Digital & Print Membership

Yearly + Receive 8 free printed back issues

$420 Annually

Monthly + Receive 3 free printed back issues

$40 Monthly

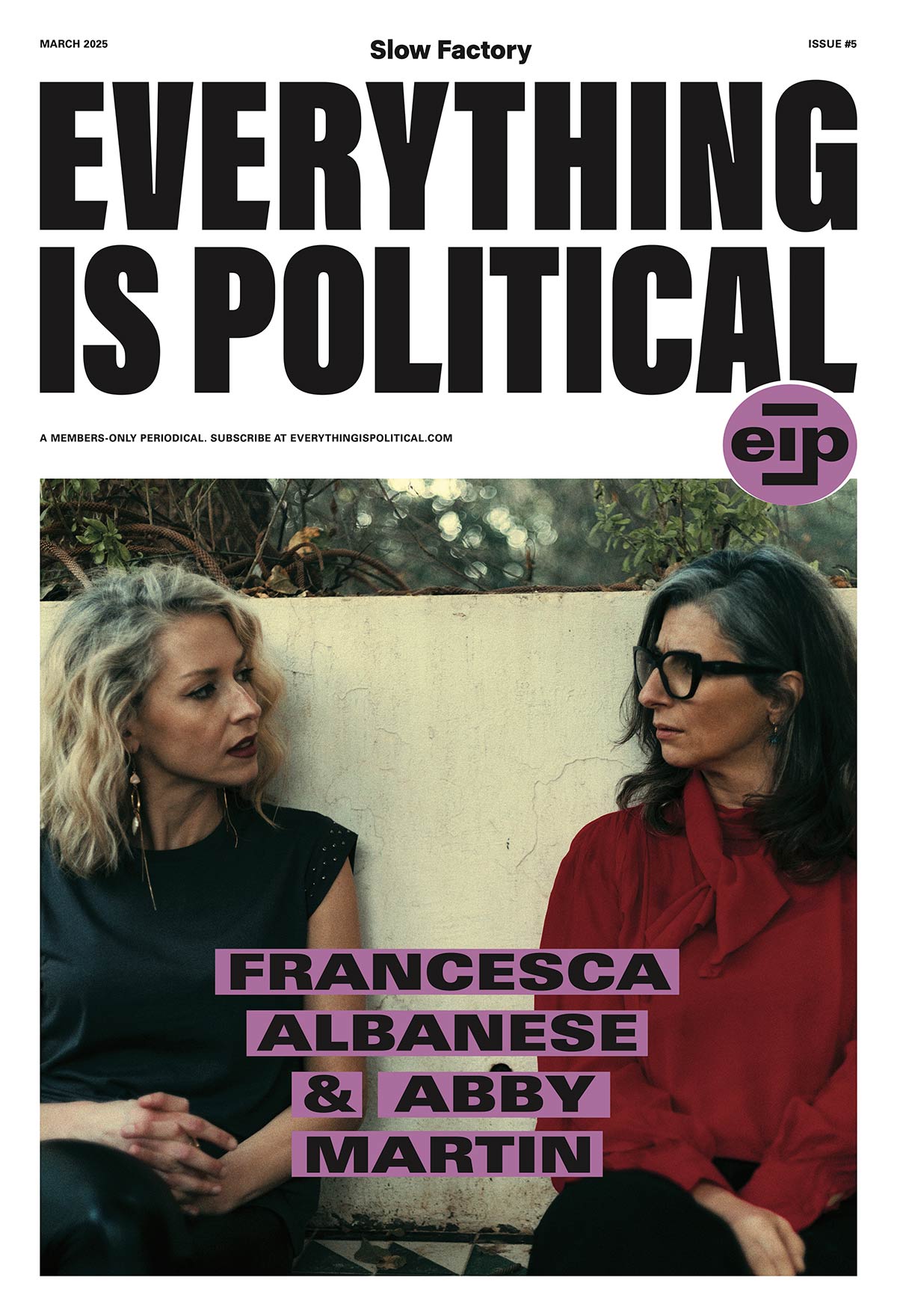

Fatphobia in the Fashion Industry

maya finoh & Jordan Underwood Reflect on Regressive Culture

Reflecting on the cultural shifts we’ve seen since the rise of Ozempic as a blockbuster drug, we are two agency-signed fat models who have been actively working in the fashion industry for years, interviewing each other on the state of plus-size modeling. As models over a US size 22, we have borne the brunt of anti-fatness in the industry over the years and have also experienced the ramifications of cultural body preference shifts on personal and professional levels. Our photo story utilizes both bright colors and more neutral genderqueer aesthetics to shine a spotlight on the outcast beauty that is the fat form which has been increasingly pushed out of public life, despite being depicted as an image of abundance in many cultures historically.

Through interviewing each other, we hope to examine the current move in fashion and culture back to almost Y2K levels of ultra thinness (e.g., the decrease in curve models on the runway, many curve models getting dropped from their agencies, the constant vitriol on social media directed at visibly fat folks, and the declaration that the ‘BBL era’ is over) and how it’s connected to systemic fatphobia stoked by health anxiety and the desire to return to normalcy after years of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The fashion industry is one of the first cultural spheres to manufacture bias against certain body types, facial features, and so on via style trends. Anti- fatness has been and continues to be used as a tool of militarism (as seen through the presidential fitness test, and the Bush Administration’s declaration of a ‘War on Obesity’ in 2002). With authoritarianism rising globally, we posit that publicly naming these regressive trends is the first step as media can be a tool to either perpetuate these systems or disrupt them. Ultimately, we hope this conversation offers readers some possible tools to fight against anti-fat bias in their own lives.

MAYA FINOH: I had a longtime interest in modeling. I would think to myself, “Oh, I would love to model” because I’ve loved fashion since I was a tween. But I don’t think it was until I moved to New York and met a community of creatives—Black, queer, and trans artists especially—that I felt like this dream or this vision of me as a fat Black model in the industry could become a reality. For non-essential workers, the COVID-19 lockdown offered the space to focus on hobbies, creative dreams, and other endeavors that you wouldn’t have time to nurture otherwise. So I was lucky to connect with people who were entering their photography practices at that time, who would say to me “Let’s do a test shoot. I just want to shoot.”

I began to post those photoshoots online and then folks from the Parsons MFA Fashion Design & Society Program reached out to me about a class they had about designing inclusively. I had to go to Parsons consistently for a semester and had the clothes that student designers made fit to my body, which was cool. It was a lovely experience being a plus-size fit model, and from there, I started to get asked to do more modeling gigs. I believe it was in July 2021, that my mother agent found me on Instagram, and I became a signed model from there.

When did you become a model?

JORDAN: I always loved fashion. I was that kid that had little outfit sketches on the back of all my papers, and I always loved getting my picture taken, which is kind of funny, I don’t know, kind of cringe, but people always told me that I was really photogenic, which, maybe is fatphobic. I don’t know. “Pretty face” syndrome. That’s neither here nor there. I was always fat, and growing up during the “thin is in” era of the 2000’s, I didn’t really see modeling as a possibility for me. When I moved to New York in 2014, I briefly looked into modeling agencies that had plus size talent on their rosters, but at that time, it was incredibly rare to see a model under 5’7” signed, and I’m 5’4”. So, I tabled that idea.

After graduating in 2018, I was focused primarily on my career as an actor but started doing some modeling on the side. In November 2018, my agent posted a casting call looking for models with no size or height requirements. A friend sent it to me, and I submitted a few headshots and a video of me dancing on a whim, not thinking that anything would come from it. I signed with them that same week, and I’m still with that agency today. That was a huge turning point for me.

When the pandemic hit, theatres closed and I had to shift gears. I had more free time, so I started creating content online. That really helped boost my modeling career. Many of my test shoots and content I was creating on my own were getting shared, and I was able to make connections with brands through social media. Now, my career is about 50/50—half through my agent, half through social media. For plus-size models, especially those of us above a size 20, social media can be crucial because big brands often aren’t looking for models like us.

