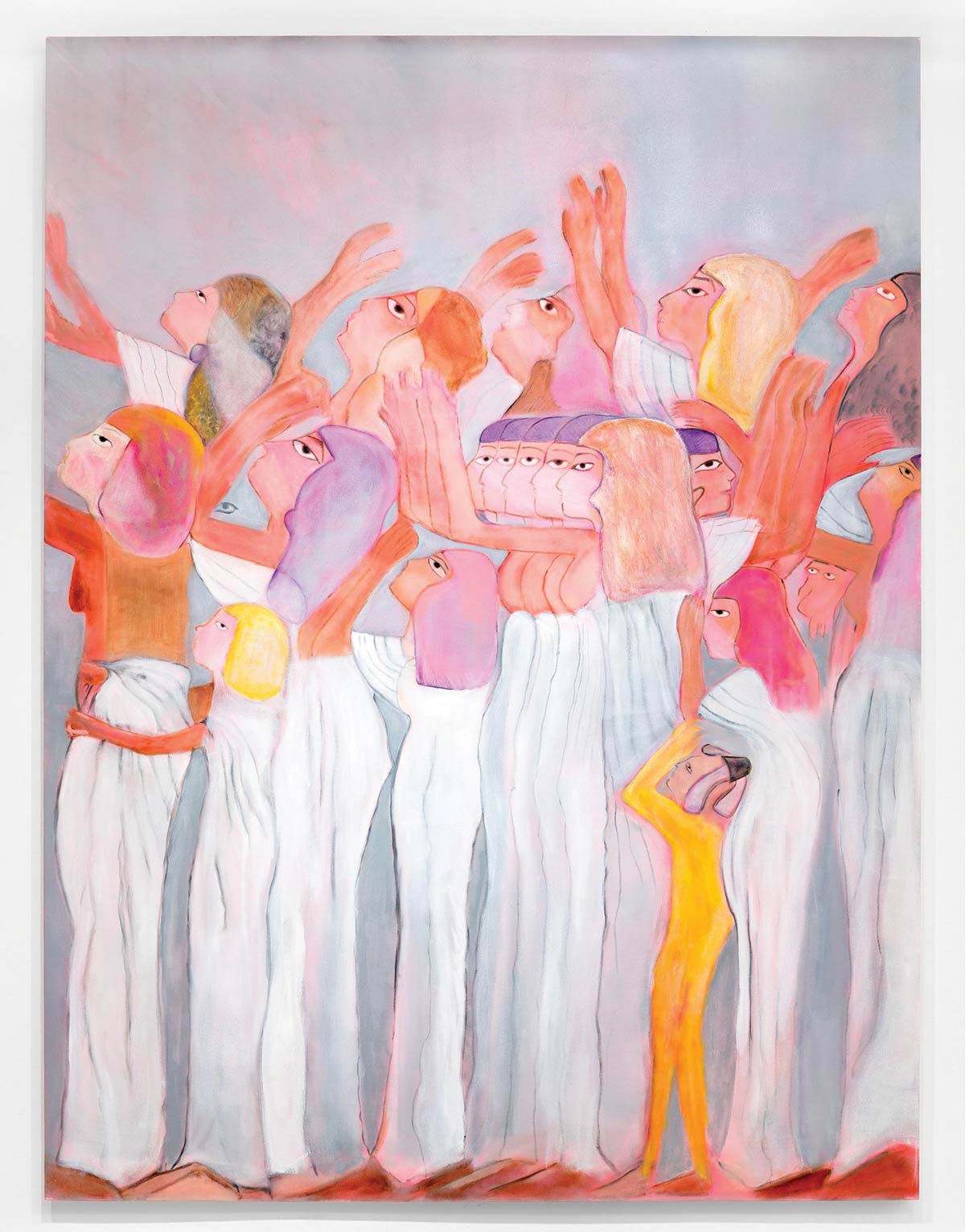

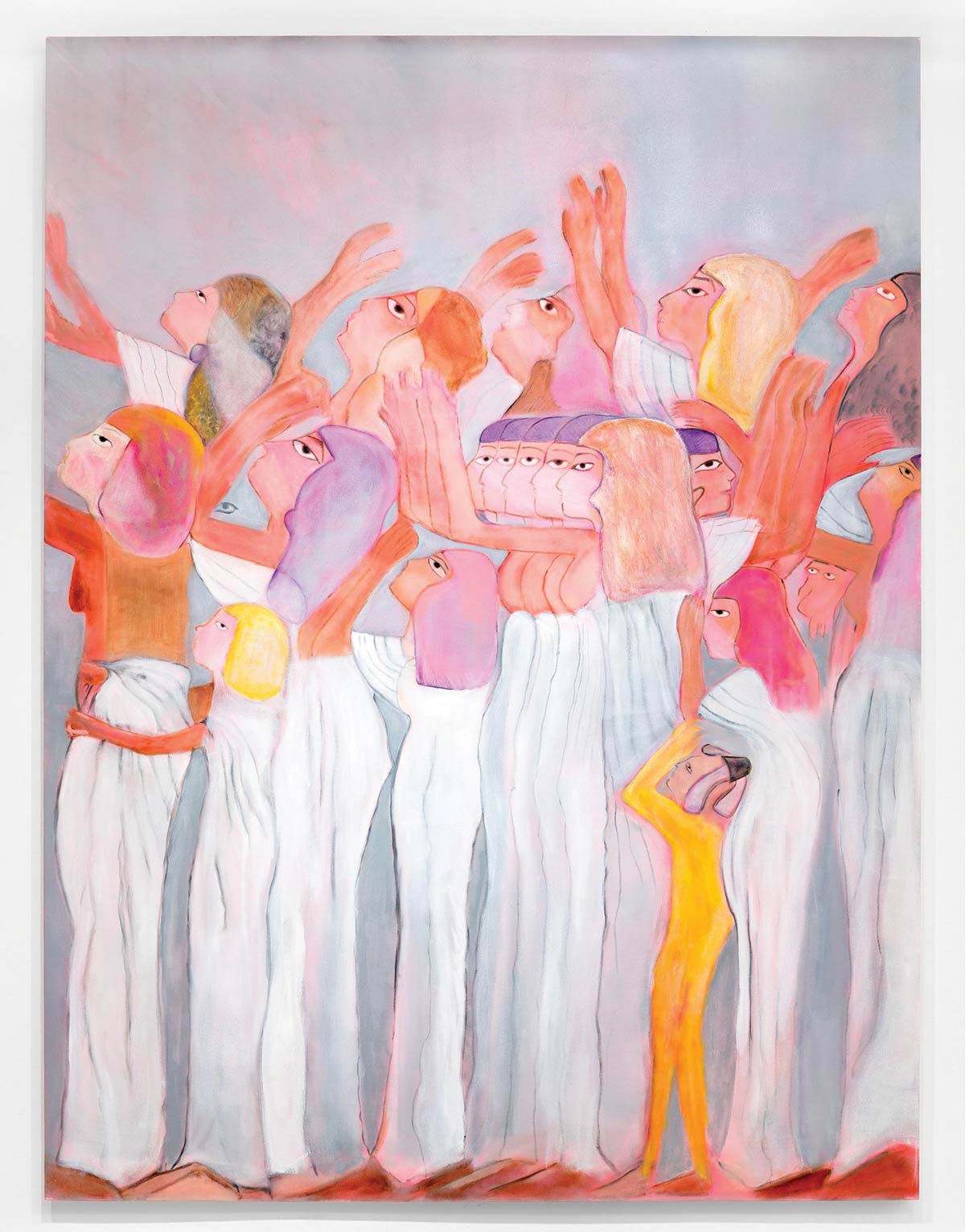

MURIEL: As a Canadian artist of Armenian, Egyptian and Lebanese descent, my paintings focus on genealogy, intergenerational trauma and historical violence. In my work, I create a narrative based on the history of my family; one of diaspora, immigration, and genocide. My maternal grandparents are survivors of the Armenian Genocide of 1915-1923. My grandfather lost his parents and thirteen siblings, who were massacred in 1915 in Mardin, Turkey. He and one brother survived and were exiled to Alexandria, Egypt, though their family originally came from Baghdad, Iraq. My grandmother also lost her parents and sister in Mardin, Turkey. She fled by boat and was exiled to Alexandria, where she lived in an Armenian orphanage. On my father’s side, my grandfather’s side have been in Alexandria, Egypt, since the late 1800s, though the family originally comes from Deir El Amar in Lebanon. On my grandmother’s side, there is also Syrian and Coptic Egyptian heritage in my paternal lineage.

My research is based on oral histories, photographic archives and objects bequeathed to me. I draw on archival records of family albums, memories, secret histories, gaps, silences or moments shared through oral interviews. I become a receptacle. I transform this knowledge and create narratives using memory and imagination. When stories and memories are subjected to time, the narratives become blurred, on the borderline between reality and fiction. My images serve as metaphors for the impact of intergenerational trauma. Decolonizing is about recognizing and naming the worldview forced, reinforced, and enforced by this colonial experiment and picking up the teachings