This year’s Met Gala theme, “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style” could pass for a late tribute or a slick PR stunt, but it’s got way sharper claws: it’s a full-on provocation. We’re living in a time where Black stars dazzle on red carpets but get sidelined in boardrooms, classrooms, and courtrooms. In this climate, hyping the Black dandy is a sly rebellion. It thrusts a figure into the spotlight who’s always been political, always strategic, and always dressed to slay not just with swagger, but with razor-sharp intent.

Let’s keep it 100: Black dandyism isn’t just about serving looks. It’s about serving looks when the world said you had no right to. When society labeled you chaotic, threatening, or invisible, and you stepped out in a suit so crisp it could carve through bias. As DEI gets dismantled and Black studies programs vanish from campuses, the Met Gala’s theme hits less like a festivity and more like a stylish counterpunch.

So, what’s the deal with a Black dandy?

The word “dandy” usually conjures prissy white men from 19th-century Europe, think Oscar Wilde in lush velvet or aristocrats in wigs and buckled kicks. But Black dandyism? It flips that whole aesthetic on its head. It’s not about chasing white refinement; it’s about torching it. It’s wielding style to claim your humanity in a system built to snatch it away.

Scholar Monica L. Miller literally wrote the book on it, “Slaves to Fashion” maps out how Black men across the diaspora used elegance as resistance, turning the dandy from a Eurocentric trope into a global tool of survival and spectacle. The book serves as an inspiration for this year’s theme with Miller guest curating the Met’s exhibition.

Take Frederick Douglass, the ultimate image maestro. One of the most photographed men of his era, every portrait, hand on lapel, lion’s mane, fierce gaze, was a study in defiance. He didn’t just dress well; he crafted a persona that screamed, “I’m not your stereotype. I’m your equal.” In a media world drowning in blackface and minstrel mockery, Douglass turned the camera into a weapon, armed with a tailored suit and an unbreakable stare.

This vibe, Black men dressing to disrupt, carried through the 19th and 20th centuries. In the Caribbean, newly freed men rocked European-style suits to flex their liberty. In South Africa, young Black men called “tsotsis” used tailoring as rebellion and a ladder up, even under apartheid’s weight.

As Monica Miller argues in “Slaves to Fashion”, these weren’t just style choices, they were political blueprints, passed through generations and across continents.

And then came the Sapeurs of the Congo.

The Sapeurs: Style as Post-Colonial Flex

The “Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes” (Society of Ambiance-Makers and Elegant People), aka Sapeurs, kicked off in the 1920s and went wild in the 1960s post-independence era. These Congolese men strutted through Kinshasa and Brazzaville in vibrant, impeccably tailored European suits, often dropping more on clothes than rent. This wasn’t mere vanity, it was sartorial warfare. In a post-colonial world still haunted by European superiority, Sapeurs dressed like Parisian kings, not to blend in, but to outshine.

They turned colonial dress codes into a bold performance, using designer labels to mock and mimic the elite. Sapeurism wasn’t just a look; it was a manifesto that self-worth could rise through elegance, even in empire’s ashes.

Their influence still ripples through global menswear and Black diasporic fashion. Pharrell rocked Sapeur-inspired fits in his “Something in the Water” visuals. Solange gave them a nod in “Losing You”. And now, the Met’s finally catching the wave.