I find it interesting how the fashion industry seems to want to be bold and innovative and critique oppressive systems, while also so often supporting and reinforcing white supremacist hegemony with their artistic and casting choices. — Jordan

MAYA: You know, I love that you took a chance and applied to that agency just to see what would happen. Within a week, you were signed, and now here we are. I want to focus on the “thin-is-in” era, the Y2K fatphobic era 20 years ago. It’s wild to think about how much fatphobia was normalized. You could be a size eight or whatever, like Jessica Simpson or Raven-Symoné, and be considered the fattest thing in the world. And now we’re regressing back to that. What about this particular socio-political moment makes you think—or rather, makes you know—we’re regressing?

JORDAN: That’s so funny, because I had a very similar question for you: Do you see any differences between the “thin-is-in” fads of history and the current moment we’re in with the rise of Ozempic as a blockbuster drug?

I feel like we asked kind of the same question. For me, now everything is so steeped in neoliberal feminism. You see things like the Hims & Hers ad that was aired during the Superbowl this year. There is an explicit co-option of the language of fat liberation. The language of, specifically, Black radical thinkers has been misappropriated to sell weight loss products, and push anti- fat ideology. These companies slap this language of liberation on top of the same anti-fat rhetoric we’ve witnessed for decades in an attempt to trick us into thinking that they are “body positive” and critical of the anti-fatness of the early 2000s, all the while telling us to literally buy into the very system that they are pretending to critique.

MAYA: Absolutely. I feel like what you’re getting at is that neoliberal feminism, more commonly known as choice feminism, is allowing people to say, “It’s my choice to use this drug that’s meant for diabetic bodies for weight loss.” Let’s start there. Fundamentally, Ozempic was made for people who have a chronic illness and they’re now experiencing shortages trying to get it, so there’s a lack of regard for diabetic people and their needs in the use of this drug solely for weight loss. There’s also this delusion within choice feminism, a belief that choices can exist without the input of the superstructure of society around us. These choices don’t happen in silos, or a bubble, completely absent from influences. Our choices are impacted by fatphobia and other systems of oppression whether we like it or not.

JORDAN: I think it’s important to note that these conversations are happening all the time on social media in comment sections, on TikTok and Instagram and Substack, and always have been. I came to fat liberation through Tumblr in the 2010s but in the 2000s these conversations were being had on LiveJournal and in zines and at places like the NOLOSE conferences. I recently read an article where someone said, and I’m paraphrasing, “The difference between the 2000s thin-is-in moment, and now is that now we’re having these conversations.”

The reality is that people have always been having these conversations, and I think that it’s really disingenuous, or rather, when people say that I find that they are shining a light on their own ignorance to the history of fat liberation and liberation movements in general. Because these conversations have been happening literally forever. Even when talking about the history of body positivity and fat liberation, we go back to the civil rights movement where, many fat Black women who were leaders in that time were talking about anti- fatness as oppressive system that exists under white supremacy. I’m thinking specifically about people like Audre Lorde, Fannie Lou Hamer, and Johnnie Tilmon.

MAYA: Yeah, I always go back to Hunter Shackelford’s definition of fat liberation and how we can’t untie it from anti-Blackness. So in that regard, fat liberation started in the cargo hold of the slave ship. The first acts of rebellion towards fat liberation were the acts of insurrection and rioting that enslaved Africans did on the slave ship. So I absolutely agree.

JORDAN: I see a lot of people, at least when talking about Ozempic, be it via the Hims & Hers commercial or anywhere else that this conversation pops up, I often do see a lot of defensiveness from people, specifically people who have diabetes, bring up the original intended use of the drugs. I see a lot of people who take Ozempic or semaglutides, whatever the mode is, get very dug into the pathology of fatness, saying, “Oh, well, you don’t know what it’s like to be ‘obese’ and have the disease.” I’ve always found that self pathologization really interesting. They are pathologizing their own experiences, obviously, because doctors or whoever have told them to, which is so interesting too, in this current moment, because of the way in which we’ve seen, “obesity” be designated as a disease and then not disease, and the medical community going back and forth. We see flip-flopping from the people who have dedicated their lives to ending fatness as something that exists, period. Medically, and culturally, there seems to be a desire to pathologize fatness, to view being fat as a sickness, but at the same time, we see this consistent critique of a lot of fat activists’ work where people will claim that we’re conflating fatness and disability. So then my question becomes, is fatness a disability? Or is it not?

MAYA: It is. My fatness can be disabling! If I don’t get certain accommodations a place or environment can become inaccessible to me.

JORDAN: And that only seems to be a problem when we say it, and when we ask for accommodations for our disabilities as fat people, whether our disabilities are related to our sizes or not. The people who are the most entrenched in anti-fat ideology really grip to this idea that they are pro-science, but some of the loudest anti-fat voices I’ve encountered online come from people who are not only ignoring the decades of research that we have on the negative health outcomes that fat people face due to weight bias in medicine, but are also coming from people supporting politicians who are blatantly anti-vax and deny climate change.

MAYA: What you’re bringing up makes me think about the difference between the 2000s “thin-is-in” and this 2025 era of regressive body politics, which now has an authoritarian turn, or rather, a new adaptation of a regime in office.

In the Hims & Hers commercial, I found it interesting and Ericka Hart pointed this out, that they used “This is America” by Childish Gambino. I have many critiques of Childish Gambino and that music video, especially its disregard for Black life, but it’s telling that they chose a song meant to critique police brutality and the mass murder of Black people to sell a product related to Ozempic. I think this highlights a major difference between the early 2000s and 2025—a new kind of co-optation, minimization, and disrespect of Black cultural identity.

Black culture is now pop culture in the U.S., and the way we talk about it has changed. In the past year or two, we saw media declaring an end to the ‘BBL era,’ which symbolizes a rejection of bodies that have been stereotyped and associated with Blackness. The Brazilian butt lift, for example, has ties to the eugenics movement of Brazilian plastic surgeons, who aimed to take traits from Indigenous Brazilians and Afro-Brazilians they deemed worthwhile and apply them to lighter-skinned, white Brazilians. So many plastic surgery techniques originating from Brazil were attempts to strip their society of Blackness and Indigeneity while preserving specific “desirable” aspects of those communities.

Many people who claim to be pro-science and anti-vax are still promoting racial pseudoscience about fatness. The hatred of fatness doesn’t come from a concern for health—it’s rooted in racism. — maya

Sabrina Strings, in her book Fearing the Black Body, explains how anti-fatness as a coherent ideology is born out of racism. Fatness was used as a signifier to justify chattel slavery—those Black Africans deemed “fat” were labeled as greedy and lazy, and therefore undeserving of freedom. This marked them as people who deserved to be governed, enslaved, and colonized. The connection between pseudoscience about fatness, white supremacy, and anti-vax ideology has centuries of history aligned with white European hegemony and racial hierarchy.

JORDAN: And it’s admitted pseudoscience, right? Adolphe Quetelet who invented the BMI literally said (paraphrasing), “This is not to be used to determine health. This is for statistics. This is not for medical use.” That man was a proud eugenicist; he was literally a race scientist.

MAYA: Can I circle back to part of our question, about how you think the fashion industry in this particular moment is complicit, aiding and abetting this regression and this increase of fatphobia and all other forms of disregard for bodies that are not white, thin and able-bodied?

JORDAN: When we talk about body politics and body fascism translating into the fashion industry, the industry likes to think of itself as a trendsetter. But I don’t know how much I buy that, especially right now. The fashion industry is almost always a reflection of our politics and culture. That’s not to say there aren’t people in the industry—Black and brown designers, queer and trans designers, disabled designers, fat designers—who are pushing boundaries and making statements through their art and fashion as political commentary. But in this current moment of Ozempic, things have really shifted.

New Year’s 2023, there was a noticeable shift in the industry. I think a lot of us saw it coming, especially given how the conversations around fatness started changing when Ozempic was introduced. A lot of people predicted this moment, including Imani Barbarin, who was creating content back in 2020 warning us about ableism and fatphobia as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

MAYA: I definitely felt that. I think COVID-19, this global pandemic, opened the door to intense anxiety around health. There was also this desire to return to normal after the lockdown, even though the pandemic is still ongoing. But after the end of lockdown, people craved a return to normalcy. It’s also this desire to go back to simpler, more “innocent” times. That translates into wanting ultra-thinness, wanting whiteness. Particularly, there was a push to see healthy and fit bodies after millions of people died and we had to slow down during lockdown. We didn’t want to see sickness or disease. We didn’t want to see disabled people. We wanted to see healthy, fit bodies. So, we became even more anti-fat, and terms like the “R-word” began resurfacing. This moment isn’t just about vitriol; it’s about the desire to dismiss disabled and fat people from public life.