and practices of our ancestors. The work speaks of ancestral grief. Such grief work invites an ongoing practice of going deep, caring, and listening. Dealing with the undigested anguish of our ancestors frees us to live our present lives. In turn, it can also relieve ancestral suffering in the other world.

EIP: What did the very beginning of your artist journey look like?

MURIEL: Pursuing an artistic path is something I could never have imagined, especially with parents who immigrated from Lebanon and Egypt and had to rebuild their lives from the ground up. I was raised to follow a traditional path, becoming either a doctor or dentist. Instead, I ended up working for companies in Silicon Valley and later for nonprofits like UNICEF. But something always felt off. Due to my own trauma and a lot of dissociation, it took a long time to reconnect and find my path. Therapy and incredible meditation teachers like Daryl Lynn Ross and Pascal Auclair were instrumental in that journey. I never gave up on searching for something that resonated more deeply, and slowly, it was revealed to me. My spiritual practice is deeply intertwined with my art; they support and enhance each other in a symbiotic way. Coming from a faith-oriented background on my maternal side, I grew up attending Armenian church every Sunday. Alongside this, I pursued my own spiritual exploration by studying Buddhist philosophy and participating in extensive meditation retreats,

including one six-week retreat in silence. These experiences have profoundly shaped my worldview and way of life. My paintings are an extension of my sensitivity, living through me as I create. I feel profoundly guided and supported by my ancestors during the painting process.