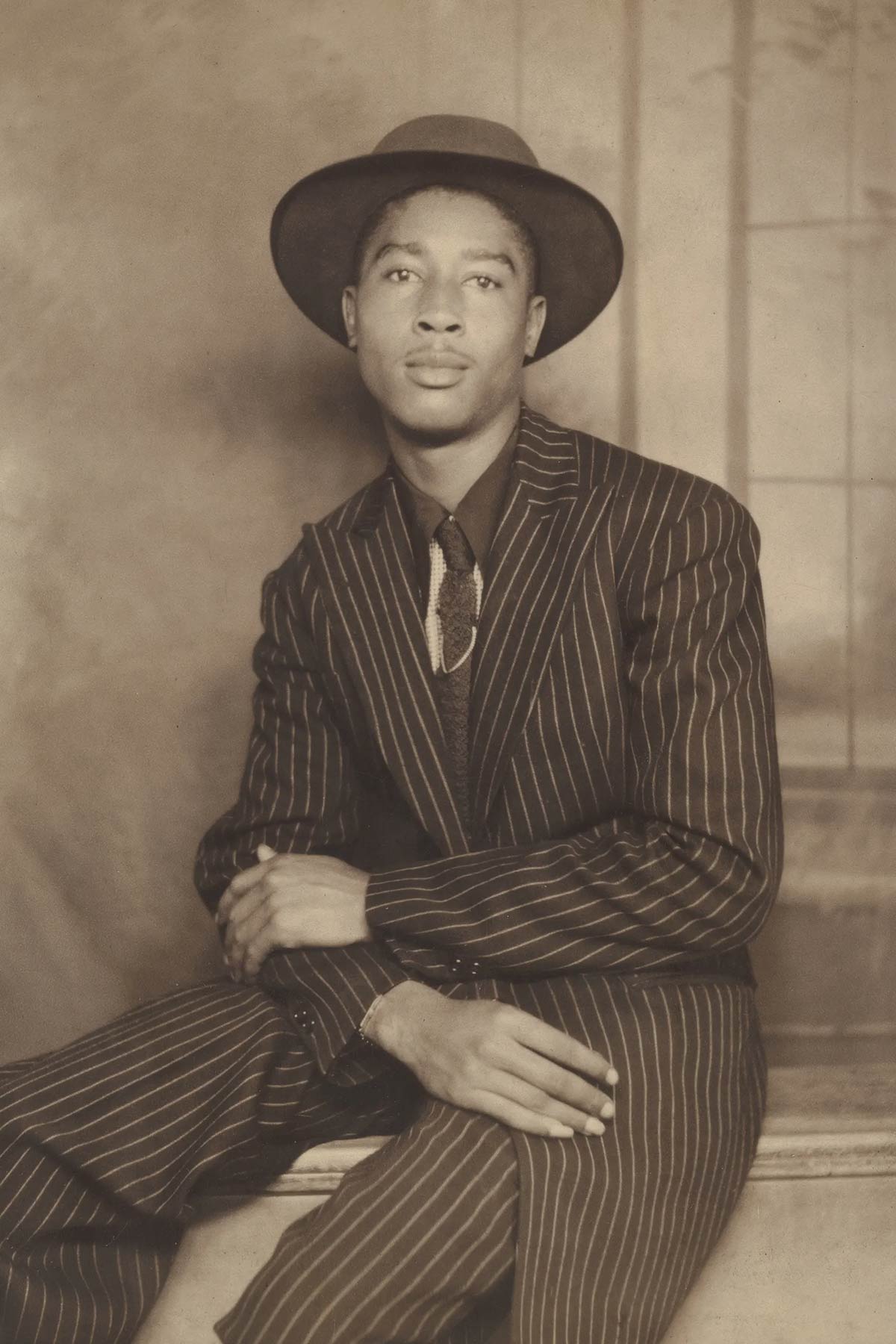

The Harlem Renaissance: Style as Intellectual Swag

In the 1920s and ’30s, Harlem wasn’t just a cultural hotspot, it was a fashion mecca. Black artists, poets, and thinkers knew style was power. Cue the Harlem dandy.

Men like Alain Locke, the first Black Rhodes Scholar and Harlem Renaissance trailblazer, dressed with Oxford-level polish. His style was an extension of his politics, smashing stereotypes of the “Negro intellectual” as primitive or pitiable. Even Langston Hughes, more poet than posh, got the memo. “I wear my gold watch and fob,” he wrote, “and I am proud of that.”

Harlem dandies weren’t just rocking white fashion, they were remixing it, blending Savile Row cuts with African American jazz energy to craft something modern, urban, and unapologetically Black. That energy echoes forward in Dapper Dan’s Gucci-covered Harlem atelier, where logomania meets legacy, and in Beyoncé’s Black Is King, a 21st-century tribute to diasporic elegance that channels Harlem Renaissance glam, Zulu regality, and couture-level pageantry into one glittering sermon.