JORDAN: A lot of anti-fatness came into play almost immediately as we saw fatness being blamed for COVID deaths. That is incredibly relevant when we talk about this health anxiety because when you tell people, “Oh, you’re going to die of COVID because you’re fat,” then of course, the cultural response is going to be “Okay. Well, I’m not going to be fat. I’m going to do everything in my power to not be fat so I don’t die and if I get COVID I can be okay.” Even though we know that that’s not how this works, that many thin, “healthy,” able-bodied people have died of COVID and many continue to suffer from the severe effects of long COVID.

MAYA: I would also add that COVID showed a lot of people how the government will abandon you. “If I don’t have health insurance, I better be fit and healthy. I can’t be fat because I can’t trust the state to take care of me.” This reflects the ways in which this country, focused on capitalist accumulation, is willing to sacrifice any human life that gets in the way of profit. I’m not sure how many people fully grasp the totality of it, but I think most folks have a basic understanding of the horrors of our healthcare system right now. Watching so many people drop dead in the early months of the lockdown made it clear: “I can’t be fat or disabled because, literally, the triage protocols are designed to let fat and disabled people die.”

JORDAN: Capitalism is comfortable letting us die, and the solution becomes spending $1,000 a month on a blockbuster drug. Even elevating this drug as a “magic” solution—people call it a magic drug, right? There are claims that it helps curb addiction, alcoholism, and so much more. The list goes on and on. People will tell you semaglutide can solve literally any problem you’re struggling with. And I think people need it to be true, for their sanity, because the reality is not so simple. We want it to be, “Oh, I take this pill or shot, and I’ll be healthy, and I won’t have to struggle.” But that’s just not true. We’ve seen this before—every 10 or 20 years, there’s a new magic drug. It just seems that critical thinking is missing here. We’re not questioning who benefits from this.

I see a lot of people acknowledging the damage of weight stigma while promoting semaglutides as a solution. And I think that’s really interesting because we’re acknowledging a systemic issue and then offering an individual solution for it. Charging people $1,000 a month for this individual solution to a systemic issue. Even if Ozempic were a solution—which it’s not—but following their logic, if they’re presenting it as the answer, Medicaid doesn’t cover Ozempic. Medicaid doesn’t cover any weight loss medication. And we know that people who live in poverty, statistically, are more likely to be fat. So we’re gatekeeping this magic drug from the people most impacted by what they call a disease. They’re saying, “You have a disease, here’s a magic drug to cure you,” but because you’re poor, we’re not going to give it to you. And why is that?

MAYA: Who’s it really for?

JORDAN: Eradicating fatness does not eradicate anti-fatness. And the reality is that fat people have always existed.

MAYA: There’s something I’ve noticed more and more in terms of anti-fat harassment online: “There’s Ozempic now, so there’s no excuse to look like that.” Now Ozempic has become more than what it actually is. It’s become this mythic drug with which you can lose half of your body weight instead of the reality of around 15 to 20 pounds. I think fashion does go hand in hand with our political moment. I’ve been reflecting a lot on Nazi Germany and the collaborators, and how brands like HUGO BOSS, which produced Nazi military uniforms, played a role. It’s interesting seeing figures like Ivanka Trump and Usha Vance dressed in custom couture for the presidential inauguration, especially after the 2016 Trump administration, when many fashion brands made a spectacle of saying they wouldn’t dress or collaborate with them. This election marked a big shift.

I want to talk about this shift, especially how it’s affected us as plus-size models. Since 2020, the introduction of Ozempic as a blockbuster drug, and the end of lockdown, we’ve seen a decrease in opportunities. There’s been a push to get rid of the “COVID-15” and return to normal, which has led to fewer jobs for plus-size models, fewer opportunities on the runway, and even models being dropped from agencies because there are no jobs for them. I’d love to hear your thoughts on this.

JORDAN: I think it’s interesting because, after the start of the lockdown, there was a big push for increased representation of different body sizes. In 2021, it seemed there was more mainstream support for body diversity in commercials and larger companies. Then, it felt like a sharp backlash, as if they pushed too far. This is the trap of representation—when there’s representation without protections, without tangible changes, or without broad-scale education. We see this with transness as well. There’s representation of trans people, but particularly with trans women, this hyper-visibility leads to pushback through transmisogyny, especially for Black trans women, who are exposed to really serious violence.

MAYA: What you’re making me think about is that the uprisings of 2020, particularly the George Floyd and Breonna Taylor protests, that led to that brief moment of increased visibility. Black liberation, both in the U.S. and globally, opened the door for other movements to have space and gain attention. In this case, we’re talking about the performance of representation, but I think it still matters. The increased body diversity in 2020-2021, with more fat, disabled, trans, and darker-skinned models, is rooted in the work of the Black Freedom Struggle Black liberation is key to collective liberation and cannot be downplayed. As we already mentioned, anti-fatness is tied to anti-Blackness, so it makes sense that fat models also had that brief moment, as we saw brands perform their “diversity” with black squares and weak gestures. Ultimately, we know that despite creating diversity and inclusion roles and work plans, these changes have been rolled back in the past year. But the foundation of that brief moment is rooted in Black liberation.

JORDAN: Something that I have always found really frustrating in fat liberation spaces is the whitewashing of fat liberation through the mainstreaming of body positivity, where it’s seen as a cis white lady thing. When you actually engage with fat liberation work, it has always had its roots in Black liberation and the people who are producing the most pivotal texts in fat studies are fat Black queer people like Da’Shaun L. Harrison, Roxanne Gay, Kiese Laymon…

MAYA: It’s like the liberal dilution of that work.

JORDAN: That hyper-focus on representation leaves fat people vulnerable, because people don’t fully understand what they’re fighting for or against. We often name random fat influencers as our leaders, but they’re not equipped for this work. They’re not activists, nor have they studied liberation, especially fat liberation. It’s interesting who gets labeled as activists in this field. People, not necessarily you or I, allow ourselves to be continually let down by those who aren’t qualified. Just because someone has a million followers and is fat doesn’t mean they can tell you how to love yourself. “Tell me how to love myself” will never liberate you. It might give you tools to self-advocate, but it’s not the solution.

MAYA: It’s not about love. Institutions can’t love us. This is about systemic anti-fatness, it’s about whether we can live with dignity or have our lives cut short by others’ fat discrimination and neglect. I also want to uplift Andrea Shaw Nevins, who wrote The Embodiment of Disobedience. She doesn’t get enough credit for naming fat Black women’s contributions to the politics of fat liberation, almost 20 years ago.

We should also touch on anti-fatness in relation to militarism and imperialism, especially in this time of ongoing genocides. I want to bring up a Jerusalem Post article from October 2023 that discussed using the “stress from the Israel-Hamas war to lose weight.” I also want to address how the war on obesity, declared by the Bush administration in 2002 before the Iraq War, framed obesity as a bigger threat than terrorism in the United States. The U.S. Surgeon General Richard Carmona even called obesity “the terror within.”

JORDAN: The war on terror, the war on drugs, the war on obesity, all of these quasi ‘wars’ are waged by the US government to keep us distracted, fighting each other so we don’t fight them. You’re telling me that while we’re witnessing multiple genocides the thing that we should be most focused on is keeping our bodies snatched?

MAYA: Meanwhile, people are starving a couple of miles away from you—being decimated— in fact.

JORDAN: I also think that there’s something in the government wanting the people to be comfortable starving: to keep people weak, to keep people in line, and to say “Don’t eat. It’s better for you.”

MAYA: The declaration of a ‘war on obesity’ frames fatness as an emergency because we need people to be fit—to be police officers or part of the military. The United States requires a steady supply of recruits for the military-industrial complex, which needs soldiers to keep the war machine running.

JORDAN: There is a billboard that I’ve seen many times in my life for bariatric surgery, where it is a before and after, and the before is just some fat guy, and the after, he’s in a fucking police uniform. They said the quiet part out loud: “Be skinny. Arm the state.” When we talk about Israel specifically, that’s also a country that has mandatory military service.