EIP: How would you compare your artwork from when you just started to your work in the present moment? How did the Egyptian influence in your current works come about?

MURIEL: The real turning point came when I embarked on my MFA journey. Here’s how it unfolded…

At the start, my focus was on understanding and reconstructing the historical memory of the Armenian genocide through both personal and collective perspectives. I wanted my artistic research to generate new forms of knowledge. Through painting, I explored the potential of rebuilding personal and collective memory around the traumatic aftermath of the genocide. I also aimed for the work to play a political role, using humor to tell an alternative narrative rooted in my own life and field experiences.

I engaged in oral history-based research, delving into matrilineal stories of mothers and daughters within the context of family histories. My mother’s oral narratives became a gateway to using the familiar as a tool for uncovering the unknown. I sought to link personal and familiar experiences to something broader—collective, social, and far beyond my individual story. My mother, Anahid, shares her name with the Armenian goddess of fertility, healing, wisdom, and water. This prompted me to ask: Does the study of goddesses in Armenian mythology and other myths help us understand the dynamics between women, power, and spirituality? What layers of memory and patriarchal violence can be uncovered and discussed?

My iconography evolved dramatically in my second year, during what I call the “summer of sorrows” in 2021. My father became seriously ill and lost the ability to speak. His voice’s disappearance urged me to understand where he came from. His slow decline stirred a deep need within me to integrate my Egyptian heritage into my work. From an early age, I was exposed to Ancient Egyptian art, including painting, sculpture, and papyrus drawings, through my paternal grandparents who were still living in Alexandria during my childhood. I also realized that Alexandria, Egypt was where my maternal grandparents sought exile from Mardin. Egyptian iconography became my safe space, shaping the next series of paintings.

My Armenian-Egyptian-Lebanese heritage, along with the long- standing conflicts between the West and the Middle East, deeply influence my work. I’m interested in critiquing the ongoing forces of colonization and highlighting the value of cultural artifacts that have been lost, looted, or destroyed, as well as the human toll of continued violence. I see my paintings as a transformative force, capable of moving us into spaces where we can reclaim our power.

{

"article":

{

"title" : "Muriel Ahmarani Jaouich",

"author" : "Muriel Ahmarani Jaouich",

"category" : "interviews",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/global-resistance-art-muriel",

"date" : "2025-02-04 15:33:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/muriel-3.jpg",

