Digital & Print Membership

Yearly + Receive 8 free printed back issues

$420 Annually

Monthly + Receive 3 free printed back issues

$40 Monthly

Education Against the End of the World

The Pedagogical Insurgency of Creative Space Beirut

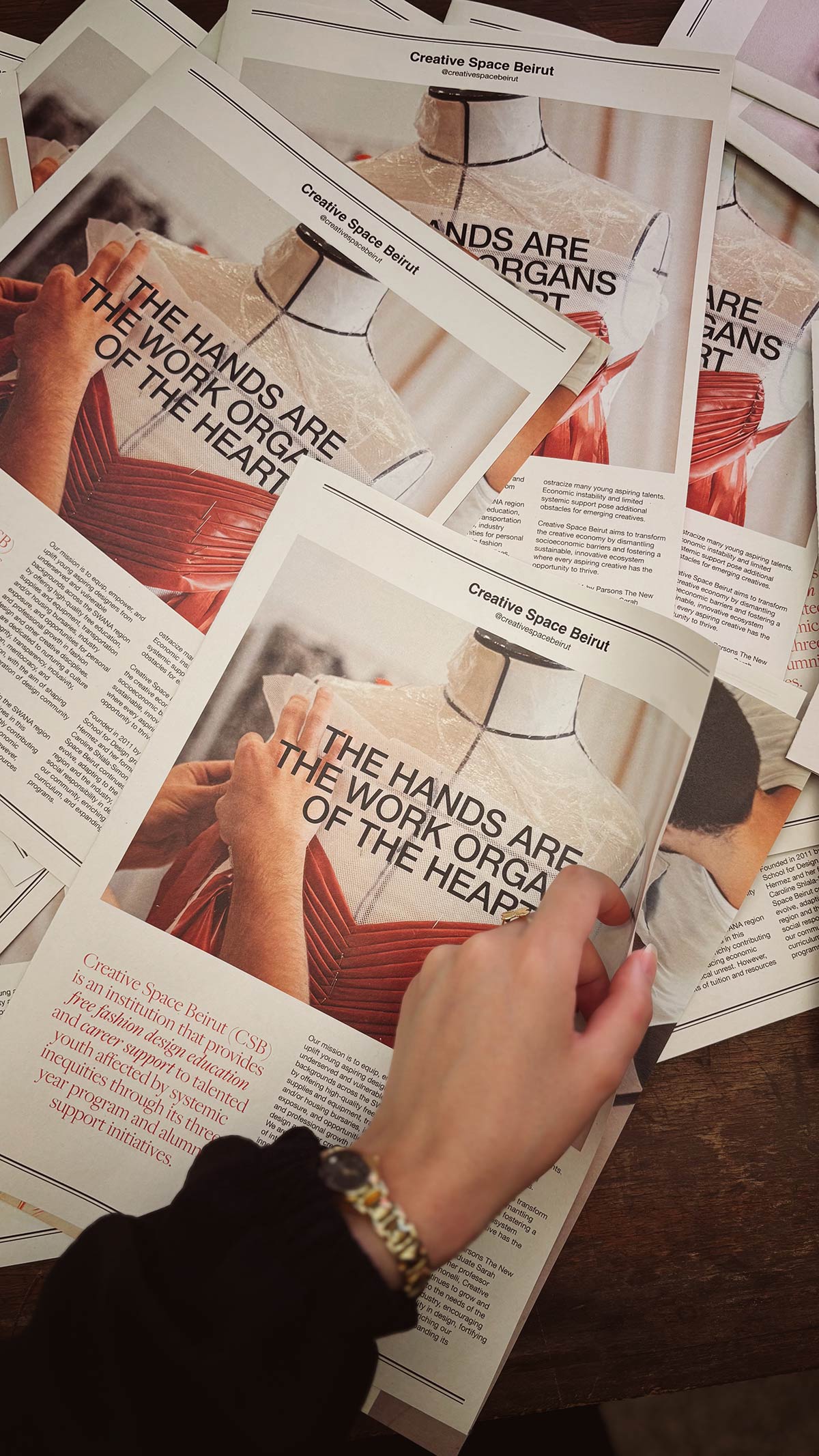

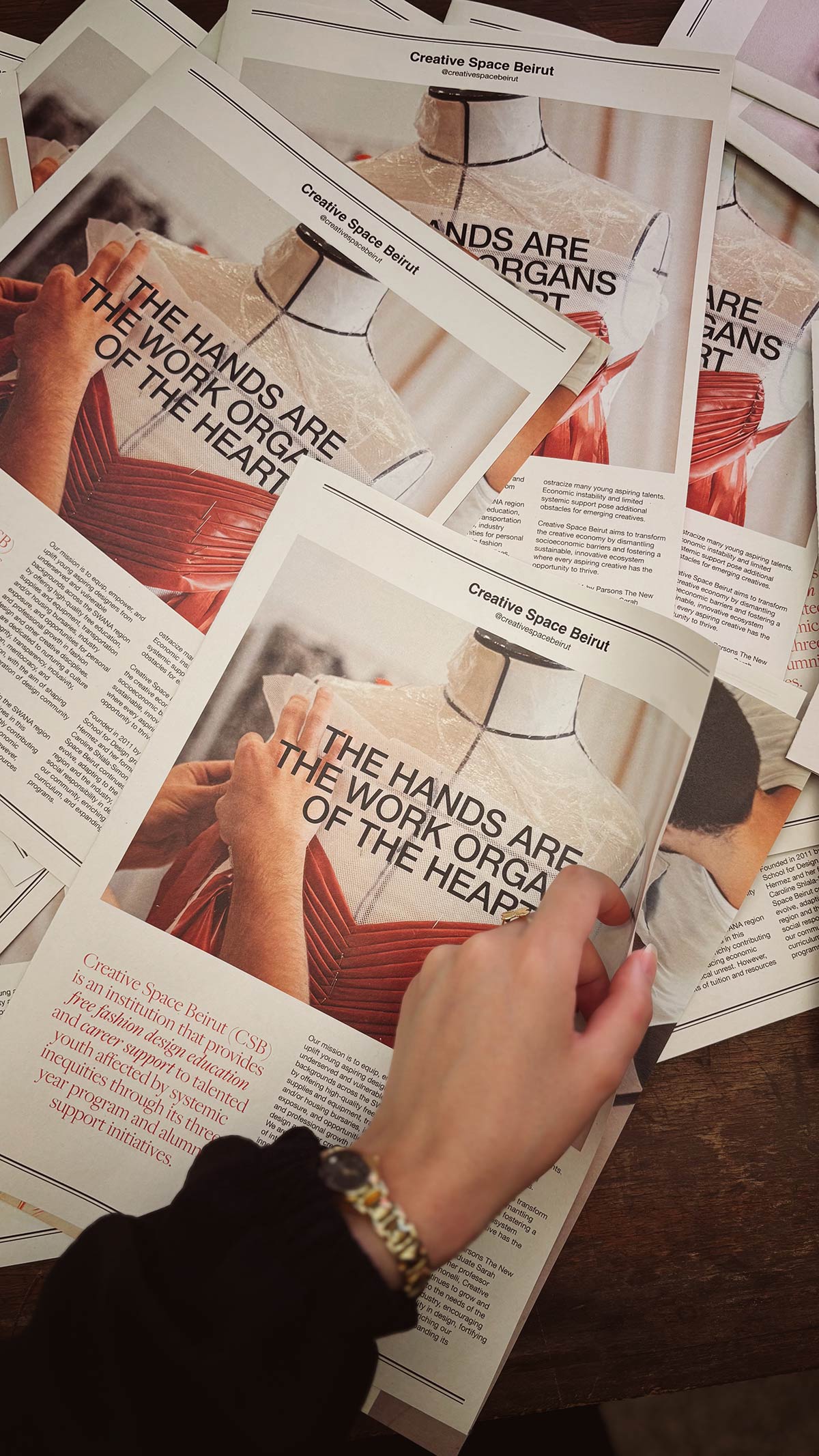

The future feels foreclosed. Late-stage capitalism devours the planet, governments repress more than they protect, and ecological collapse redraws the boundaries of what the coming years might look like. Lebanon has become a microcosm of acceleration— currencies disintegrate, institutions rot, war erases entire neighborhoods. In such a world, to insist on imagining tomorrow becomes an act of defiance. Creative Space Beirut (CSB), a free fashion design school founded in 2011, has built that radical insistence into its very method. On paper, it offers a three-year program in fashion design. In practice, it has become something far rarer: a living model of critical, experiential, and relational pedagogy sustained against the machinery of disintegration.

Fashion education is typically a bastion of privilege—expensive, exclusive, a system that enshrines hierarchies of status and perpetuates a hollow vision of progress built on consumption and extraction. CSB was founded as a refusal of that system. Tuition is abolished; supplies and bursaries for housing and transportation are fully provided. The school deliberately enrolls students who face systemic inequities, young people who would otherwise be shut out of creative industries. They arrive at CSB’s Beirut studio from villages, refugee camps, working-class neighborhoods, and fractured homes, carrying within them the sectarian and social divides of the country. Inside, those divides dissolve into something else. In their place grows solidarity, collective invention, and a radical experiment in access.

The students carry stories of precarity and persistence. Some come from families who question the very validity of pursuing fashion in a place where food, electricity, health, and safety are never guaranteed. Others have endured repression from the state or within their communities, or displacements that would extinguish most ambitions. What binds them together is conviction, the belief that their futures matter, that creativity is not a luxury, but a tool of survival. At CSB, students learn not just to succeed in the industry but to challenge and transform it, building themselves as artists, professionals, and citizens with awareness and responsibility in a fractured world.

The school itself functions like a living body: porous, adaptive, responsive to the shocks of its environment. When the 2020 port explosion reduced its studio to rubble, the body reconstituted itself in the founder’s home until another space could be secured. During the COVID-19 pandemic, it redirected its energy toward the collective, paying students and tailors to produce protective gowns for public hospitals. In wartime, it shifted again, sewing thousands of blankets for displaced families. These were not interruptions but the pulse of its pedagogy: education as survival, adaptation, and defiance. At CSB, resilience is not an abstraction or a tired label, but a daily practice, a pedagogy that refuses paralysis and instead grows new organs and processes in the face of catastrophe.