MAYA: Even the way Israelis talk about their military—claiming to have a bunch of vegans—reflects a focus on health and beauty. Discussions about their military might, particularly through the violence they enact on Palestinians through occupation, are bolstered by conversations about Israelis’ perceived health and beauty. The emphasis on “sexiness” and the popularity of white supremacist and fatphobic views on media platforms today support the maintenance of empire. Fatphobia, as an ideology, is a part of the upkeep of empire.

JORDAN: It’s common to see declarations of allegiance to white supremacy followed by hatred of fat people. Most recently, Kanye West’s tweets began with “I am a Nazi” and ended with “I hate fat woke bitches.” Even outside of Kanye, there’s an influencer who posted on TikTok saying, “I hate liberals, love Trump, and hate fat people.” Hatred of fatness is often central to these declarations.

MAYA: I would argue that fatphobia, anti-fatness, and ableism are symptoms of fascist, authoritarian ideologies, which are now consolidating in places like the White House and across Europe. Many nations are experiencing a new fascist turn. Fat and disabled communities serve as universal scapegoats, with people across the political spectrum—whether fascist or leftist—claiming they have no place in the revolution.

JORDAN: I see this often when discussing disability and fatness, where even people in the disability community say, “You did it to yourself,” implying no right to complain. For many, including me, disability and fatness are intertwined; my disability causes weight gain, and for many fat disabled people, inaccessibility stems from fatness, not just separate disabilities. Capitalism shifts the blame onto individuals instead of addressing the systems that keep us sick.

What does it mean to push back when culture has regressed in the way that it has, but also regressed and got smarter? When we’re seeing a sort of blatant co-option of the language of fat liberation, the language of liberation in general, I think we have to go back to the basics. We have to go back to education. We have to go back to having these conversations with people on a one- to-one level and meeting people where they are.

MAYA: To be frank, the pendulum has swung this way, and in 10 years we might see a swing back towards liberal diversity, or rather the liberal politics of representation and diversity with the next wave of movement organizing that happens in U.S. empire. I think then we’ll see a lot of the fashion industry, who at this moment are being outwardly fatphobic, pretend like they weren’t. There’s going to be a lot of revisionism.

There’s always going to be fat people here. Fat people have made it through multiple eras of regressive body politics. Fat people have been here and always will be because you can feed two people exactly the same way, and just because of different genetics and the diverse human experience, they will carry weight in different parts of their body. They’re not going to look the same. It’s the beauty of humanity, and fascism really tries to pretend like that’s not true: that we can get uniformity, we can get Nazi ‘Aryan’ beauty. As fucked up as that regime was—as horrific and unimaginable as the loss of life was—ultimately, this type of thinking does not work. You’ll never be able to eradicate fat and disabled people out of existence.

JORDAN: Obviously it’s so cliche, and everyone is saying it, but community really is key. We have each other. I’m not a pessimist, but fat people saw it coming. If I had a message for thin people, it would be to listen to fat people, listen to fat, Black, and disabled people specifically. This cultural moment should not have been a surprise to anyone, because it was not a surprise to us.

MAYA: Global pandemics have always led to increased ableism, fatphobia, and regressive body politics as people try to regain control after mass loss of life and widespread disability. This pandemic, in particular, has left millions with long COVID and new chronic disabilities, forced to create a new way of life that many are unprepared for. Instead of accommodations or a world that values disability justice, there’s been a move by the ruling class towards fear and control, with a push to return to normal by scapegoating fat and disabled people.

Like you said, it’s crucial to listen to those who’ve studied history and the work of long-time organizers. History doesn’t repeat itself, but it’s shaped by past choices. This articulation of authoritarianism and regressivism demonstrates that.

{

"article":

{

"title" : "Fatphobia in the Fashion Industry: maya finoh & Jordan Underwood Reflect on Regressive Culture",

"author" : "maya finoh, Jordan Underwood",

"category" : "interviews",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/fatphobia-in-the-fashion-industry",

"date" : "2025-03-21 17:36:00 -0400",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/05.jpg",