"excerpt" : "",

"content" : "EIP: Tell us about your Lebanese / Armenian heritage and how it influences your artwork.MURIEL: As a Canadian artist of Armenian, Egyptian and Lebanese descent, my paintings focus on genealogy, intergenerational trauma and historical violence. In my work, I create a narrative based on the history of my family; one of diaspora, immigration, and genocide. My maternal grandparents are survivors of the Armenian Genocide of 1915-1923. My grandfather lost his parents and thirteen siblings, who were massacred in 1915 in Mardin, Turkey. He and one brother survived and were exiled to Alexandria, Egypt, though their family originally came from Baghdad, Iraq. My grandmother also lost her parents and sister in Mardin, Turkey. She fled by boat and was exiled to Alexandria, where she lived in an Armenian orphanage. On my father’s side, my grandfather’s side have been in Alexandria, Egypt, since the late 1800s, though the family originally comes from Deir El Amar in Lebanon. On my grandmother’s side, there is also Syrian and Coptic Egyptian heritage in my paternal lineage.My research is based on oral histories, photographic archives and objects bequeathed to me. I draw on archival records of family albums, memories, secret histories, gaps, silences or moments shared through oral interviews. I become a receptacle. I transform this knowledge and create narratives using memory and imagination. When stories and memories are subjected to time, the narratives become blurred, on the borderline between reality and fiction. My images serve as metaphors for the impact of intergenerational trauma. Decolonizing is about recognizing and naming the worldview forced, reinforced, and enforced by this colonial experiment and picking up the teachings and practices of our ancestors. The work speaks of ancestral grief. Such grief work invites an ongoing practice of going deep, caring, and listening. Dealing with the undigested anguish of our ancestors frees us to live our present lives. In turn, it can also relieve ancestral suffering in the other world.EIP: What did the very beginning of your artist journey look like?MURIEL: Pursuing an artistic path is something I could never have imagined, especially with parents who immigrated from Lebanon and Egypt and had to rebuild their lives from the ground up. I was raised to follow a traditional path, becoming either a doctor or dentist. Instead, I ended up working for companies in Silicon Valley and later for nonprofits like UNICEF. But something always felt off. Due to my own trauma and a lot of dissociation, it took a long time to reconnect and find my path. Therapy and incredible meditation teachers like Daryl Lynn Ross and Pascal Auclair were instrumental in that journey. I never gave up on searching for something that resonated more deeply, and slowly, it was revealed to me. My spiritual practice is deeply intertwined with my art; they support and enhance each other in a symbiotic way. Coming from a faith-oriented background on my maternal side, I grew up attending Armenian church every Sunday. Alongside this, I pursued my own spiritual exploration by studying Buddhist philosophy and participating in extensive meditation retreats,including one six-week retreat in silence. These experiences have profoundly shaped my worldview and way of life. My paintings are an extension of my sensitivity, living through me as I create. I feel profoundly guided and supported by my ancestors during the painting process.EIP: How would you compare your artwork from when you just started to your work in the present moment? How did the Egyptian influence in your current works come about?MURIEL: The real turning point came when I embarked on my MFA journey. Here’s how it unfolded…At the start, my focus was on understanding and reconstructing the historical memory of the Armenian genocide through both personal and collective perspectives. I wanted my artistic research to generate new forms of knowledge. Through painting, I explored the potential of rebuilding personal and collective memory around the traumatic aftermath of the genocide. I also aimed for the work to play a political role, using humor to tell an alternative narrative rooted in my own life and field experiences.I engaged in oral history-based research, delving into matrilineal stories of mothers and daughters within the context of family histories. My mother’s oral narratives became a gateway to using the familiar as a tool for uncovering the unknown. I sought to link personal and familiar experiences to something broader—collective, social, and far beyond my individual story. My mother, Anahid, shares her name with the Armenian goddess of fertility, healing, wisdom, and water. This prompted me to ask: Does the study of goddesses in Armenian mythology and other myths help us understand the dynamics between women, power, and spirituality? What layers of memory and patriarchal violence can be uncovered and discussed?My iconography evolved dramatically in my second year, during what I call the “summer of sorrows” in 2021. My father became seriously ill and lost the ability to speak. His voice’s disappearance urged me to understand where he came from. His slow decline stirred a deep need within me to integrate my Egyptian heritage into my work. From an early age, I was exposed to Ancient Egyptian art, including painting, sculpture, and papyrus drawings, through my paternal grandparents who were still living in Alexandria during my childhood. I also realized that Alexandria, Egypt was where my maternal grandparents sought exile from Mardin. Egyptian iconography became my safe space, shaping the next series of paintings.My Armenian-Egyptian-Lebanese heritage, along with the long- standing conflicts between the West and the Middle East, deeply influence my work. I’m interested in critiquing the ongoing forces of colonization and highlighting the value of cultural artifacts that have been lost, looted, or destroyed, as well as the human toll of continued violence. I see my paintings as a transformative force, capable of moving us into spaces where we can reclaim our power."

}

,

"relatedposts": [

{

"title" : "Bad Bunny's Halftime Show Is About So Much More Than Symbolism",

"author" : "Zameena Mejia",

"category" : "essays",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/bad-bunnys-halftime-show-is-about-so-much-more-than-symbolism",

"date" : "2026-02-09 09:10:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/Cover_EIP_Bad_Bunny_SB.jpg",