This is education as liberation. Paulo Freire’s critique of the “banking model” of education casts students as passive vessels to be filled. CSB insists on the opposite: that students’ struggles, imaginations, and histories are the raw material of learning itself. bell hooks called this “engaged pedagogy,” an education rooted in the body, community, and political struggle.

At CSB, these theories take form. Creation becomes survival. Design becomes dissent. Pedagogy becomes politics.

The studio is a crucible of collective practice. Within this environment, students design, cut, drape, and stitch against a backdrop of scarcity, salvaged fabrics, a small number of computers, sputtering generators, and machines that refuse to die. But learning here is not only technical; it is relational and existential. Students collaborate with local artisans, international designers, and industry players, cultivating networks of solidarity rather than competition. This is deliberate. In a country fractured by sectarianism and in a global industry defined by exploitation, CSB wagers that community itself is the curriculum. To learn here is to learn not only how to navigate the industry, but how to make a life with others in a landscape of annihilation.

This ethos crystallized in June 2025 with We Have Arrived, We Are Home, CSB’s first graduate fashion show in seven years. Against all odds, with limited funding and a political climate on the brink, the show seemed to materialize from nothing. In truth, it was carried into being by more than one hundred volunteers: students, creatives, teachers, and friends. It was more than a graduate showcase; it was a demonstration of what a community can assemble when the world demands only survival, a collective act of refusal staged as fashion, proof that creativity and solidarity can conjure abundance from ruin.

Care and relationship form the other axis of CSB’s pedagogy. Relational theories of education, such as Nel Noddings’ ethics of care and Gert Biesta’s concept of education as encounter, emphasize that teaching and learning unfold in relationship, not in abstraction. CSB embodies this principle in both structure and spirit. Inside, diversity becomes a daily, lived practice: students from different sectarian, socioeconomic, and ethnic backgrounds learn side by side in a shared creative environment. That coexistence is not incidental. The encounter with the “other” becomes part of the curriculum. Externally, the school’s partnerships with like-minded industry movers, artists, artisans, humanitarian organizations, and cultural institutions ground education in real networks of collaboration and interdependence. By engaging directly with these ecosystems, students learn negotiation, context, and care as part of their creative process.

This relational ethos extends beyond graduation. Unlike institutions that sever contact once a degree is conferred, CSB maintains a living relationship with its alumni through mentorship, opportunities to teach, shared resources, inclusion in the CSB Boutique, and ongoing collaborations. The result is a cyclical ecosystem where learning and teaching blur, and where each generation sustains the next. The impact of this model is evident in the trajectories of its graduates: alumni who have worked with renowned designers, launched independent brands, opened production houses, and taken on teaching roles across Lebanon and beyond. Many continue to give back directly, mentoring younger students, collaborating on projects, and creating access to networks that were once closed to them. At CSB, education does not end; it circulates. Here, creativity and connection are inseparable, each sustaining and amplifying the other.

CSB belongs to a lineage of radical schools. Like Venezuela’s El Sistema, it reframes culture as a weapon of empowerment. Like Black Mountain College in the U.S., it melds art, life, and politics into a single experiment. Yet unlike Black Mountain, which flickered briefly and disappeared, CSB has endured through more than a decade of compounded crises, nurturing a generation of alumni who are reshaping creative industries across the region. They are living proof that access to education, when bound to community and care, can transform not only individual lives but entire cultural landscapes.

And while CSB is deeply rooted in Lebanon, its lessons reach beyond it. Across the world, higher education grows ever more exclusionary, strangled by debt, hollowed out by corporate capture, or priced beyond reach. The creative industries mirror these logics, fortified by the same structures of exclusivity and extraction that define neoliberal economies at large. In this context, CSB offers not a romantic exception but a functioning counter-model: proof that education can be free, that pedagogy can be collective, that culture can exist as a commons. It shows that schools can act not as engines of hierarchy but as living organisms, responsive to their times, resistant to the forces that would otherwise dismantle them.

In this way, CSB speaks across borders. It resonates with communities in Latin America seeking to decolonize knowledge, with student movements in Europe demanding debt abolition, with grassroots schools in Africa reclaiming cultural practices suppressed by colonial legacies. It offers not only a vocabulary but a living practice for educators, artists, and organizers across the world who are asking how learning can be reclaimed as a collective right rather than a privatized asset.

To call CSB a fashion school misses the point. It is a pedagogical insurgency, a living organism that adapts, resists, and regenerates in contexts that would otherwise dictate deprivation. In a world unraveling under capitalism, repression, and collapse, CSB asserts another truth: that futures can still be made, even when everything conspires to erase them.