"excerpt" : "",

"content" : "Reflecting on the cultural shifts we’ve seen since the rise of Ozempic as a blockbuster drug, we are two agency-signed fat models who have been actively working in the fashion industry for years, interviewing each other on the state of plus-size modeling. As models over a US size 22, we have borne the brunt of anti-fatness in the industry over the years and have also experienced the ramifications of cultural body preference shifts on personal and professional levels. Our photo story utilizes both bright colors and more neutral genderqueer aesthetics to shine a spotlight on the outcast beauty that is the fat form which has been increasingly pushed out of public life, despite being depicted as an image of abundance in many cultures historically.Through interviewing each other, we hope to examine the current move in fashion and culture back to almost Y2K levels of ultra thinness (e.g., the decrease in curve models on the runway, many curve models getting dropped from their agencies, the constant vitriol on social media directed at visibly fat folks, and the declaration that the ‘BBL era’ is over) and how it’s connected to systemic fatphobia stoked by health anxiety and the desire to return to normalcy after years of the COVID-19 pandemic.The fashion industry is one of the first cultural spheres to manufacture bias against certain body types, facial features, and so on via style trends. Anti- fatness has been and continues to be used as a tool of militarism (as seen through the presidential fitness test, and the Bush Administration’s declaration of a ‘War on Obesity’ in 2002). With authoritarianism rising globally, we posit that publicly naming these regressive trends is the first step as media can be a tool to either perpetuate these systems or disrupt them. Ultimately, we hope this conversation offers readers some possible tools to fight against anti-fat bias in their own lives.MAYA FINOH: I had a longtime interest in modeling. I would think to myself, “Oh, I would love to model” because I’ve loved fashion since I was a tween. But I don’t think it was until I moved to New York and met a community of creatives—Black, queer, and trans artists especially—that I felt like this dream or this vision of me as a fat Black model in the industry could become a reality. For non-essential workers, the COVID-19 lockdown offered the space to focus on hobbies, creative dreams, and other endeavors that you wouldn’t have time to nurture otherwise. So I was lucky to connect with people who were entering their photography practices at that time, who would say to me “Let’s do a test shoot. I just want to shoot.”I began to post those photoshoots online and then folks from the Parsons MFA Fashion Design & Society Program reached out to me about a class they had about designing inclusively. I had to go to Parsons consistently for a semester and had the clothes that student designers made fit to my body, which was cool. It was a lovely experience being a plus-size fit model, and from there, I started to get asked to do more modeling gigs. I believe it was in July 2021, that my mother agent found me on Instagram, and I became a signed model from there.When did you become a model?JORDAN: I always loved fashion. I was that kid that had little outfit sketches on the back of all my papers, and I always loved getting my picture taken, which is kind of funny, I don’t know, kind of cringe, but people always told me that I was really photogenic, which, maybe is fatphobic. I don’t know. “Pretty face” syndrome. That’s neither here nor there. I was always fat, and growing up during the “thin is in” era of the 2000’s, I didn’t really see modeling as a possibility for me. When I moved to New York in 2014, I briefly looked into modeling agencies that had plus size talent on their rosters, but at that time, it was incredibly rare to see a model under 5’7” signed, and I’m 5’4”. So, I tabled that idea.After graduating in 2018, I was focused primarily on my career as an actor but started doing some modeling on the side. In November 2018, my agent posted a casting call looking for models with no size or height requirements. A friend sent it to me, and I submitted a few headshots and a video of me dancing on a whim, not thinking that anything would come from it. I signed with them that same week, and I’m still with that agency today. That was a huge turning point for me.When the pandemic hit, theatres closed and I had to shift gears. I had more free time, so I started creating content online. That really helped boost my modeling career. Many of my test shoots and content I was creating on my own were getting shared, and I was able to make connections with brands through social media. Now, my career is about 50/50—half through my agent, half through social media. For plus-size models, especially those of us above a size 20, social media can be crucial because big brands often aren’t looking for models like us. I find it interesting how the fashion industry seems to want to be bold and innovative and critique oppressive systems, while also so often supporting and reinforcing white supremacist hegemony with their artistic and casting choices. — JordanMAYA: You know, I love that you took a chance and applied to that agency just to see what would happen. Within a week, you were signed, and now here we are. I want to focus on the “thin-is-in” era, the Y2K fatphobic era 20 years ago. It’s wild to think about how much fatphobia was normalized. You could be a size eight or whatever, like Jessica Simpson or Raven-Symoné, and be considered the fattest thing in the world. And now we’re regressing back to that. What about this particular socio-political moment makes you think—or rather, makes you know—we’re regressing?JORDAN: That’s so funny, because I had a very similar question for you: Do you see any differences between the “thin-is-in” fads of history and the current moment we’re in with the rise of Ozempic as a blockbuster drug?I feel like we asked kind of the same question. For me, now everything is so steeped in neoliberal feminism. You see things like the Hims & Hers ad that was aired during the Superbowl this year. There is an explicit co-option of the language of fat liberation. The language of, specifically, Black radical thinkers has been misappropriated to sell weight loss products, and push anti- fat ideology. These companies slap this language of liberation on top of the same anti-fat rhetoric we’ve witnessed for decades in an attempt to trick us into thinking that they are “body positive” and critical of the anti-fatness of the early 2000s, all the while telling us to literally buy into the very system that they are pretending to critique.MAYA: Absolutely. I feel like what you’re getting at is that neoliberal feminism, more commonly known as choice feminism, is allowing people to say, “It’s my choice to use this drug that’s meant for diabetic bodies for weight loss.” Let’s start there. Fundamentally, Ozempic was made for people who have a chronic illness and they’re now experiencing shortages trying to get it, so there’s a lack of regard for diabetic people and their needs in the use of this drug solely for weight loss. There’s also this delusion within choice feminism, a belief that choices can exist without the input of the superstructure of society around us. These choices don’t happen in silos, or a bubble, completely absent from influences. Our choices are impacted by fatphobia and other systems of oppression whether we like it or not.JORDAN: I think it’s important to note that these conversations are happening all the time on social media in comment sections, on TikTok and Instagram and Substack, and always have been. I came to fat liberation through Tumblr in the 2010s but in the 2000s these conversations were being had on LiveJournal and in zines and at places like the NOLOSE conferences. I recently read an article where someone said, and I’m paraphrasing, “The difference between the 2000s thin-is-in moment, and now is that now we’re having these conversations.”The reality is that people have always been having these conversations, and I think that it’s really disingenuous, or rather, when people say that I find that they are shining a light on their own ignorance to the history of fat liberation and liberation movements in general. Because these conversations have been happening literally forever. Even when talking about the history of body positivity and fat liberation, we go back to the civil rights movement where, many fat Black women who were leaders in that time were talking about anti- fatness as oppressive system that exists under white supremacy. I’m thinking specifically about people like Audre Lorde, Fannie Lou Hamer, and Johnnie Tilmon.MAYA: Yeah, I always go back to Hunter Shackelford’s definition of fat liberation and how we can’t untie it from anti-Blackness. So in that regard, fat liberation started in the cargo hold of the slave ship. The first acts of rebellion towards fat liberation were the acts of insurrection and rioting that enslaved Africans did on the slave ship. So I absolutely agree.JORDAN: I see a lot of people, at least when talking about Ozempic, be it via the Hims & Hers commercial or anywhere else that this conversation pops up, I often do see a lot of defensiveness from people, specifically people who have diabetes, bring up the original intended use of the drugs. I see a lot of people who take Ozempic or semaglutides, whatever the mode is, get very dug into the pathology of fatness, saying, “Oh, well, you don’t know what it’s like to be ‘obese’ and have the disease.” I’ve always found that self pathologization really interesting. They are pathologizing their own experiences, obviously, because doctors or whoever have told them to, which is so interesting too, in this current moment, because of the way in which we’ve seen, “obesity” be designated as a disease and then not disease, and the medical community going back and forth. We see flip-flopping from the people who have dedicated their lives to ending fatness as something that exists, period. Medically, and culturally, there seems to be a desire to pathologize fatness, to view being fat as a sickness, but at the same time, we see this consistent critique of a lot of fat activists’ work where people will claim that we’re conflating fatness and disability. So then my question becomes, is fatness a disability? Or is it not?MAYA: It is. My fatness can be disabling! If I don’t get certain accommodations a place or environment can become inaccessible to me.JORDAN: And that only seems to be a problem when we say it, and when we ask for accommodations for our disabilities as fat people, whether our disabilities are related to our sizes or not. The people who are the most entrenched in anti-fat ideology really grip to this idea that they are pro-science, but some of the loudest anti-fat voices I’ve encountered online come from people who are not only ignoring the decades of research that we have on the negative health outcomes that fat people face due to weight bias in medicine, but are also coming from people supporting politicians who are blatantly anti-vax and deny climate change.MAYA: What you’re bringing up makes me think about the difference between the 2000s “thin-is-in” and this 2025 era of regressive body politics, which now has an authoritarian turn, or rather, a new adaptation of a regime in office.In the Hims & Hers commercial, I found it interesting and Ericka Hart pointed this out, that they used “This is America” by Childish Gambino. I have many critiques of Childish Gambino and that music video, especially its disregard for Black life, but it’s telling that they chose a song meant to critique police brutality and the mass murder of Black people to sell a product related to Ozempic. I think this highlights a major difference between the early 2000s and 2025—a new kind of co-optation, minimization, and disrespect of Black cultural identity.Black culture is now pop culture in the U.S., and the way we talk about it has changed. In the past year or two, we saw media declaring an end to the ‘BBL era,’ which symbolizes a rejection of bodies that have been stereotyped and associated with Blackness. The Brazilian butt lift, for example, has ties to the eugenics movement of Brazilian plastic surgeons, who aimed to take traits from Indigenous Brazilians and Afro-Brazilians they deemed worthwhile and apply them to lighter-skinned, white Brazilians. So many plastic surgery techniques originating from Brazil were attempts to strip their society of Blackness and Indigeneity while preserving specific “desirable” aspects of those communities. Many people who claim to be pro-science and anti-vax are still promoting racial pseudoscience about fatness. The hatred of fatness doesn’t come from a concern for health—it’s rooted in racism. — mayaSabrina Strings, in her book Fearing the Black Body, explains how anti-fatness as a coherent ideology is born out of racism. Fatness was used as a signifier to justify chattel slavery—those Black Africans deemed “fat” were labeled as greedy and lazy, and therefore undeserving of freedom. This marked them as people who deserved to be governed, enslaved, and colonized. The connection between pseudoscience about fatness, white supremacy, and anti-vax ideology has centuries of history aligned with white European hegemony and racial hierarchy.JORDAN: And it’s admitted pseudoscience, right? Adolphe Quetelet who invented the BMI literally said (paraphrasing), “This is not to be used to determine health. This is for statistics. This is not for medical use.” That man was a proud eugenicist; he was literally a race scientist.MAYA: Can I circle back to part of our question, about how you think the fashion industry in this particular moment is complicit, aiding and abetting this regression and this increase of fatphobia and all other forms of disregard for bodies that are not white, thin and able-bodied?JORDAN: When we talk about body politics and body fascism translating into the fashion industry, the industry likes to think of itself as a trendsetter. But I don’t know how much I buy that, especially right now. The fashion industry is almost always a reflection of our politics and culture. That’s not to say there aren’t people in the industry—Black and brown designers, queer and trans designers, disabled designers, fat designers—who are pushing boundaries and making statements through their art and fashion as political commentary. But in this current moment of Ozempic, things have really shifted.New Year’s 2023, there was a noticeable shift in the industry. I think a lot of us saw it coming, especially given how the conversations around fatness started changing when Ozempic was introduced. A lot of people predicted this moment, including Imani Barbarin, who was creating content back in 2020 warning us about ableism and fatphobia as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic.MAYA: I definitely felt that. I think COVID-19, this global pandemic, opened the