"excerpt" : "Joy Is an Equal Part of Protest as Rage",

"content" : "Joy Is an Equal Part of Protest as RageOn Sunday night, Bad Bunny transformed the Super Bowl LX field in Santa Clara, Calif. into an homage to the Puerto Rican countryside for a historic, almost entirely Spanish set. Weaving through sugar cane fields and scenes of everyday life in Puerto Rico, he carried a football that said, “TOGETHER, WE ARE AMERICA” as he sang a career-spanning medley of his own songs, also splicing in a few classic hits from some of reggaeton’s pioneering voices like Tego Calderón, Don Omar and Daddy Yankee, and a surprise salsa rendition with Lady Gaga of 2025’s most popular song “Die With a Smile.” As red, white, and blue fireworks—specifically a light shade of blue similar to that seen in Puerto Rico’s independence flag—shot up around Bad Bunny, the Puerto Rican artist unabashedly elevated the pride, joy, and struggles that come with being Latino in today’s political climate and reminded us that America is comprised of a full continent of sovereign nations and occupied territories–not just the U.S.For the fans who endearingly coined Sunday’s event “Benito Bowl,” this moment is about so much more than seeing the world’s most popular Spanish-language superstar take the stage: It’s about seeing Bad Bunny leverage his privilege to defend Latinos’ dignity, push back on the U.S. government’s draconian anti-immigrant actions, and rally the American public around something far more fortifying than violence: music and art.Bad Bunny’s performance comes at a time when Latinos and immigrants of other ethnicities in the U.S. are being disappeared, detained, and deported in historic numbers. They have been unable to go to work, send their kids to school, go to their houses of worship, or even attend mandatory immigration hearings without the fear of being targeted by federal law enforcement for the color of their skin or ability to speak English, regardless of their immigration status. In the past few weeks alone, Americans exercising their constitutional rights to protest and document ICE activity have led to the shocking deaths of U.S. citizens Renee Nicole Good and Alex Pretti in Minneapolis, Minn., offering a sobering example of how ICE violence can (and will) affect all of the people in this country, not just Latinos. This does not even begin to cover how American imperialism is affecting Latinos abroad. It has only been a few weeks since the U.S. government attacked Venezuela (and gained more oil control, as a result), captured President Nicolás Maduro, invoked the Monroe Doctrine, threatened to intervene in additional Latin American nations, and continues to carry out deadly attacks on alleged drug boats in the Caribbean Sea and the Eastern Pacific.Holding this dichotomy–elation for the possible, humane future Bad Bunny represents, and the unmitigated state violence America has imposed on Latinos–is not easy. When “el conejo malo,” as Bad Bunny is also known in Spanish, appeared in a gray beanie hat with bunny ears at the halftime show press conference last week, it was difficult to not think back to just a couple of weeks ago when the image of 5-year-old Liam Conejo Ramos went viral as he stood alone circled by federal agents, wearing a bright blue bunny hat when ICE detained him, and abducted him from Minneapolis to an ICE detention facility in Dilley, Texas. (Liam’s family, лoriginally from Ecuador, had entered the country legally and were in the middle of an active asylum case, but in being apprehended, they were denied their Constitutional right to due process, which applies to everyone in the U.S., regardless of immigration status.)But, at a time when Latinos have been threatened with deportation just for speaking Spanish, Bad Bunny’s ascent to global stardom has reinforced Spanish as a language of resistance. Just three years after Bad Bunny’s first-ever Grammy Awards performance of Un Verano Sin Ti, he won the evening’s highest honor, Album of the Year, at the 2026 Grammys for his most political album yet, Debí Tirar Más Fotos. Importantly, though, he gave his acceptance speech almost entirely in Spanish, except for one message in English:“I want to dedicate this award to all the people that had to leave their homeland, their country, to follow their dreams,” he said.Here, Bad Bunny wasn’t just talking about Latinos; he was talking about everyone who has suffered under the oppression of white colonialism. And though Bad Bunny is first and foremost a celebrity and not our savior—for we must always save ourselves—this moment summarized a powerful, collective narrative shift that’s taking place in the U.S.: one in which the anti-immigrant sentiments expressed by the Oval Office feel completely out of step with the future that Americans are demanding. A future where art and music can be used for political good. A future where people can uphold the values of a democracy that includes and represents Latinos and immigrants of all backgrounds.Photo Credit: Eric RojasLeading up to the Super Bowl, anti-ICE posters have been plastered around San Francisco featuring unofficial artwork of el Sapo Concho—an illustrated toad character from Debí Tirar Más Fotos—with the words “chinga la migra” and “ICE out” in bold red and white words. In an ode to the communities across the U.S. who have formed rapid response networks and use red whistles to alert neighbors of ICE activity, the unofficial Sapo Concho also wears a whistle around its neck. Protestors have even dressed up as the album mascot, wearing “chinga la migra” shirts at parties around the Bay Area. Despite the NFL’s recent statements that denied there would be any ICE presence outside of the Super Bowl, Latinos in the Bay Area still feel distrust and fear.Up until this point, the halftime show marked Bad Bunny’s only Debí Tirar Más Fotos concert in the U.S. In 2025, he announced he had excluded the mainland U.S. from his world tour out of concern that ICE officers would target, detain, and deport his fans.And he