{

"article":

{

"title" : "Education Against the End of the World: The Pedagogical Insurgency of Creative Space Beirut",

"author" : "Sarah Huneidi",

"category" : "essays",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/creative-space-beirut",

"date" : "2025-11-21 09:01:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/CSB-2nd-Year-September-2024-Jury---Miled-Chahla-4.jpg",

"excerpt" : "",

"content" : "The future feels foreclosed. Late-stage capitalism devours the planet, governments repress more than they protect, and ecological collapse redraws the boundaries of what the coming years might look like. Lebanon has become a microcosm of acceleration— currencies disintegrate, institutions rot, war erases entire neighborhoods. In such a world, to insist on imagining tomorrow becomes an act of defiance. Creative Space Beirut (CSB), a free fashion design school founded in 2011, has built that radical insistence into its very method. On paper, it offers a three-year program in fashion design. In practice, it has become something far rarer: a living model of critical, experiential, and relational pedagogy sustained against the machinery of disintegration.Fashion education is typically a bastion of privilege—expensive, exclusive, a system that enshrines hierarchies of status and perpetuates a hollow vision of progress built on consumption and extraction. CSB was founded as a refusal of that system. Tuition is abolished; supplies and bursaries for housing and transportation are fully provided. The school deliberately enrolls students who face systemic inequities, young people who would otherwise be shut out of creative industries. They arrive at CSB’s Beirut studio from villages, refugee camps, working-class neighborhoods, and fractured homes, carrying within them the sectarian and social divides of the country. Inside, those divides dissolve into something else. In their place grows solidarity, collective invention, and a radical experiment in access.The students carry stories of precarity and persistence. Some come from families who question the very validity of pursuing fashion in a place where food, electricity, health, and safety are never guaranteed. Others have endured repression from the state or within their communities, or displacements that would extinguish most ambitions. What binds them together is conviction, the belief that their futures matter, that creativity is not a luxury, but a tool of survival. At CSB, students learn not just to succeed in the industry but to challenge and transform it, building themselves as artists, professionals, and citizens with awareness and responsibility in a fractured world.The school itself functions like a living body: porous, adaptive, responsive to the shocks of its environment. When the 2020 port explosion reduced its studio to rubble, the body reconstituted itself in the founder’s home until another space could be secured. During the COVID-19 pandemic, it redirected its energy toward the collective, paying students and tailors to produce protective gowns for public hospitals. In wartime, it shifted again, sewing thousands of blankets for displaced families. These were not interruptions but the pulse of its pedagogy: education as survival, adaptation, and defiance. At CSB, resilience is not an abstraction or a tired label, but a daily practice, a pedagogy that refuses paralysis and instead grows new organs and processes in the face of catastrophe.This is education as liberation. Paulo Freire’s critique of the “banking model” of education casts students as passive vessels to be filled. CSB insists on the opposite: that students’ struggles, imaginations, and histories are the raw material of learning itself. bell hooks called this “engaged pedagogy,” an education rooted in the body, community, and political struggle.At CSB, these theories take form. Creation becomes survival. Design becomes dissent. Pedagogy becomes politics.The studio is a crucible of collective practice. Within this environment, students design, cut, drape, and stitch against a backdrop of scarcity, salvaged fabrics, a small number of computers, sputtering generators, and machines that refuse to die. But learning here is not only technical; it is relational and existential. Students collaborate with local artisans, international designers, and industry players, cultivating networks of solidarity rather than competition. This is deliberate. In a country fractured by sectarianism and in a global industry defined by exploitation, CSB wagers that community itself is the curriculum. To learn here is to learn not only how to navigate the industry, but how to make a life with others in a landscape of annihilation.This ethos crystallized in June 2025 with We Have Arrived, We Are Home, CSB’s first graduate fashion show in seven years. Against all odds, with limited funding and a political climate on the brink, the show seemed to materialize from nothing. In truth, it was carried into being by more than one hundred volunteers: students, creatives, teachers, and friends. It was more than a graduate showcase; it was a demonstration of what a community can assemble when the world demands only survival, a collective act of refusal staged as fashion, proof that creativity and solidarity can conjure abundance from ruin.Care and relationship form the other axis of CSB’s pedagogy. Relational theories of education, such as Nel Noddings’ ethics of care and Gert Biesta’s concept of education as encounter, emphasize that teaching and learning unfold in relationship, not in abstraction. CSB embodies this principle in both structure and spirit. Inside, diversity becomes a daily, lived practice: students from different sectarian, socioeconomic, and ethnic backgrounds learn side by side in a shared creative environment. That coexistence is not incidental. The encounter with the “other” becomes part of the curriculum. Externally, the school’s partnerships with like-minded industry movers, artists, artisans, humanitarian organizations, and cultural institutions ground education in real networks of collaboration and interdependence. By engaging directly with these ecosystems, students learn negotiation, context, and care as part of their creative process.This relational ethos extends beyond graduation. Unlike institutions that sever contact once a degree is conferred, CSB maintains a living relationship with its alumni through mentorship, opportunities to teach, shared resources, inclusion in the CSB Boutique, and ongoing collaborations. The result is a cyclical ecosystem where learning and teaching blur, and where each generation sustains the next. The impact of this model is evident in the trajectories of its graduates: alumni who have worked with renowned designers, launched independent brands, opened production houses, and taken on teaching roles across Lebanon and beyond. Many continue to give back directly, mentoring younger students, collaborating on projects, and creating access to networks that were once closed to them. At CSB, education does not end; it circulates. Here, creativity and connection are inseparable, each sustaining and amplifying the other.CSB belongs to a lineage of radical schools. Like Venezuela’s El Sistema, it reframes culture as a weapon of empowerment. Like Black Mountain College in the U.S., it melds art, life, and politics into a single experiment. Yet unlike Black Mountain, which flickered briefly and disappeared, CSB has endured through more than a decade of compounded crises, nurturing a generation of alumni who are reshaping creative industries across the region. They are living proof that access to education, when bound to community and care, can transform not only individual lives but entire cultural landscapes.And while CSB is deeply rooted in Lebanon, its lessons reach beyond it. Across the world, higher education grows ever more exclusionary, strangled by debt, hollowed out by corporate capture, or priced beyond reach. The creative industries mirror these logics, fortified by the same structures of exclusivity and extraction that define neoliberal economies at large. In this context, CSB offers not a romantic exception but a functioning counter-model: proof that education can be free, that pedagogy can be collective, that culture can exist as a commons. It shows that schools can act not as engines of hierarchy but as living organisms, responsive to their times, resistant to the forces that would otherwise dismantle them.In this way, CSB speaks across borders. It resonates with communities in Latin America seeking to decolonize knowledge, with student movements in Europe demanding debt abolition, with grassroots schools in Africa reclaiming cultural practices suppressed by colonial legacies. It offers not only a vocabulary but a living practice for educators, artists, and organizers across the world who are asking how learning can be reclaimed as a collective right rather than a privatized asset.To call CSB a fashion school misses the point. It is a pedagogical insurgency, a living organism that adapts, resists, and regenerates in contexts that would otherwise dictate deprivation. In a world unraveling under capitalism, repression, and collapse, CSB asserts another truth: that futures can still be made, even when everything conspires to erase them."