door to intense anxiety around health. There was also this desire to return to normal after the lockdown, even though the pandemic is still ongoing. But after the end of lockdown, people craved a return to normalcy. It’s also this desire to go back to simpler, more “innocent” times. That translates into wanting ultra-thinness, wanting whiteness. Particularly, there was a push to see healthy and fit bodies after millions of people died and we had to slow down during lockdown. We didn’t want to see sickness or disease. We didn’t want to see disabled people. We wanted to see healthy, fit bodies. So, we became even more anti-fat, and terms like the “R-word” began resurfacing. This moment isn’t just about vitriol; it’s about the desire to dismiss disabled and fat people from public life.JORDAN: A lot of anti-fatness came into play almost immediately as we saw fatness being blamed for COVID deaths. That is incredibly relevant when we talk about this health anxiety because when you tell people, “Oh, you’re going to die of COVID because you’re fat,” then of course, the cultural response is going to be “Okay. Well, I’m not going to be fat. I’m going to do everything in my power to not be fat so I don’t die and if I get COVID I can be okay.” Even though we know that that’s not how this works, that many thin, “healthy,” able-bodied people have died of COVID and many continue to suffer from the severe effects of long COVID.MAYA: I would also add that COVID showed a lot of people how the government will abandon you. “If I don’t have health insurance, I better be fit and healthy. I can’t be fat because I can’t trust the state to take care of me.” This reflects the ways in which this country, focused on capitalist accumulation, is willing to sacrifice any human life that gets in the way of profit. I’m not sure how many people fully grasp the totality of it, but I think most folks have a basic understanding of the horrors of our healthcare system right now. Watching so many people drop dead in the early months of the lockdown made it clear: “I can’t be fat or disabled because, literally, the triage protocols are designed to let fat and disabled people die.”JORDAN: Capitalism is comfortable letting us die, and the solution becomes spending $1,000 a month on a blockbuster drug. Even elevating this drug as a “magic” solution—people call it a magic drug, right? There are claims that it helps curb addiction, alcoholism, and so much more. The list goes on and on. People will tell you semaglutide can solve literally any problem you’re struggling with. And I think people need it to be true, for their sanity, because the reality is not so simple. We want it to be, “Oh, I take this pill or shot, and I’ll be healthy, and I won’t have to struggle.” But that’s just not true. We’ve seen this before—every 10 or 20 years, there’s a new magic drug. It just seems that critical thinking is missing here. We’re not questioning who benefits from this.I see a lot of people acknowledging the damage of weight stigma while promoting semaglutides as a solution. And I think that’s really interesting because we’re acknowledging a systemic issue and then offering an individual solution for it. Charging people $1,000 a month for this individual solution to a systemic issue. Even if Ozempic were a solution—which it’s not—but following their logic, if they’re presenting it as the answer, Medicaid doesn’t cover Ozempic. Medicaid doesn’t cover any weight loss medication. And we know that people who live in poverty, statistically, are more likely to be fat. So we’re gatekeeping this magic drug from the people most impacted by what they call a disease. They’re saying, “You have a disease, here’s a magic drug to cure you,” but because you’re poor, we’re not going to give it to you. And why is that?MAYA: Who’s it really for?JORDAN: Eradicating fatness does not eradicate anti-fatness. And the reality is that fat people have always existed.MAYA: There’s something I’ve noticed more and more in terms of anti-fat harassment online: “There’s Ozempic now, so there’s no excuse to look like that.” Now Ozempic has become more than what it actually is. It’s become this mythic drug with which you can lose half of your body weight instead of the reality of around 15 to 20 pounds. I think fashion does go hand in hand with our political moment. I’ve been reflecting a lot on Nazi Germany and the collaborators, and how brands like HUGO BOSS, which produced Nazi military uniforms, played a role. It’s interesting seeing figures like Ivanka Trump and Usha Vance dressed in custom couture for the presidential inauguration, especially after the 2016 Trump administration, when many fashion brands made a spectacle of saying they wouldn’t dress or collaborate with them. This election marked a big shift.I want to talk about this shift, especially how it’s affected us as plus-size models. Since 2020, the introduction of Ozempic as a blockbuster drug, and the end of lockdown, we’ve seen a decrease in opportunities. There’s been a push to get rid of the “COVID-15” and return to normal, which has led to fewer jobs for plus-size models, fewer opportunities on the runway, and even models being dropped from agencies because there are no jobs for them. I’d love to hear your thoughts on this.JORDAN: I think it’s interesting because, after the start of the lockdown, there was a big push for increased representation of different body sizes. In 2021, it seemed there was more mainstream support for body diversity in commercials and larger companies. Then, it felt like a sharp backlash, as if they pushed too far. This is the trap of representation—when there’s representation without protections, without tangible changes, or without broad-scale education. We see this with transness as well. There’s representation of trans people, but particularly with trans women, this hyper-visibility leads to pushback through transmisogyny, especially for Black trans women, who are exposed to really serious violence.MAYA: What you’re making me think about is that the uprisings of 2020, particularly the George Floyd and Breonna Taylor protests, that led to that brief moment of increased visibility. Black liberation, both in the U.S. and globally, opened the door for other movements to have space and gain attention. In this case, we’re talking about the performance of representation, but I think it still matters. The increased body diversity in 2020-2021, with more fat, disabled, trans, and darker-skinned models, is rooted in the work of the Black Freedom Struggle Black liberation is key to collective liberation and cannot be downplayed. As we already mentioned, anti-fatness is tied to anti-Blackness, so it makes sense that fat models also had that brief moment, as we saw brands perform their “diversity” with black squares and weak gestures. Ultimately, we know that despite creating diversity and inclusion roles and work plans, these changes have been rolled back in the past year. But the foundation of that brief moment is rooted in Black liberation.JORDAN: Something that I have always found really frustrating in fat liberation spaces is the whitewashing of fat liberation through the mainstreaming of body positivity, where it’s seen as a cis white lady thing. When you actually engage with fat liberation work, it has always had its roots in Black liberation and the people who are producing the most pivotal texts in fat studies are fat Black queer people like Da’Shaun L. Harrison, Roxanne Gay, Kiese Laymon…MAYA: It’s like the liberal dilution of that work.JORDAN: That hyper-focus on representation leaves fat people vulnerable, because people don’t fully understand what they’re fighting for or against. We often name random fat influencers as our leaders, but they’re not equipped for this work. They’re not activists, nor have they studied liberation, especially fat liberation. It’s interesting who gets labeled as activists in this field. People, not necessarily you or I, allow ourselves to be continually let down by those who aren’t qualified. Just because someone has a million followers and is fat doesn’t mean they can tell you how to love yourself. “Tell me how to love myself” will never liberate you. It might give you tools to self-advocate, but it’s not the solution.MAYA: It’s not about love. Institutions can’t love us. This is about systemic anti-fatness, it’s about whether we can live with dignity or have our lives cut short by others’ fat discrimination and neglect. I also want to uplift Andrea Shaw Nevins, who wrote The Embodiment of Disobedience. She doesn’t get enough credit for naming fat Black women’s contributions to the politics of fat liberation, almost 20 years ago.We should also touch on anti-fatness in relation to militarism and imperialism, especially in this time of ongoing genocides. I want to bring up a Jerusalem Post article from October 2023 that discussed using the “stress from the Israel-Hamas war to lose weight.” I also want to address how the war on obesity, declared by the Bush administration in 2002 before the Iraq War, framed obesity as a bigger threat than terrorism in the United States. The U.S. Surgeon General Richard Carmona even called obesity “the terror within.”JORDAN: The war on terror, the war on drugs, the war on obesity, all of these quasi ‘wars’ are waged by the US government to keep us distracted, fighting each other so we don’t fight them. You’re telling me that while we’re witnessing multiple genocides the thing that we should be most focused on is keeping our bodies snatched?MAYA: Meanwhile, people are starving a couple of miles away from you—being decimated— in fact.JORDAN: I also think that there’s something in the government wanting the people to be comfortable starving: to keep people weak, to keep people in line, and to say “Don’t eat. It’s better for you.” MAYA: The declaration of a ‘war on obesity’ frames fatness as an emergency because we need people to be fit—to be police officers or part of the military. The United States requires a steady supply of recruits for the military-industrial complex, which needs soldiers to keep the war machine running.JORDAN: There is a billboard that I’ve seen many times in my life for bariatric surgery, where it is a before and after, and the before is just some fat guy, and the after, he’s in a fucking police uniform. They said the quiet part out loud: “Be skinny. Arm the state.” When we talk about Israel specifically, that’s also a country that has mandatory military service.MAYA: Even the way Israelis talk about their military—claiming to have a bunch of vegans—reflects a focus on health and beauty. Discussions about their military might, particularly through the violence they enact on Palestinians through occupation, are bolstered by conversations about Israelis’ perceived health and beauty. The emphasis on “sexiness” and the popularity of white supremacist and fatphobic views on media platforms today support the maintenance of empire. Fatphobia, as an ideology, is a part of the upkeep of empire.JORDAN: It’s common to see declarations of allegiance to white supremacy followed by hatred of fat people. Most recently, Kanye West’s tweets began with “I am a Nazi” and ended with “I hate fat woke bitches.” Even outside of Kanye, there’s an influencer who posted on TikTok saying, “I hate liberals, love Trump, and hate fat people.” Hatred of fatness is often central to these declarations. MAYA: I would argue that fatphobia, anti-fatness, and ableism are symptoms of fascist, authoritarian ideologies, which are now consolidating in places like the White House and across Europe. Many nations are experiencing a new fascist turn. Fat and disabled communities serve as universal scapegoats, with people across the political spectrum—whether fascist or leftist—claiming they have no place in the revolution.JORDAN: I see this often when discussing disability and fatness, where even people in the disability community say, “You did it to yourself,” implying no right to complain. For many, including me, disability and fatness are intertwined; my disability causes weight gain, and for many fat disabled people, inaccessibility stems from fatness, not just separate disabilities. Capitalism shifts the blame onto individuals instead of addressing the systems that keep us sick.What does it mean to push back when culture has regressed in the way that it has, but also regressed and got smarter? When we’re seeing a sort of blatant co-option of the language of fat liberation, the language of liberation in general, I think we have to go back to the basics. We have to go back to education. We have to go back to having these conversations with people on a one- to-one level and meeting people where they are.MAYA: To be frank, the pendulum has swung this way, and in 10 years we might see a swing back towards liberal diversity, or rather the liberal politics of representation and diversity with the next wave of movement organizing that happens in U.S. empire. I think then we’ll see a lot of the fashion industry, who at this moment are being outwardly fatphobic, pretend like they weren’t. There’s going to be a lot of revisionism.There’s always going to be fat people here. Fat people have made it through multiple eras of regressive body politics. Fat people have been here and always will be because you can feed two people exactly the same way, and just because of different genetics and the diverse human experience, they will carry weight in different parts of their body. They’re not going to look the same. It’s the beauty of humanity, and fascism really tries to pretend like that’s not true: that we can get uniformity, we can get Nazi ‘Aryan’ beauty. As fucked up as that regime was—as horrific and unimaginable as the loss of life was—ultimately, this type of thinking does not work. You’ll never be able to eradicate fat and disabled people out of existence.JORDAN: Obviously it’s so cliche, and everyone is saying it, but community really is key. We have each other. I’m not a pessimist, but fat people saw it coming. If I had a message for thin people, it would be to listen to fat people, listen to fat, Black, and disabled people specifically. This cultural moment should not have been a surprise to anyone, because it was not a surprise to us.MAYA: Global pandemics have always led to increased ableism, fatphobia, and regressive body politics as people try to regain control after mass loss of life and widespread disability. This pandemic, in particular, has left millions with long COVID and new chronic disabilities, forced to create a new way of life that many are unprepared for. Instead of accommodations or a world that values disability justice, there’s been a move by the ruling class towards fear and control, with a push to return to normal by scapegoating fat and disabled people.Like you said, it’s crucial to listen to those who’ve studied history and the work of long-time organizers. History doesn’t repeat itself, but it’s shaped by past choices. This articulation of authoritarianism and regressivism demonstrates that."

