What do Sheenkhālåi and Shaokhālåi mean? And how do these dualities play into your broader work?

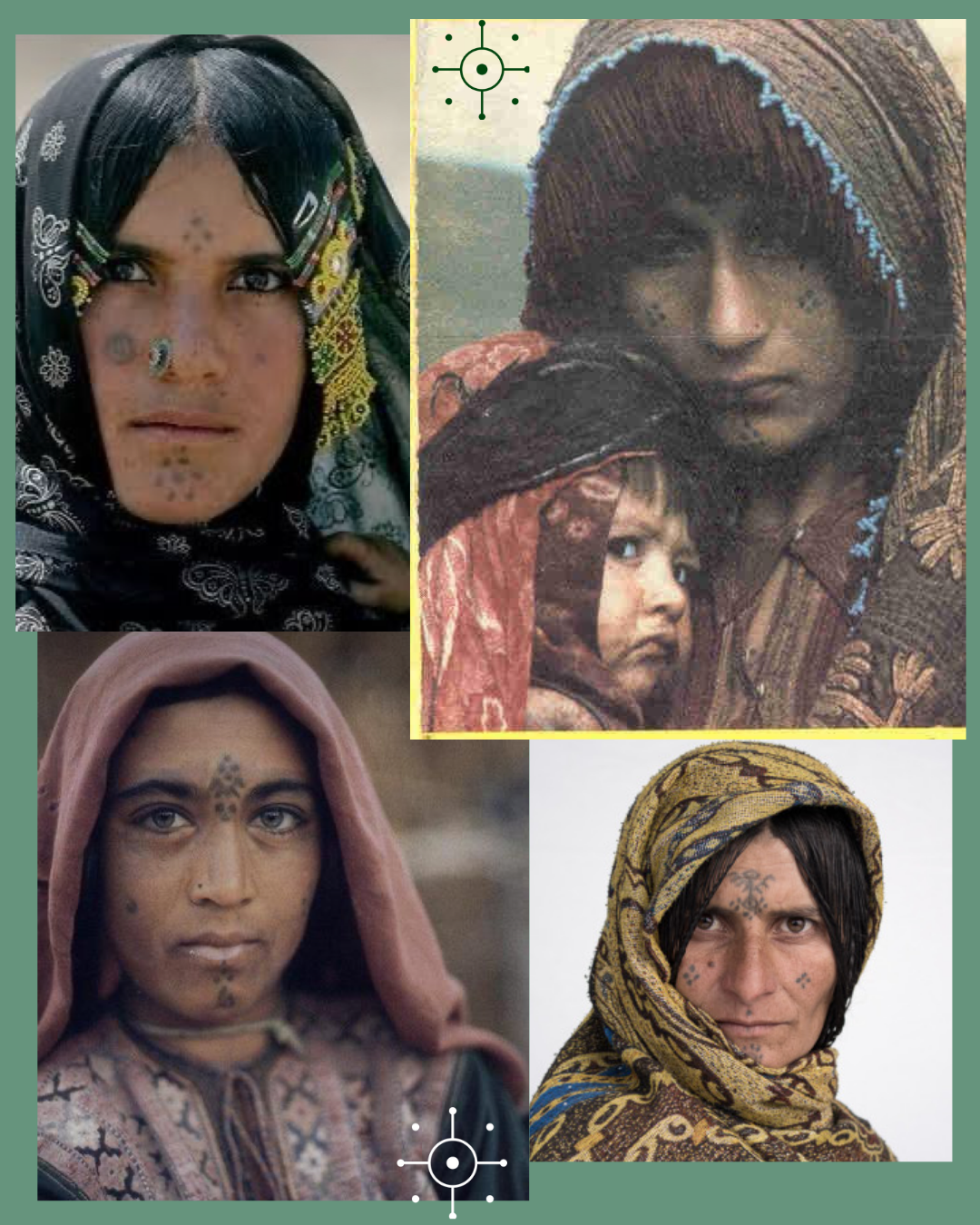

Sheen means green, and khaal means dot in Pashto. When used together, the word refers to the traditional tattoos of Afghanistan, usually done on the face. Sheenkhālåi is the Pashto word for women with these tattoos. Shao is the Dari, specifically Kabul slang, for night. Shaokhālåi is a play on the Pashto words, used for women donning my temporary tattoos, “for one night,” based on the sheenkhaal tradition.

What inspired you to create Sheenkhālåi / Shaokhālåi, and how did you first encounter the tattoo traditions of Afghan women?

Women all over Afghanistan have these markings, so it was something I saw growing up in Kabul, as well as in the provinces. Members of my family have them as well. I didn’t want to receive my markings until later in life, so as a teen I had this idea that instead of drawing on eyeliner, like most girls do, I’d create temporary tattoos that would stay on for some time, in the different motifs and designs sheenkhaal is traditionally done.

What inspired you to revive this tradition?

I don’t know if I am reviving quite as much as celebrating.

In your reinterpretation, these tattoos become more than body art—they’re protest, memory, identity. How do you see them functioning as a feminist or anti-colonial act?