was right. From the moment Bad Bunny made his Super Bowl Halftime show announcement in September 2025, right-wing conservatives doubled down on inciting fear. Within a week of the news, Kristi Noem, head of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), said she would ensure ICE presence outside of the Super Bowl. DHS adviser Corey Lewandowski alleged that Bad Bunny hates America. President Donald Trump denounced Bad Bunny’s role, first claiming to not know who the Grammy-award-winning artist was, and later calling the choice “ridiculous” and “terrible,” claiming that “all it does is sow hatred.”Yet it is the right wing that has spent months sowing division among Americans, asserting that Bad Bunny—born Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio, a U.S. citizen in the unincorporated U.S. territory of Puerto Rico—is “anti-American” and criticized the NFL’s decision to platform an artist who mainly sings in Spanish (which is the most commonly spoken non-English language in the U.S). In response, MAGA conservatives backed a competing halftime show created in protest against Bad Bunny and headlined by country rock singer Kid Rock.At worst, Bad Bunny has used his music to hold up a mirror to Trump’s administration since his first term in office. During a 2017 benefit concert for post-Hurricane Maria relief for Puerto Rico, Bad Bunny made and wore a shirt indirectly targeted at Trump that said, “¿Tu eres twitero o presidente?” which translates to “Are You a Tweeter or President?” In his 2020 song “Compositor del Año,” he rapped in defense of the Black Lives Matter movement, implored young people to vote, and said “there are more important things like fighting for the rights of immigrants,” all while calling out the president’s inaction. And despite his global popularity, Bad Bunny’s political stances remain a significant departure from mainstream political values, especially among the traditionally conservative, increasingly right-leaning Latinos in the U.S. and across Latin America. His ability to reach new audiences and draw connections between distant communities’ struggles by highlighting issues happening in Puerto Rico are prime examples of how global artists can use their music to challenge the political status quo and bring about progressive change.To non-Spanish speakers, Bad Bunny’s blend of salsa, reggaeton, dembow, bomba y plena, and rap makes for music that’s fun and catchy. Lyrically, though, it’s clear how he uses his art to send a loud message. Debí Tirar Más Fotos and its accompanying music videos tackle gentrification and displacement of Puerto Ricans on the island and its diaspora, honor Puerto Rico’s anticolonial heroes and pro-independence movements, and celebrate the resistance. On the song “Lo Que Le Pasó a Hawaiʻi,” which Puerto Rican crooner Ricky Martin performed at the halftime show, he connects the shared struggles U.S. colonization has brought upon Puerto Rico and Hawaii.Beyond American politics, Bad Bunny’s success as a politically forward Caribbean and Puerto Rican artist carries a deeper meaning within the Latino community. Historically, people from Caribbean countries have been marginalized and discriminated against for being largely racialized as Black—as a result of the legacy of slavery in the Caribbean—as well as for having vastly distinct accents from the rest of Latin America due to centuries of being subjugated by colonial powers. Bad Bunny’s success over the past decade brought about newfound attention on Puerto Rican and Caribbean genres, art, fashion, vocabulary, and history.For the many Caribbean Latinos who grew up being told their Spanish was “incorrect” or “not good,” seeing Bad Bunny’s ascent to mainstream TV programming, films, and the overall cultural zeitgeist – without having to codeswitch or change his accent – is validating. White supremacist ideals are still baked into many parts of Latino culture because of centuries of European colonization: for instance, in the way accents are forcibly “corrected” (whitewashed) in order to be deemed professional. Or in the way that traditionally Black Latin music genres like bachata, reggaeton, salsa, and dembow have historically struggled to achieve commercial success until they were extracted from Caribbean countries and performed by white and light-skinned artists from other parts of Latin America or Spain.Through his latest projects, Bad Bunny has invited the world to see Puerto Rico and the Caribbean in its totality—as so much more than just what can be consumed or extracted from our cultures.Photo Credit: Eric RojasThere’s a curious moment in Bad Bunny’s 2025 music video for “NUEVAYoL,” where he imagines a world where Trump apologizes to the Latino community in the music video: “I made a mistake. I want to apologize to the immigrants in America, I mean the United States, I know America is the whole continent,” a Trump impersonator says over a radio. “I want to say that this country is nothing without the immigrants. This country is nothing without Mexicans, Dominicans, Puerto Ricans, Colombians, Venezuelans, Cubans.” Without skipping a beat, those listening to this message shut it off and carry on with what they were doing.The success of Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl halftime show feels like an extension of this very sentiment. It reminds us that our collective strength is more powerful than the divisive, hateful forces that try to silence us. As the NFL capitalizes on Bad Bunny’s stardom, a move that makes sense as the league aims to reach more Latino consumers and continue to push into international markets, it’s important to remember that the NFL needed Bad Bunny more than Bad Bunny needed them—and the Puerto Rican artist likely knows this. He not only brought his Debí Tirar Más Fotos party to the world’s biggest TV event, but he also demonstrated that joy is equally a part of protest as rage. Because nothing makes the opposition more upset than indifference. Than the dissent that it takes to go on living."