}

,

"relatedposts": [

{

"title" : "A Call to Arms",

"author" : "Jeremiah Zaeske",

"category" : "essays",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/a-call-to-arms",

"date" : "2026-02-03 11:17:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/1000013371.jpeg",

"excerpt" : "Birds perch on the gaps in barbed wire",

"content" : "Birds perch on the gaps in barbed wireBeckoning us to join themWater trickles through the obstruction in its path as if it were nonexistentWe have forgotten that we are waterVines weave a tapestry through metalIf trees cannot find a gap in the fence they will squeeze their way through,engulf it,absorb the border within themselvesThis is a call to armsLOVEI want my love to break through glassI want it to uproot the weeds that have grown in my heart as it picks through yoursI want it to burn through every piece of fabric stained with bloodLove was never a pacifistWhere there is evil there will also be two kinds of joyOne that revels in the misery,grinning faces posing with dead bodieswhile others look on in silence growing numbBut love is the joy of resilienceThe joy of knowing we will always need eachother enoughto tear down the walls and reach out our handsin spite of everything, even deathTo grab at the roots of ourselvesand plant flowers in place of the hate that’s been sown,though the stems may have thornsThis love will be the callouses born from fighting our waythrough rough brick and sharp glass edges,but they’ll just make it that much softer when palm meets palmThis love will be the fertilizer for a garden of scar tissue,never again to be buried under earth and thick skinThis love will be the seeds taking rootafter a long cold winter,sprouting from our chests and cracks in the pavementto greet a long-awaited springA NURTURING DEATHShot-gun weddingDrive-by baby showerClose-range baptismBurn down the forest,the church and the steepleThe baby’s gender is Destruction,Death, andPrimordial ChaosWe are unlocking the worlds they shut away,beyond the talons of textbook definitions,worlds they swore could never existworlds they swore to destroyWe’re pulling out fragmentsthrough the cracked open doorto fill the potholes and cracked cementof our bodymindsouls,to make salve for the woundsThe ones they claimed were pre-existingand unfillableand unfixableand “who’s going to pay for that?”We are toppling immovable fortresseslimb by limb,peeling off skin and tearing through tendonto reveal the brittle forgeries of boneWe are de-manufacturing wildernessNot just free reign for the treesor even all the life they hold,but regrowth for the village of Ahwahnee,birds pecking out the eyes of campers at YosemiteWhat remains will be fed back into the ecosystem,into the bellies of bears and mountain lions,swallowed by insects and earthuntil it’s decayed enough to fertilize the soiland grow foodmedicinelifeA rebirthA nurturing death"

}

,

{

"title" : "This is America: Land of the Occupied, Home of the Capitalists",

"author" : "Mattea Mun",

"category" : "essays",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/this-is-america",

"date" : "2026-02-03 11:11:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/ice-protest-2-gty-gmh-260130_1769810312461_hpMain.jpg",

"excerpt" : "They tell us we live in the land of the free. They declare, “we the people,” and we assume they mean us when we were only ever defined – designed – to be the fodder to build their “life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness.”",