}

,

"relatedposts": [

{

"title" : "aja monet’s new single: “hollyweird”",

"author" : "aja monet",

"category" : "visual",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/aja-monet-hollyweird-release",

"date" : "2026-02-19 05:00:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/aja-monet---Hollyweird-_-Single-Art.jpg",

"excerpt" : "Surrealist blues poet aja monet shares her first new music since 2023 with the release of her timely new single “hollyweird” via drink sum wtr. The track, produced by monet, Meshell Ndegeocello and Justin Brown, arrives with a bold video directed by B+ and Monet herself, and features Chicago rapper and close collaborator, Vic Mensa.",

"content" : "Surrealist blues poet aja monet shares her first new music since 2023 with the release of her timely new single “hollyweird” via drink sum wtr. The track, produced by monet, Meshell Ndegeocello and Justin Brown, arrives with a bold video directed by B+ and Monet herself, and features Chicago rapper and close collaborator, Vic Mensa.“I wrote ‘hollyweird’ on scraps of found paper, frantically jotting down observations and sentiments of the moment during the Los Angeles fires and its aftermath,” monet explains. “The song is an Afropunkesque ode to frustrations and feelings around our current culture of social isolation and performative solidarity. I wanted to speak to the emptiness of ‘hollyweird’ not as a place but as a way of being where insincerity is normalized. Where social interactions become void in of sincerity and we lose sight of community and connection.”“hollyweird” is the first taste of new music from monet since the release of her debut album, when the poems do what they do, in 2023. The album was released by drink sum wtr to wide critical praise and was nominated at the 66th GRAMMY Awards for Best Spoken Word Poetry Album in 2024. The album marked the arrival of a singular poet and peerless lyricist. On it, monet explored themes of resistance, love, and the inexhaustible quest for joy.monet is bringing her singular live show to New York City’s famed Carnegie Hall Theater. The show will take place at the Zankel Hall on May 20th.Get the track on all digital platforms here"

}

,

{

"title" : "How to Resist “Organized Loneliness”: resisting isolation in the age of digital authoritarianism ",

"author" : "Emma Cieslik",

"category" : "essays",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/how-to-resist-organized-loneliness",

"date" : "2026-02-13 15:11:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/American_protesters_in_front_of_White_House-11.jpg",

"excerpt" : "Over the past year, many of us have encountered, navigated, and processed violence alone on our phones. We watched videos of Renee Nicole Good and Alex Pretti being fatally shot and Liam Conejo Ramos being detained by ICE agents. These photos and videos triggered anger, sadness, and desperation for many (along with frustration that these deaths were the inciting blow against ICE agents that have killed many more people of color this year and last).",