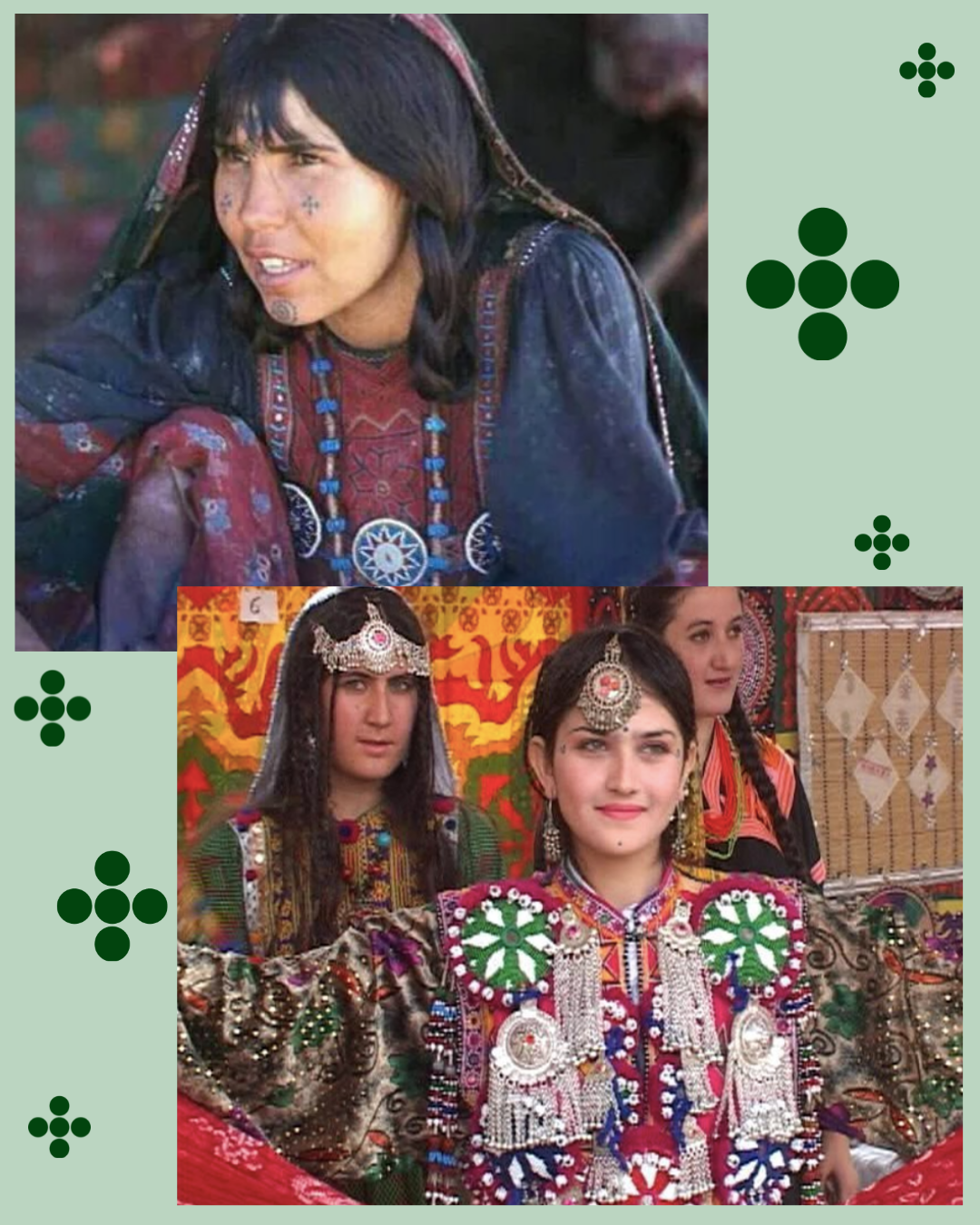

Unfortunately, in Afghanistan, these markings are often seen as “low class” and not something the educated elite participates in. Blingistan, my jewelry and clothing line, as well as my other visual art endeavors, seek to celebrate the working class of Afghanistan, the revolutionary aspects, and the truth of our culture and identity. The past 20 years, with the NATO invasion, and now with the Taliban, the world only sees a one-dimensional side to Afghanistan, especially Afghan women, so much so that we Afghans have started believing these narratives about ourselves. We aren’t fodder for international tragedy porn; we are punk, badass, revolutionary people, with a zest for life and a very, very colorful culture. And I’m after celebrating that.

How does this work interact with your other projects, like Blingistan or your painting/installation work, when it comes to reclaiming cultural narratives?

Well now I have a new accessory I wear every day! I don’t want us to feel that the only way to be an Afghan artist is to create art that the West will lap up, because that is the only way to be successful or get funding because that’s a very skewed and distorted version of the reality of our phenomenal country. We don’t have to sell out our people and culture, nor do we have to lie about ourselves. I make art, whether paintings, jewelry, or these tattoos, for my people. Afghans are my audience first and foremost.

How do you define this work as being political?

Celebrating the working class and shunning the elite is inherently political.

How do you define your work’s relationship with Nature?

The process of the traditional sheenkhaal is very tied to nature. We take the blood of the shaothal plant and mix it with our own during specific phases of our life cycle. The designs themselves celebrate Mother Nature, sometimes tattooed in the shape of plants, animals, and stars. This is an old tradition, older than Abrahamic religions, from our pagan roots. We as a people still hold that connection to Mother Nature; we derive our strength from her and respect her dearly. I’d say this played a role in why no colonizers, 500 or 5 years ago, have been able to erase our culture and identity, no matter how much they tried.