"content" : "They tell us we live in the land of the free. They declare, “we the people,” and we assume they mean us when we were only ever defined – designed – to be the fodder to build their “life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness.”On a Thursday, a 2-year-old girl returned home from the store with her father, Elvis Tipan-Echeverria, when unknown, masked agents trespassed onto their driveway and smashed the window in. In the name of defending the pursuit of happiness, she, with her father, was shoved into a car with no car seat and placed on a plane to Texas. This little girl was eventually returned to her mother in Minnesota; her father – still imprisoned in the land of the free.In the name of liberty, 5-year-old Liam Ramos, with his father, was seized and flown away from his mother and his home to sit in a detention facility in Texas, where his education will halt, his freedom is non-existent, and his pursuit of happiness – denied.In the name of life, Chaofeng Ge was “found” hanging, dead, in a shower stall in detention, his death declared a suicide though his hands and feet were bound behind his back, a fact evidently not deemed worthy of being initially disclosed. Geraldo Lunas Campos was handcuffed, tackled and choked – murdered – in detention, in an effort to “save” him. Victor Manuel Diaz, too, was “found” dead, a “presumed suicide,” the autopsy – classified.American voters like to declare that our present reality isn’t “what they voted for,” despite the fact that one of Donald Trump’s campaign promises in the 2024 election was to “carry out the largest domestic deportation operation in American history,” inevitably according to xenophobic and white supremacist lines. What many of us fail to remember is that this is not the first time we have voted for this. Indeed, I am not confident there is any point in American history that we have not collectively voted for this, regardless of so-called “party lines.”We Have Been Here BeforeWhile the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) was founded in 2003, slavery and genocide predated the very Constitution of the United States, the bodies of African Americans and Indigenous Americans brutalized and broken in the service of laying the foundations of (white) American wealth. Though slavery was “abolished” in 1865 by the 13th amendment, this did not end the policing of racialized bodies.During the Reconstruction era, convict leasing and black codes preserved the conditions and social hierarchy that existed under slavery. Moreover, any legal rights afforded Black Americans were and still are persistently undermined by their inferior social caste, whereby their deaths and suffering at the hands of law enforcement, the healthcare system and other Americans often goes unprosecuted and/or unpunished.Within WWII-era Japanese internment camps, inmates were stripped of their freedom to move, subjected to harsh living conditions and coerced to partake in underpaid, unprotected labor.The Lucrative Business of Slavery and its Bipartisan ProfiteersTo this day, the prison system remains a potent vestige of slavery, again for the sake of profit, as inmates’ human rights are systematically liquidated. As early as the 1980s, the federal government has contracted for-profit prison corporations to operate federal detention facilities. Today, over 90% of ICE detention facilities are operated by for-profit prison corporations as of 2023, a figure which increased from 79% within Biden’s presidency alone.These trends, in conjunction with the ongoing mass detainments of America’s people of color, are not surprising when we consider the immense profits our politicians and some Americans stand to gain, made possible by the continuous enslavement of racialized bodies.Our bodies are their profit.Under the Voluntary Work Program, forced carceral labor is codified, whereby detainees are to receive “monetary compensation of not less than $1.00 per day of work completed,” their “voluntary” labor absolving them of legal employee protections, such as minimum wage. And although ICE affirms that “all detention facilities shall comply with all applicable health and safety regulations and standards,” there is confusion as to how these standards are checked, especially when we consider the Trump administration closed the DHS’s Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties in March 2025.Nevertheless, several lawsuits and detainee testimonies attest to the fact that the work program is rarely voluntary, the survival of themselves and the facilities imprisoning them hinging upon their labor and minimal income. Indeed, many detainees are expected to purchase their own basic products, such as toilet paper and soap. Other detainees recall being threatened with solitary confinement, poorer living conditions and material punishment if they refused to work. Martha Gonzalez was denied access to sanitary pads when she requested a day off work, demonstrative of a larger pattern of ICE’s refusal to provide hygiene products and spaces to maintain one’s hygiene in a dignified manner.In 2023, GEO Group, one of the largest for-profit prison corporations, made over $2.4 billion in revenue, of which ICE, as their largest customer, accounted for 43%, or $1.04 million. ICE also accounted for 30% of CoreCivic’s – another large for-profit prison corporation – revenue. Thus, our bodies enable these companies to amass hundreds of millions in profit.Incidentally, CoreCivic and GEO Group are among the private prison companies that contribute the most to political campaigns, parties and candidates. In the 2024 election cycle, GEO Group gave $3.7 million in contributions, including $1 million to Make America Great Again Inc, while CoreCivic provided roughly $785,000 in contributions. While Republican candidates and committees have been the recipient of the large majority of these funds in recent years, Democrats and the Democratic Party are also guilty of accepting funding from these corporations, among others. In the 2024 cycle, CoreCivic contributed $50,000 to the Democratic Lieutenant Governors Association and Kamala Harris received $9,500 from GEO Group.The opportunities for profit extend even further beyond the U.S.’s borders as more and more nations are gradually entering deals to imprison noncitizen deportees coming from the U.S. In November, $7.5 million was paid out to Equatorial Guinea for this purpose. Alongside other Latin American countries like Costa Rica and El Salvador, Argentina is also rumored to strike their own deal with the U.S.Our bodies are their profit.The ongoing ICE campaign stands as a bipartisan issue, mirroring the ways our country’s deepest social inequalities have been repeatedly upheld on all sides of the political aisle throughout our history.The Occupied Mind and BodyMoreover, the policing of racialized bodies does not merely pertain to the body alone as a site to be moved and removed. Rather, this violence is also waged in our social spaces, in our fears and inside of our bodies.In the classroom, our curriculums hardly, if at all, represent a version of events where we existed and meanwhile the current administration actively tries to erase any part of history we are given a claim to. Such initiatives, too, have been supported for generations, reflected in the 150-year period Indigenous American and Hawaiian children were forcibly taken from their homes and sent to boarding schools designed to facilitate their assimilation and more seamless theft of their native lands.In our social spaces and lives – if not yet brutally taken – liberty and the pursuit of happiness is not ours for the taking. We are perpetually told under what conditions our movement is permissible. Decades of redlining have, in many ways, preserved segregation and pooled the best resources for the white and the wealthy to the detriment of communities of color.But even this is not enough.They police us from the inside, too. In exchange for gifts like food and photographs of her daughter, a Nicaraguan woman was subjected to have sex with a now former ICE officer whilst in detention. A “romantic relationship,” according to federal prosecutors. Our suffering is still romanticized even when guilt has been assigned. What they still do not realize is that there is no place for romance to reside so long as we remain shackled, our bodies – looted.From the inside, they forcibly remove our reproductive organs, then and now. Many of us were among the 70,000 forcibly sterilized in the 20th-century, deemed “unfit” to reproduce. As we speak, 32% of surgeries performed in ICE detention facilities are performed without proper authorization, and there are reports of mass hysterectomies being exacted behind closed doors.They dictate our movements, lock us up, take our insides out, inject their fantasies onto and into our bodies, deprive us of our right to learn and to work and to live. And even if they have not yet come bounding at our doorstep, we lie anxiously in wait for the moment our past may catch up with us and seep, once again, back into our present.And yet, they have the audacity to say that it is by our hands that we are dying; that if only we had lived and loved differently, things wouldn’t be this way. In the name of safety and peace, they force our bodies into hiding or otherwise out onto the streets, despite the fact that only 5% of us have been implicated in a violent crime. In the name of safety, they drag a half-naked ChongLy Thao into snow-covered streets for existing, in their eyes, incorrectly; that is, non-whitely. In the name of safety, a one-year-old and her father are pepper-sprayed in the eyes whilst sitting in their car at the wrong time.Dismantling the Oppressor to Dismantle OppressionFor all the state’s claims that a “war on crime” is being waged, it has always been and remains a war against our bodies, the means with which they wish to realize ICE’s utopic “Amazon Prime for human beings.” Similarly, the War on Drugs only ever served to terrorize our communities, to lock up and exploit our bodies. Meanwhile, this matter of “crime” never dissipated. For centuries, they tell us that it is our fault – our heinous “crimes” – that we are stripped of our families and our dignity. Meanwhile, politicians of all parties and colors have sat idle even while claiming to bear our interests to heart. We forget that they hold their money closer.And, not so unlike the slave catchers recruited and paid out to return runaway slaves to their owners, so, too, it is we who are being recruited and paid out to bind and beat one another, to tease out the “other.” That is, unless we bring ourselves to see ourselves not only in the “other,” but in the ones dragging our tired feet across the pavement, forcing our bodies into further submission, pulling the trigger – all whilst looking us dead in the eye.It was James Baldwin who said, “Everyone you’re looking at is also you. You could be that person. You could be that monster, you could be that cop. And you have to decide, in yourself, not to be.”Whilst the money and military might of the state and the oppressive systems that prop it up are, no doubt, daunting, their power is nevertheless maintained by individual choices made in the service of oppression and possession, as opposed to liberation. However, it is also important to remember that other individual choices are the reason we remain today, more free than before even if that freedom may be incomplete. Thus, just as individual choices have the power to oppress, so, too, individual choices have the power to resist oppression; to hold our people in check; to liberate.Only through our decision to not become the monster we fear do we have any hope of collective liberation."

}

,

{

"title" : "Couture in Paris, Cuts at the 'Post'",

"author" : "Louis Pisano",

"category" : "essay",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/bezos-sanchez-paris-couture-week-wapo-layoffs",

"date" : "2026-02-02 10:49:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/Cover_EIP_Bezos_Sanchez_Pisano.jpg",

"excerpt" : "The Cruel Irony of the Bezos-Sánchez Empire",