"content" : "Over the past year, many of us have encountered, navigated, and processed violence alone on our phones. We watched videos of Renee Nicole Good and Alex Pretti being fatally shot and Liam Conejo Ramos being detained by ICE agents. These photos and videos triggered anger, sadness, and desperation for many (along with frustration that these deaths were the inciting blow against ICE agents that have killed many more people of color this year and last).While the institutions and people committing these crimes do not want them recorded, the Department of Homeland Security and the wider Trump administration is using “organized loneliness,” a totalitarian tool that seeks to distort peoples’ perception of reality. Although seemingly a symptom of COVID-19 pandemic isolation and living in a more social media focused world, “organized loneliness” is being weaponized to change the way people not only engage with violence but respond to it online, simultaneously desensitizing us to bodily trauma and escalating radicalization and recruitment online.Back in 2022, philosopher Samantha Rose Hill argued that the loneliness epidemic sparked by the COVID-19 pandemic could and would have dangerous consequences. She specifically cites Hannah Arendt’s 1951 book The Origins of Totalitarianism, which argued that authoritarian leaders like Hitler and Stalin weaponized people’s loneliness to exert control over them. Arendt was a Jewish woman who barely escaped Nazi Germany.As Hill told Steve Paulson for “To The Best Of Our Knowledge,” “the organized loneliness that underlies totalitarian movements destroys people’s relationship to reality. Their political propaganda makes it difficult for people to trust their own opinions and perceptions of reality.” Because as Arendt wrote, “the ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction and the distinction between true and false no longer exist.”But there are ways in which we can resist the threat that “organized loneliness” represents, especially in the age of social media. They include acknowledging this campaign of loneliness, taking proactive steps when engaging with others online, and fostering relationships with friends and our communities to stand in solidarity amidst the rise of fascism.1. The first step is accepting that loneliness affects everyone and can be exploited by authoritarian movements.Many of us know this intimately. Back in 2023, the U.S. Surgeon General flagged an already dire loneliness epidemic, that in combination with a transition of most interaction onto social media, changes the way in which we engage with violence and tragedy online. But it can be hard to admit that loneliness affects us, especially when we are constantly connected through social media. It’s important to admit that even for the most digitally literate and active among us, “organized loneliness” not only can occur but especially occurs on social media.Being susceptible to or affected by “organized loneliness” is not a moral shortcoming or a personal failure but acknowledging it and taking steps to connect with one another is the one way we resist totalitarian regimes.2. Next, take social media breaks–and avoid doomscrooling.Even before the advent of social media or online news outlets, Arendt was warning about how loneliness can become a breeding ground for downward spirals. She explains that the constant consumption of tragic, violent, and deeply upsetting news–and watching it unfold in front of us can not only be overstimulating but can desensitize us and disconnect us from reality.While it can be difficult when most of our social lives exist on social media (this will be unpacked later), experts recommend that people limit using social media to less than two hours per day and avoid using it during the first hour after waking up and the last hour before going to sleep. People can use apps that limit overall screen time or restrict access to social media at set times–the best being Opal, One Sec, Forest, and StayFree. People can also use these apps to limit access to specific websites that might include triggering news.But it’s important to recognize that avoiding doomscrooling does not give people license not to stay informed or to look away from atrocities that are not affecting their communities.3. Resist social media echo-chambers by diversifying your algorithm.When you are on social media, however, it’s important to recognize that AI-based algorithms track what we engage with and show us similar content. People can use a VPN to search without creating a record that AI can track and thus offer us like offerings, but while the most pronounced (and reported on) examples focus on White, cis straight men and the Manoverse, echochambers can affect all of us and shift our perception of publicly shared beliefs.People can resist echo-chambers by seeking out new sources and accounts that offer different, fact-based perspectives but also acknowledge their commitment to resisting fascism, such as Ground News, ProPublica, and Truthout. Another idea is to follow anti-fascist online educators like Saffana Monajed who promote and share lessons for media literacy. People can also do this by cultivating their intellectual humility, or the recognition that your awareness has limits based largely on your own experiences and privileges and your beliefs could be wrong. Fearless Culture Design has some great tips.While encountering and engaging different perspectives is vital to resisting echochambers and social algorithms, this is not an invitation to follow or platform any news outlet, content creator, or commentator that denies your or other people’s personhood.4. Cultivate your friendships and make new ones.In a time when many of us only stay in contact with friends through social media, friendships are more important than ever. Try, if you can, to engage friends outside of social media–whether it’s through in-person meet ups (dinners, parties, game nights) or on digital platforms that are not social media-based, for example coordinating meet-ups over Zoom or Skype. This can be a virtual D&D campaign, craft circle, or a virtual book club. While these may seem like silly events throughout the week, they help build real connection.It’s important to connect with people outside of a space that uses an algorithm to design content and to reinforce that people are three-dimensional (not just a two-dimensional representation of a social media profile). There are even some apps that assist with this goal, such as Connect, a web app designed by MIT graduate students Mohammad Ghassemi and Tuka Al Hanai to bring students from diverse backgrounds together for lunch conversations.Arendt writes that totalitarian domination destroys not only political life but also private life as well. Cultivating friendships–and relationships of solidarity with your neighbors and fellow community members–are the ways in which we not only resist the destruction of private relationships but also reinforce that we and others belong in our communities–and that we can achieve great things when we stand together!5. With this in mind, practice intentional solidarity with one another.While it’s likely no surprise, fascism functions to both establish a nationalist identity that breeds extremism and destroy unification and rebellion against authority. The best way to resist the isolation that totalitarian governments breed is to practice intentional acts of solidarity with marginalized communities, especially communities facing systemic violence at the hands of an authoritarian power.Writer and advocate Deepa Iyer discusses the importance of action-based solidarity in her program Solidarity Is, part of the Building Movement Project, and Solidarity Is This Podcast (co-hosted with Adaku Utah) discusses and models a solidarity journey that foregrounds marginalized communities. I highly recommend reading her Solidarity Is Practice Guide and the Solidarity Syllabus, a blog series that Iyer just started this month to highlight lessons, resources, and ideas of how to cultivate solidarity within your own communities.6. Consume locally and ethically, and reject capitalist productivity.And one way that people can stand in solidarity with their communities is to support local small businesses that invest back into the communities. When totalitarianism strips people of many platforms to voice concern, one of the last remaining power people have is how and where they spend their money. Often, this is what draws the most attention and impact, so it’s important to buy (and sell) based on Iyer’s Solidarity Stances and to also resist the ways in which productivity culture not only disempowers community but devalues human labor.At the heart of Arendt’s criticism of totalitarian domination is the ways in which capitalism, a “tyranny over ‘laborers,’” contributes to loneliness itself (pg. 476). Whether intentional or not, this connects to modern campaigns not only of malicious compliance but also purposeful obstinance in which people refuse to labor for a fascist regime but to mobilize their ability to labor as a form of resistance–thinking about the recent walkouts and boycotts that resist by weaponizing our labor and our spending power.Not only should people resist the conflation of a person’s value to their productivity, but they should use their labor–and the economic products of it–as tools of resistance in capitalism.Thankfully as Arendy writes, “totalitarian domination, like tyranny, bears the germs of its own destruction,” so totalitarianism by definition cannot succeed just as humans cannot thrive under the pressure of “organized loneliness.” For this reason, it’s a challenge to hold on and resist the administration using disconnection to garner support for the dehumanization of and violence against human beings. But as long as we do, we have the most powerful tools of resistance–awareness, friendship, community, and solidarity–at our disposal to undo totalitarianism just as it was undone back in the 1940s."