And it wasn’t just the guys. Women like Zora Neale Hurston and Josephine Baker weaponized style, using fringe, furs, and feathers to defy racial and gender norms. Baker, especially, used her image to rule 1920s Paris, a city that fetishized her even as she bent it to her will.

Civil Rights to Soul Power

By the 1960s and ’70s, Black style went from mimicry to mastery. Picture Malcolm X in his trench coat and glasses, every inch the revolutionary scholar. James Baldwin in turtlenecks and tailored suits, daring you to dismiss him. Stokely Carmichael in a Nehru jacket, channeling Pan-African vibes while preaching Black Power.

Even as Afrocentrism and “Black is Beautiful” took off, the dandy aesthetic didn’t fade, it leveled up. You saw it in Sammy Davis Jr., blurring showman and activist, or Marvin Gaye, whose velvet blazers and silk shirts mixed sensuality with gravitas.

Dandyism wasn’t just a jab at white supremacy anymore; it was a full-blown cultural identity.

The Hip-Hop Era

In the ’80s and ’90s, Black style split and soared. Hip-hop brought baggy jeans, Timberlands, and oversized everything, but the dandy lane stayed open. Think André 3000 in ruffled shirts and suspenders or Biggie Smalls in Coogi and Versace.

This mix of street and suit, rebellion and luxury, still fuels modern Black style. Today, we’re in a dandy renaissance, led by icons like the late André Leon Talley, who spun his Black Southern roots into high-fashion wizardry, owning front rows with fur and flair. Colman Domingo, this year’s Met Gala co-chair, whose bold tuxedos and jewel-toned suits turn red carpets into Black Broadway. LeBron James, whose NBA tunnel walks are runway-level flexes of tailoring and culture. Billy Porter, queering the dandy game with tuxedos-meet-tulle, smashing every gender norm. And now the Met Gala, the place where fashion’s biggest circus meets its richest donors, is finally giving the dandy his due.

Why This Theme Hits Different Now

“Superfine: Tailoring Black Style” drops in 2025, a year of political chaos. Trump’s comeback is real and terrifying. DEI programs are getting shredded. Companies that posted black squares in 2020 are ghosting their diversity vows. The culture war rages on.

So, the Met Gala, a night dripping in privilege and performative allyship, celebrating Black dandyism right now? That’s almost revolutionary. Almost.

This theme’s a sneaky beast. It’s about tailoring, sure, but also history, resistance, and refusing to shrink. It’s about claiming beauty as a right and a weapon.

It’s also about the labor, the Black tailors, seamstresses, stylists, and designers, often nameless, whose craft made others shine while they stayed in the shadows.

The Risk

Of course, there’s danger here. The Met Gala has a habit of aestheticizing without understanding. Of flattening history into looks. We’ve seen it before religious iconography turned into fashion cosplay, punk neutered into couture. And now, the dandy risks becoming just another “inspiration.”

I can already see it: white celebs in zoot suits calling it “homage.” Fast fashion brands throwing kente cloth on everything “diasporic.” TikTokers thinking Sapeur’s a fragrance line.

But I can also dream big.

A gallery of Baldwin’s suits, Baker’s feathers, Talley’s capes. Red carpet looks pulling from Caribbean tailoring, South African street vibes, HBCU homecoming energy, and Harlem ballroom fire. A moment where Black beauty isn’t an afterthought, it’s the whole show.

Black Dandyism Still Snaps

What we wear is never just fabric. For Black folks, getting dressed has always been more than vanity it’s survival, defiance, and joy. In 2025’s messy political climate, that message hits like a thunderclap.

So let this Met Gala be a slay-fest, but also a reckoning. A shout-out to the tailors, the dandies, the disruptors. The ones who stitched rebellion into every seam. The ones who refused to be erased, demanding style and substance. The ones who showed the world:

We’ve always been superfine.