}

,

{

"title" : "A Call to Arms",

"author" : "Jeremiah Zaeske",

"category" : "essays",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/a-call-to-arms",

"date" : "2026-02-03 11:17:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/1000013371.jpeg",

"excerpt" : "Birds perch on the gaps in barbed wire",

"content" : "Birds perch on the gaps in barbed wireBeckoning us to join themWater trickles through the obstruction in its path as if it were nonexistentWe have forgotten that we are waterVines weave a tapestry through metalIf trees cannot find a gap in the fence they will squeeze their way through,engulf it,absorb the border within themselvesThis is a call to armsLOVEI want my love to break through glassI want it to uproot the weeds that have grown in my heart as it picks through yoursI want it to burn through every piece of fabric stained with bloodLove was never a pacifistWhere there is evil there will also be two kinds of joyOne that revels in the misery,grinning faces posing with dead bodieswhile others look on in silence growing numbBut love is the joy of resilienceThe joy of knowing we will always need eachother enoughto tear down the walls and reach out our handsin spite of everything, even deathTo grab at the roots of ourselvesand plant flowers in place of the hate that’s been sown,though the stems may have thornsThis love will be the callouses born from fighting our waythrough rough brick and sharp glass edges,but they’ll just make it that much softer when palm meets palmThis love will be the fertilizer for a garden of scar tissue,never again to be buried under earth and thick skinThis love will be the seeds taking rootafter a long cold winter,sprouting from our chests and cracks in the pavementto greet a long-awaited springA NURTURING DEATHShot-gun weddingDrive-by baby showerClose-range baptismBurn down the forest,the church and the steepleThe baby’s gender is Destruction,Death, andPrimordial ChaosWe are unlocking the worlds they shut away,beyond the talons of textbook definitions,worlds they swore could never existworlds they swore to destroyWe’re pulling out fragmentsthrough the cracked open doorto fill the potholes and cracked cementof our bodymindsouls,to make salve for the woundsThe ones they claimed were pre-existingand unfillableand unfixableand “who’s going to pay for that?”We are toppling immovable fortresseslimb by limb,peeling off skin and tearing through tendonto reveal the brittle forgeries of boneWe are de-manufacturing wildernessNot just free reign for the treesor even all the life they hold,but regrowth for the village of Ahwahnee,birds pecking out the eyes of campers at YosemiteWhat remains will be fed back into the ecosystem,into the bellies of bears and mountain lions,swallowed by insects and earthuntil it’s decayed enough to fertilize the soiland grow foodmedicinelifeA rebirthA nurturing death"