}

,

{

"title" : "A Trail of Soap",

"author" : "susan abulhawa, Diana Islayih",

"category" : "excerpts",

"url" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/readings/a-trail-of-soap",

"date" : "2026-02-13 08:40:00 -0500",

"img" : "https://everythingispolitical.com/uploads/Trail_of_Soap.png",

"excerpt" : "From EVERY MOMENT IS A LIFE compiled by susan abulhawa. Copyright © 2026 by Palestine Writes. Reprinted by permission of One Signal Publishers/Atria Books, an Imprint of Simon Schuster, LLC.",

"content" : "From EVERY MOMENT IS A LIFE compiled by susan abulhawa. Copyright © 2026 by Palestine Writes. Reprinted by permission of One Signal Publishers/Atria Books, an Imprint of Simon Schuster, LLC.Illustration by Rama DuwajiI met Diana Islayih at a series of writing workshops I conducted in Gaza between February and May 2024. She was one of a couple dozen young people who traveled for hours on foot, by donkey cart, or in cars forced to crawl through the crush of displacement. They were all trying to survive an ongoing genocide. Still, they risked Israeli drones and bombs to be there, just to feel human for a few hours, like they belong in this world, to touch the lives they believed they might still have.Soft-spoken and slight, Diana was the only one who recognized me, asking quietly if I was “the real susan abulhawa.” Each writer progressed their piece at their own pace, and would read their work aloud in the workshops to receive group feedback. Diana’s was the only story that emerged almost fully formed, as if it had been waiting for language. She teared up the first time she read it aloud, and again, the second.By the third reading, the tears were gone. “I got used to the indignities,” she told me. “Now I’m used to reading them out loud.” She confessed that she struggled living “a life that doesn’t resemble me.” On our last day together, I reminded her of what she’d said. She smiled ironically. “Now I don’t know if I resemble life,” she said.What follows is Diana’s story, written from inside that unrecognizable life, bearing witness not through spectacle, but through one intimate moment in the unbearable weight of the everyday. — susan abulhawa, editor of Every Moment Is a Life, of which this essay is part.Courtesy of Simon & SchusterI poured yellow liquid dish soap into my left palm, which instinctively cupped into a deep hollow, like a well yearning to be a well once more. I would need to wash my hands after using the toilet near our tent, though the faucet was usually empty. Water had been annihilated alongside people in this genocide, becoming a ghost that graciously deigns to appear to us when it wishes to—one we chase after rather than flee.The miserable toilet was made of four wooden posts, wrapped in a makeshift curtain made from an old scrap of fabric—so sheer you could see silhouettes behind it. A blanket full of holes and splinters served as a “door.”Inside, a concrete slab with a hole in the middle. You need time to convince yourself to enter such a place. The stench alone seizes your eyelids and turns your stomach the moment it creeps into your nose.I thought about going to the damned, distant women’s public toilet. I hated it during the first weeks of our displacement, but it was the only one in the area where you could both relieve yourself and scrub off the dust of misery that clung to every air molecule.It infuriated me that it was wretched and run-down, and the crowding only made it worse—full of sand, soiled toilet paper, and sanitary pads scattered in every corner.“Should I go?” I asked myself, aloud.I decided to go, taking one step forward and two steps back. I’d ask anyone returning from the toilet, “Is there water in the tap today?” and await the answer with the eagerness of a child hoping for candy.“You have to hurry before it runs out!”Or, more often, “There isn’t any.”So we’d all—men, women, and children—arm ourselves with a plastic water bottle, which was a kind of public declaration: “We’re off to the toilet.” We’d also carry a bar of soap in a box, although most people didn’t bother using it since it didn’t lather and was like washing your hands with a rock.I looked up and exhaled, staring into the vast gray nothingness that stared right back at me. Then I stepped out onto the sand across from our ramshackle displacement camp—Karama, “Camp Dignity”—though dignity itself cries out in this filthy, exhausted place, choked with chaos and a desperate scramble to moisten our veins with a drop of life.The road was empty, as it was early morning, and even the clamor of camp life lay dormant at that hour. Still, I couldn’t relax my shoulders—to signal my senses that we were alone, that we were safe. My fingers remained clenched over the yellow dish soap, my hand hanging at my side to keep it from spilling.I crossed the distance to the toilet—step by step, meter by meter, tent by tent. The souls who dwelled in them, just as they were, unchanged, their curious eyes fixed on me. I passed a garbage heap, shaped like a crescent moon, overflowing with all kinds of empty food cans—food that had ruined the linings of our intestines and united us in the agonies of digestion and bowel movements.Something trickled from my palm—a thread of liquid that felt like blood dripping between my fingers, down my wrist in thickening droplets. My hand trembled, and my eyes blurred. I convinced myself—without looking—that it was all in my head, not in my hand, quickened my pace, my heartbeat thudding in my ears.At last, I reached the only two public toilets in the area, one for men and the other for women, both encased in white plastic printed with the blue UNICEF logo.Inside, I was met with the “toilet chronicles”—no less squalid than the toilet itself—unparalleled chatter among women who’d waited long hours in the line together.The old women bemoaned the soft nature of our generation, insisting our condition was a “moral consequence” of our being spoiled.Other women pleaded to be let into the toilet quickly because they were diabetic. They banged on the door with urgency and physical pain, like they would break in and grab the person behind it by the throat, shouting, “When will you come out?!”The woman inside yelled back, “I’m squeezing my guts out! Should I vomit them up too? Have patience! Damn whoever called this a ‘rest room’!”I looked around. A pale-faced woman smiled at me. I returned her smile, but my face quickly stiffened again, as if the muscles scolded me for stretching them into a smile. A voice inside me whispered meanly, What are you both even smiling about?A furious cry rang from the other stall, “Oh my God! Someone is plucking her body hair! What are you doing, you bitch? It’s a toilet! A toilet!”Another voice shot back, “Lower your voice, woman, and hurry up! The child’s crying!”Two little girls stood nearby, with tousled hair, drool marking their cheeks, their eyes half shut. They were crying to use the toilet, clutching their crotches, shifting restlessly in the sandy corridor where we stood.I was trying to push through to the water tap at the end of the hall, attempting to escape this tiresome, tragic theater. As my luck would have it, there was no water. I opened my palm. It too was empty. The yellow dish soap my mother bought yesterday was gone. All that remained was a sticky smear across my left hand and a long thread trailing behind me in the sand. Had it been dripping from my hand all along the way?I twisted the faucet handle back and forth—a futile hope for even a thin thread of water. Not a single drop came.My body sagged under the weight of rage, disappointment, fury, and a storm of unanswerable questions. I rushed through the crowded corridor of angry women, out into the street. I couldn’t hold back tears.I wept, cursing myself and the occupation and Gaza and her sea— the sea I love with a weary, lonely love, just as I’ve always loved everything in this patch of earth.I sobbed the entire way back. Without shame. I didn’t care who saw—not the passersby, not the homes or tents, not the ground I walked on. My grief rained tears on this land on my way there and back.But the land’s thirst is never quenched—neither with our tears, nor with our blood.My eyes were wrung dry from crying by the time I reached our tent. I collapsed on the ground, questions clamoring in my head.Can a homeland also be exile?Can another exile exist within exile?What is home?Is home the homeland itself, the soil of a nation?Or is it the other way around—the homeland is only so if it’s truly home?If the homeland is the home, why do I feel like a stranger in Rafah—a place just ten minutes from my city, Khan Younis?And why did I fear the feeling I had when I imagined myself in our kitchen, where my mother cooked mulukhiya and maqluba for the first time in six months, even though I wasn’t at home—in our house?That day, I said aloud, “Is this what the occupation wants? For me to feel ‘at home’ merely in the memory of home?”How can I feel at home without being there?How can I be outside of my homeland when I’m in it?I looked down at my hand—dry and cracked with January’s chill. The yellow soap liquid had turned into frozen white powder between my fingers."

}

]

}