}

,

{

"title" : "This is America: Land of the Occupied, Home of the Capitalists",

"author" : "Mattea Mun",

"category" : "essays",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/this-is-america",

"date" : "2026-02-03 11:11:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/ice-protest-2-gty-gmh-260130_1769810312461_hpMain.jpg",

"excerpt" : "They tell us we live in the land of the free. They declare, “we the people,” and we assume they mean us when we were only ever defined – designed – to be the fodder to build their “life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness.”",

"content" : "They tell us we live in the land of the free. They declare, “we the people,” and we assume they mean us when we were only ever defined – designed – to be the fodder to build their “life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness.”On a Thursday, a 2-year-old girl returned home from the store with her father, Elvis Tipan-Echeverria, when unknown, masked agents trespassed onto their driveway and smashed the window in. In the name of defending the pursuit of happiness, she, with her father, was shoved into a car with no car seat and placed on a plane to Texas. This little girl was eventually returned to her mother in Minnesota; her father – still imprisoned in the land of the free.In the name of liberty, 5-year-old Liam Ramos, with his father, was seized and flown away from his mother and his home to sit in a detention facility in Texas, where his education will halt, his freedom is non-existent, and his pursuit of happiness – denied.In the name of life, Chaofeng Ge was “found” hanging, dead, in a shower stall in detention, his death declared a suicide though his hands and feet were bound behind his back, a fact evidently not deemed worthy of being initially disclosed. Geraldo Lunas Campos was handcuffed, tackled and choked – murdered – in detention, in an effort to “save” him. Victor Manuel Diaz, too, was “found” dead, a “presumed suicide,” the autopsy – classified.American voters like to declare that our present reality isn’t “what they voted for,” despite the fact that one of Donald Trump’s campaign promises in the 2024 election was to “carry out the largest domestic deportation operation in American history,” inevitably according to xenophobic and white supremacist lines. What many of us fail to remember is that this is not the first time we have voted for this. Indeed, I am not confident there is any point in American history that we have not collectively voted for this, regardless of so-called “party lines.”We Have Been Here BeforeWhile the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) was founded in 2003, slavery and genocide predated the very Constitution of the United States, the bodies of African Americans and Indigenous Americans brutalized and broken in the service of laying the foundations of (white) American wealth. Though slavery was “abolished” in 1865 by the 13th amendment, this did not end the policing of racialized bodies.During the Reconstruction era, convict leasing and black codes preserved the conditions and social hierarchy that existed under slavery. Moreover, any legal rights afforded Black Americans were and still are persistently undermined by their inferior social caste, whereby their deaths and suffering at the hands of law enforcement, the healthcare system and other Americans often goes unprosecuted and/or unpunished.Within WWII-era Japanese internment camps, inmates were stripped of their freedom to move, subjected to harsh living conditions and coerced to partake in underpaid, unprotected labor.The Lucrative Business of Slavery and its Bipartisan ProfiteersTo this day, the prison system remains a potent vestige of slavery, again for the sake of profit, as inmates’ human rights are systematically liquidated. As early as the 1980s, the federal government has contracted for-profit prison corporations to operate federal detention facilities. Today, over 90% of ICE detention facilities are operated by for-profit prison corporations as of 2023, a figure which increased from 79% within Biden’s presidency alone.These trends, in conjunction with the ongoing mass detainments of America’s people of color, are not surprising when we consider the immense profits our politicians and some Americans stand to gain, made possible by the continuous enslavement of racialized bodies.Our bodies are their profit.Under the Voluntary Work Program, forced carceral labor is codified, whereby detainees are to receive “monetary compensation of not less than $1.00 per day of work completed,” their “voluntary” labor absolving them of legal employee protections, such as minimum wage. And although ICE affirms that “all detention facilities shall comply with all applicable health and safety regulations and standards,” there is confusion as to how these standards are checked, especially when we consider the Trump administration closed the DHS’s Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties in March 2025.Nevertheless, several lawsuits and detainee testimonies attest to the fact that the work program is rarely voluntary, the survival of themselves and the facilities imprisoning them hinging upon their labor and minimal income. Indeed, many detainees are expected to purchase their own basic products, such as toilet paper and soap. Other detainees recall being threatened with solitary confinement, poorer living conditions and material punishment if they refused to work. Martha Gonzalez was denied access to sanitary pads when she requested a day off work, demonstrative of a larger pattern of ICE’s refusal to provide hygiene products and spaces to maintain one’s hygiene in a dignified manner.In 2023, GEO Group, one of the largest for-profit prison corporations, made over $2.4 billion in revenue, of which ICE, as their largest customer, accounted for 43%, or $1.04 million. ICE also accounted for 30% of CoreCivic’s – another large for-profit prison corporation – revenue. Thus, our bodies enable these companies to amass hundreds of millions in profit.Incidentally, CoreCivic and GEO Group are among the private prison companies that contribute the most to political campaigns, parties and candidates. In the 2024 election cycle, GEO Group gave $3.7 million in contributions, including $1 million to Make America Great Again Inc, while CoreCivic provided roughly $785,000 in contributions. While Republican candidates and committees have been the recipient of the large majority of these funds in recent years, Democrats and the Democratic Party are also guilty of accepting funding from these corporations, among others. In the 2024 cycle, CoreCivic contributed $50,000 to the Democratic Lieutenant Governors Association and Kamala Harris received $9,500 from GEO Group.The opportunities for profit extend even further beyond the U.S.’s borders as more and more nations are gradually entering deals to imprison noncitizen deportees coming from the U.S. In November, $7.5 million was paid out to Equatorial Guinea for this purpose. Alongside other Latin American countries like Costa Rica and El Salvador, Argentina is also rumored to strike their own deal with the U.S.Our bodies are their profit.The ongoing ICE campaign stands as a bipartisan issue, mirroring the ways our country’s deepest social inequalities have been repeatedly upheld on all sides of the political aisle throughout our history.The Occupied Mind and BodyMoreover, the policing of racialized bodies does not merely pertain to the body alone as a site to be moved and removed. Rather, this violence is also waged in our social spaces, in our fears and inside of our bodies.In the classroom, our curriculums hardly, if at all, represent a version of events where we existed and meanwhile the current administration actively tries to erase any part of history we are given a claim to. Such initiatives, too, have been supported for generations, reflected in the 150-year period Indigenous American and Hawaiian children were forcibly taken from their homes and sent to boarding schools designed to facilitate their assimilation and more seamless theft of their native lands.In our social spaces and lives – if not yet brutally taken – liberty and the pursuit of happiness is not ours for the taking. We are perpetually told under what conditions our movement is permissible. Decades of redlining have, in many ways, preserved segregation and pooled the best resources for the white and the wealthy to the detriment of communities of color.But even this is not enough.They police us from the inside, too. In exchange for gifts like food and photographs of her daughter, a Nicaraguan woman was subjected to have sex with a now former ICE officer whilst in detention. A “romantic relationship,” according to federal prosecutors. Our suffering is still romanticized even when guilt has been assigned. What they still do not realize is that there is no place for romance to reside so long as we remain shackled, our bodies – looted.From the inside, they forcibly remove our reproductive organs, then and now. Many of us were among the 70,000 forcibly sterilized in the 20th-century, deemed “unfit” to reproduce. As we speak, 32% of surgeries performed in ICE detention facilities are performed without proper authorization, and there are reports of mass hysterectomies being exacted behind closed doors.They dictate our movements, lock us up, take our insides out, inject their fantasies onto and into our bodies, deprive us of our right to learn and to work and to live. And even if they have not yet come bounding at our doorstep, we lie anxiously in wait for the moment our past may catch up with us and seep, once again, back into our present.And yet, they have the audacity to say that it is by our hands that we are dying; that if only we had lived and loved differently, things wouldn’t be this way. In the name of safety and peace, they force our bodies into hiding or otherwise out onto the streets, despite the fact that only 5% of us have been implicated in a violent crime. In the name of safety, they drag a half-naked ChongLy Thao into snow-covered streets for existing, in their eyes, incorrectly; that is, non-whitely. In the name of safety, a one-year-old and her father are pepper-sprayed in the eyes whilst sitting in their car at the wrong time.Dismantling the Oppressor to Dismantle OppressionFor all the state’s claims that a “war on crime” is being waged, it has always been and remains a war against our bodies, the means with which they wish to realize ICE’s utopic “Amazon Prime for human beings.” Similarly, the War on Drugs only ever served to terrorize our communities, to lock up and exploit our bodies. Meanwhile, this matter of “crime” never dissipated. For centuries, they tell us that it is our fault – our heinous “crimes” – that we are stripped of our families and our dignity. Meanwhile, politicians of all parties and colors have sat idle even while claiming to bear our interests to heart. We forget that they hold their money closer.And, not so unlike the slave catchers recruited and paid out to return runaway slaves to their owners, so, too, it is we who are being recruited and paid out to bind and beat one another, to tease out the “other.” That is, unless we bring ourselves to see ourselves not only in the “other,” but in the ones dragging our tired feet across the pavement, forcing our bodies into further submission, pulling the trigger – all whilst looking us dead in the eye.It was James Baldwin who said, “Everyone you’re looking at is also you. You could be that person. You could be that monster, you could be that cop. And you have to decide, in yourself, not to be.”Whilst the money and military might of the state and the oppressive systems that prop it up are, no doubt, daunting, their power is nevertheless maintained by individual choices made in the service of oppression and possession, as opposed to liberation. However, it is also important to remember that other individual choices are the reason we remain today, more free than before even if that freedom may be incomplete. Thus, just as individual choices have the power to oppress, so, too, individual choices have the power to resist oppression; to hold our people in check; to liberate.Only through our decision to not become the monster we fear do we have any hope of collective liberation."

}

]

}